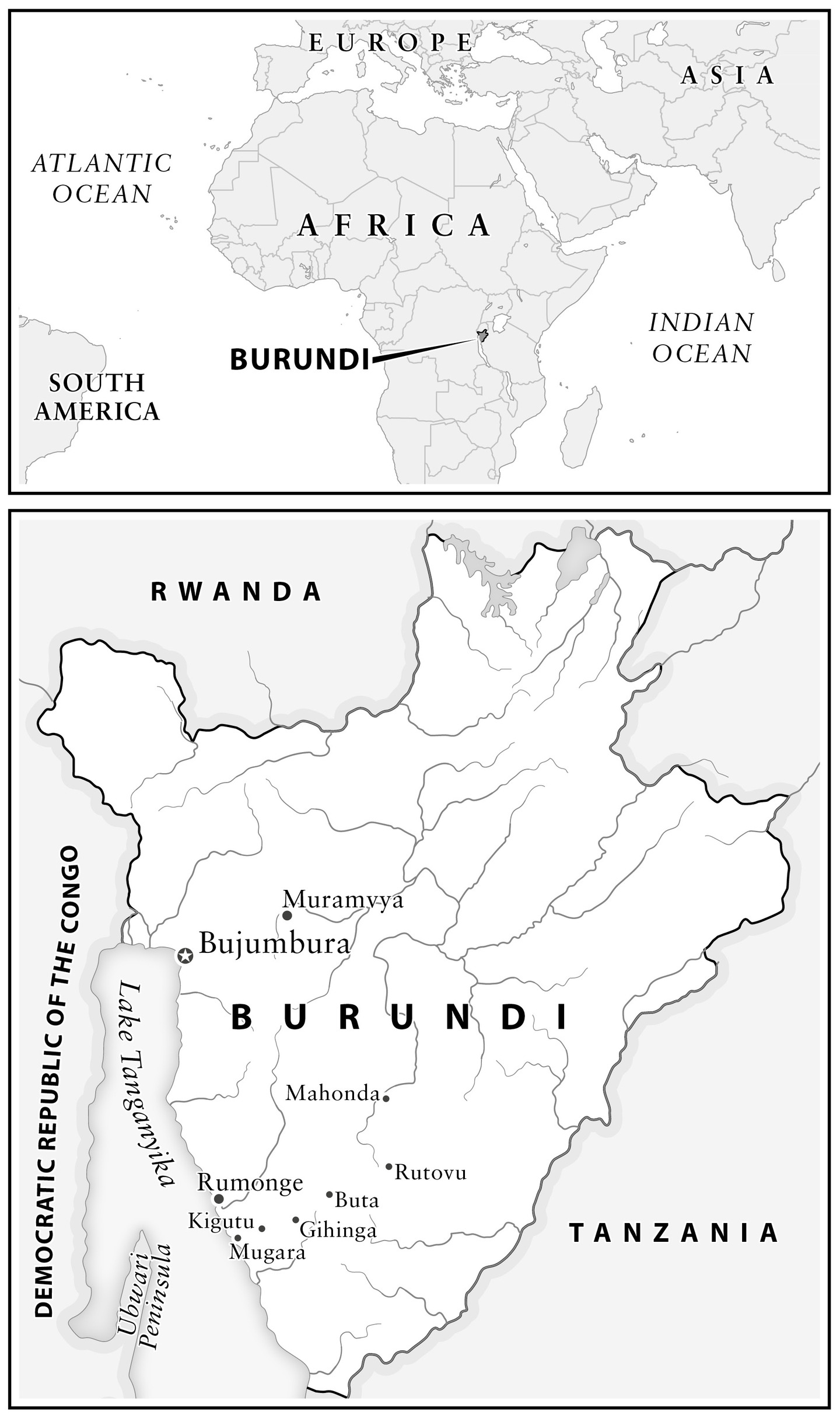

Maps copyright 2022 by David Lindroth Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Irankunda, Pacifique, author.

Title: The tears of a man flow inward: growing up in the civil war in Burundi / Pacifique Irankunda.

Description: First edition. | New York: Random House, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021011222 (print) | LCCN 2021011223 (ebook) | ISBN 9780812997644 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780812997651 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Irankunda, PacifiqueChildhood and youth. | BurundiHistoryCivil War, 1993-2005Personal narratives.

Classification: LCC DT450.863.I73 A3 2022 (print) | LCC DT450.863.I73 (ebook) | DDC 967.572042092dc23

When I took my grandpas cows to pasture, in the land of sorghum to which we had fled, I often found myself singing a sad and soothing song. When I felt tears streaming down, I wiped my eyes and repeated to myself what I had heard the adults say: that the tears of a man flow inward.

I find it hard to look back to Burundi, because I have always tried to look ahead. Always. Even as I think these words, looking out my window in Brooklyn, I realize I am nevertheless looking back.

I live in a spacious apartment, with six windows facing the water of New York Harbor. It is on the top floor of an apartment building so large it occupies the entire block between Shore Road and Narrows Avenue, next to the Verrazano Bridge. Below Shore Road lies the Belt Parkway. And below the Belt lies the Shore Promenade, and then the harbor, and across the harbor, Staten Island. I like to sit by my living room window, six feet wide, and gaze at the view. I gaze at it every day of the year, and not once have I tired of it.

When I lower my eyes, I look at a rose garden and water fountains and trees, and when I lift my eyes, I watch cruise and cargo ships pass by. These ships are enormous, and they come from all over the worldfrom Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Caribbeanbringing people and merchandise to New York. Local ferries and small boats and yachts go by faster than the great ships, which move slowly toward the harbor and slowly seaward toward the Narrows. Every cruise ship that passes grabs my attention. When there are no boats or ships out there, I find myself gazing long and longingly at a distant view. Instead of New York Harbor I see a view from the hilltop in Kigutu, my native village in Burundi.

I look out over Lake Tanganyikathe worlds longest lake and second deepesttoward the peninsula of Ubwari, in the dark mountains of eastern Congo. I stare at the distant view and begin to journey back in thought. Then a cruise ship passes in front of me, grabs my attention, brings me back to Brooklyn, and makes me realize, as if awakened from a dream, that I was looking back. And I hear a voice stored somewhere in my mind, telling me not to look back.

It is the voice of my brother Honor, telling me, as if Id never heard it before, the story of Lots wife, who looked back and turned into a pillar of salt. Hearing Honors voice in my mind takes me right back to Burundi, when I returned there during my winter break from Williams College. I still see the image of Honor, standing in the yellow savanna grass dotted with small eucalyptus. He is telling me not to look back.

Years before, our mother, Maman Clmence, had given me the same advice more gently, saying to always look ahead. However, my older brother drilled dont look back into my psyche, so much so that it has disturbed me, causing a mixed effect: neither steadily looking ahead nor daring to fully look back, as if I have become a pillar of salt. Vladimir Nabokov wrote in Speak, Memory that time is a prison, and I sometimes feel as if I am one of its inmates.

I find it hard to look back because most of what I see when I look back is painful. One doctrine of Western psychology has long held that the cure for the pain of memory is a return to the past itself. Burundian culture holds an opposite view. I now realize that each approach has its own wisdom. But for me the past is inescapable.

In the late afternoon, the view from my window in Brooklyn brings me a feeling of peace, which reminds me of looking after cows. I liked to sit at the hilltop and watch the view of Lake Tanganyika while watching my family cows. I would gaze at the water in the lake and then gaze at the cows grazing.

I didnt know then that the cows of Burundi were unusual, because I didnt know that there were other kinds of cows. Ours were tall and long-legged and had enormous horns that could reach a span of ten feet from tip to tip, rising like cathedral arches above their peaceful-looking faces. They were called inyambo, and they were the most ancient of domesticated cattle, descendants of the biblical ox. Historians claim that these cows were present in the Nile Valley some four thousand years before historic times. Drawings of them were found on cave walls and ancient Egyptian monuments. Inyambo were known as the Cattle of Kings, although ordinary people owned them. One of my siblings had named himself Beninka, which means, literally, To Whom the Cows Belong; and my father was named Buhembe, the name of their long horns. Out of those long horns people made trumpets called inzamba. When I am asleep in Brooklyn, I sometimes hear a foghorn from departing cruise ships in New York Harbor; it makes a beautiful sound in the night, sad and distant, and it always makes me think of trumpets, of war, and of ancient times.

Like a person, my country had a name and a surname. If in bureaucratic American English I am Irankunda, Pacifique, then my country is Burundi, Milk and Honey. In the past, there had always been plenty of milk and excellent honey there. Beekeeping and the uses of honey had a place of importance in my countrys traditions, and so did cows and their milk. As a child, I assumed this was my countrys real name. Had I been asked, at that time, where I came from, I would have innocently said, Milk and Honey.

That country no longer exists. It was the old Burundi, a country of storytellers, of people who invented myths and systems of justice and a set of traditions that had become folklore. Cows were a living relic of this old time, and in my family they were still treated and loved the way they had always been in the time of kings. Imana, God, was often referred to as the creator of cows and childrenthe two most adorable, precious gifts from Imana. When expressing shock or an exciting surprise, some Burundians invoked Imana, saying