The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

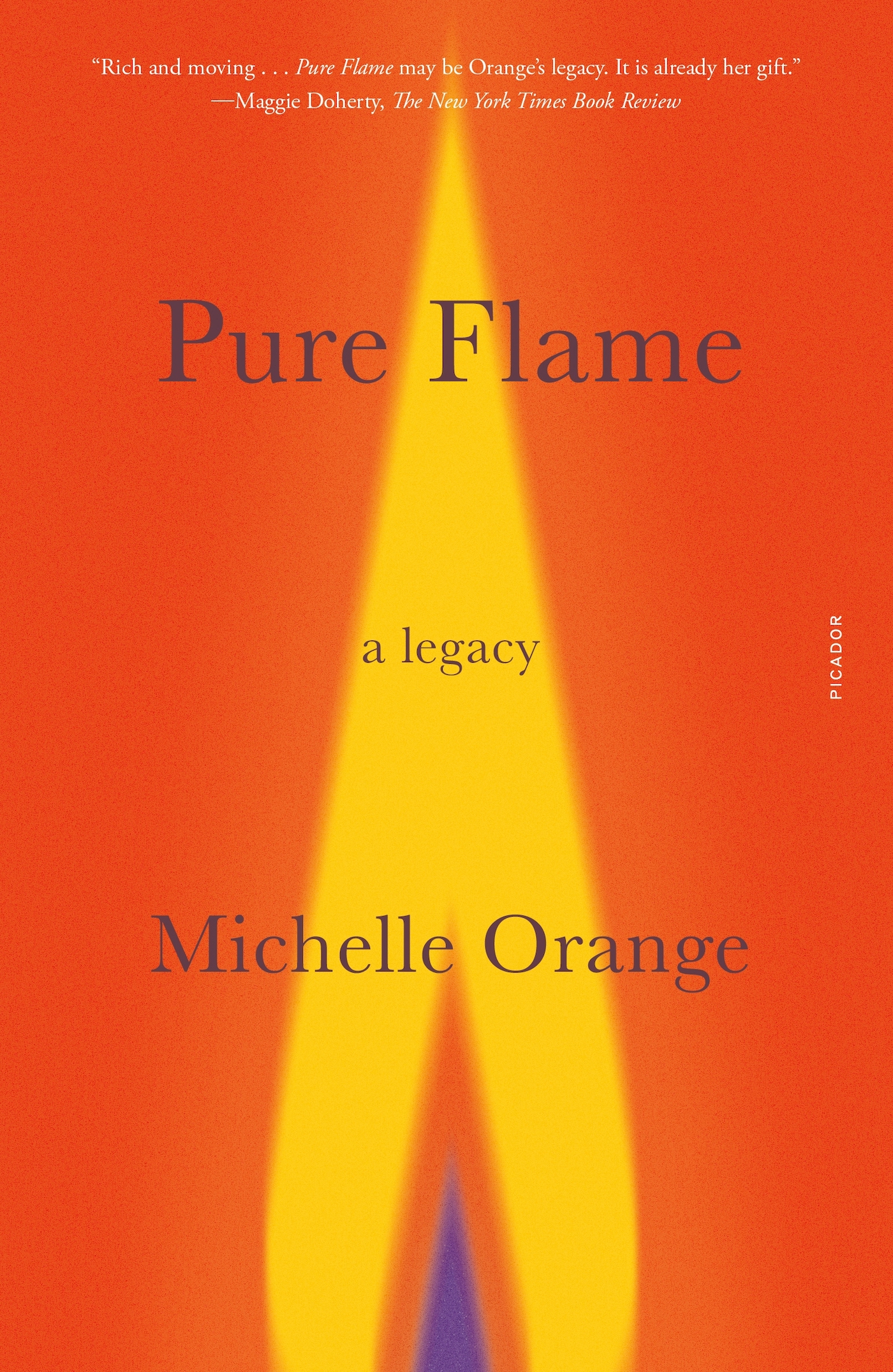

Indeed I did not think of myself as a woman first of all I wanted to be pure flame.

DURING ONE OF THE TEXTING SESSIONS that became our habit over the period I now think of as both late and early in our relationship, my mother revealed the existence of someone named Janis Jerome. The context of our exchange was my need for context: two years earlier I had set out to capture the terms of our estrangement, to build a frame so fierce and broad it might finally hold us both.

If not an opponent to the cause, my mother was a wily associateallied in theory but elusive by nature, inclined to defy my or any immuring scheme. The channel that opened between us across her sixties and my thirties spanned two countries and bypassed decades of stalled communication. We pinged and texted our way into daily contact, a viable frequency. This was its own miracle, a combined feat of time, technology, and pent-up need. As she neared seventy, the repeated veering of our habitually light, patter-driven exchanges into fraught, personal territory was my doing, a response to a new and unnameable threat. Perhaps she had felt it too: that there may not be time to know all the people I had been in her absence; that I might never meet the many versions of her I had discounted or failed to recognize. That we wouldnt tell the most important stories.

If our withholding was mutual, it was part of a tradition I took from her, and she from her mother. I sought a context for this too, the narrative affliction so common to maternal lines and so little changed by a century of marked progress. If anything, the supposed release from pastlessness and isolation that kept a woman from imagining herself as universalworthy of story and its ritual transmissionhad further troubled a primary bond. Mother-daughter relationships are generally catastrophic, Simone de Beauvoir once observed. This we knew; this everyone knows. It has been understood too that the general catastrophe of mother-daughter relationships makes them less and not more interesting, unfit for inscription.

As much as anyone, I have manifested this view. For the better part of my life, only contemplating our relationship interested me less than contemplation of my mother. As a writer the subject appeared fatal. Our catastrophe represented an absence of imagination and vitality; it was where story went to die. By the time my mother introduced me to Janis Jerome, however, early in 2016, something had shifted. Unbeknownst to her, I had spent the previous two years struggling to articulate the terms of a new projectabout legacy, feminism, and failure, questions I sought to examine and refract through the prism of mother-daughter relations. In my half conception of it, the project would rest in the shadow of my mothers mortality, colored and inflected as I saw fit by the vague, theoretical specter of her loss. It would deploy specific elements of her lifeour livesto larger, abstract ends. As a matter of inability as much as instinct, it would privilege argument over plot, ideas over narrative, something else over straight memoir. When an editor asked that summer why I wanted to write such a book, I made a comment about it being the hardest thing I could do at that moment, like I had any idea.

Past seventy when she shrugged off mother-daughter affairs, Beauvoir refused to identify as a feminist for most of her life. As a product of similar if not the same confusions, I have found comfort in this. I see a heritage in it, however twisted, and heritage is what I seek. I had not turned to my mother for such things; she seemed to prefer it that way. Like her, I learned by example and lack of example not to look to the women closest to me for a sense of who and how to be, what was possible in life. Unlike her, I had a mother who had lived out a neoclassical epic of self-determination: 1970s housewife turned MBA turned CEO. Still, her example proved dim, her transformations hidden, their terms boggled. This appeared to me by design: the breach between us had not been a cost of her emancipation but its requirement. As a child I stopped seeing her clearly; in adolescence I stopped wanting to. I charged forth into an old and new kind of catastrophe: despite a near-complete failure to know my mother, my own becoming was both guided and thwarted by a determined effort not to become her.

Standing on the far side of that calamity, I began coaxing our relationship toward disclosure, background, dimensiona shared line of analysis. It was my habit and my handicap: inquiry as an act of love. If she saw it that way, my mother remained a slippery subject, too cool-minded and wildly individual to suffer grand unifying theories, or to share space with the dominant social movement of her time. I respected her resistance even as I weighed its consequence. Early in this process, her lack of interest in feminism interested me most: What was more feminist, I thought, than the purity of its confusion? I found her attitude perverse but not unfamiliar. I had sent at least one of my selves into the shadow sisterhood made up of women who learn to live for themselves, pretending a discrete existence, hoarding their petty freedoms.

I may have met my mother in that lonely place. I would not have known.

MY MOTHER MENTIONED Janis Jerome as though I might recognize the name. She had popped up that early spring eveningtexting, per usualwith questions about that days class, my puking dog, Mercy, and an outstanding payment for one of the contract gigs I used to slap together a living. When I complained, again, about the missing money, she urged me, again, to follow up, keep on it. She took a reliable interest in career and financial concerns, but I recognized her advice as an act of mothering by the way it reached one arm back toward the woman who had had to figure these things out for herself. Be persistent until you understand whats happening, she went on.

When I started at Canada Trust almost 40 years ago, they were underpaying me

I pointed it out and my boss accused me of thinking only about money

Can you imagine

It was their mistake!!!!!

It made me furious

So wrong

How did you figure out they were underpaying you?

I did the math

My salary was supposed to be 10,500 and they were basing deductions on 10,000

I had the letter!

1977

But I was made to feel small for asking

Right

Its a thing with me

IN THE BEGINNING, they made her a clown. They had her bake cakes. At thirty-three, with a six-year-old and a toddler at home, she had answered an ad in the local Pennysaver: assistant coordinator of branch promotions for a national trust company that functioned as a bank. The job was her entry into full-time work. On Saturday mornings she would blow balloons and hang streamers while standing on check-signing podiums. She orchestrated birthday parties for branches opening around the city. She baked sheet cakes in our kitchen, wrapping nickels in foil and dropping them in batter-filled pans. Sometimes the cake paid a penny per slice. She would dress in a clown costume: rainbow wig, painted face, floppy shoes. The idea, I suppose, was to make customers feel at home, to promote the bank as another member of the family, with occasions to celebrate and a mother willing to make a fool of herself.