Contents

Guide

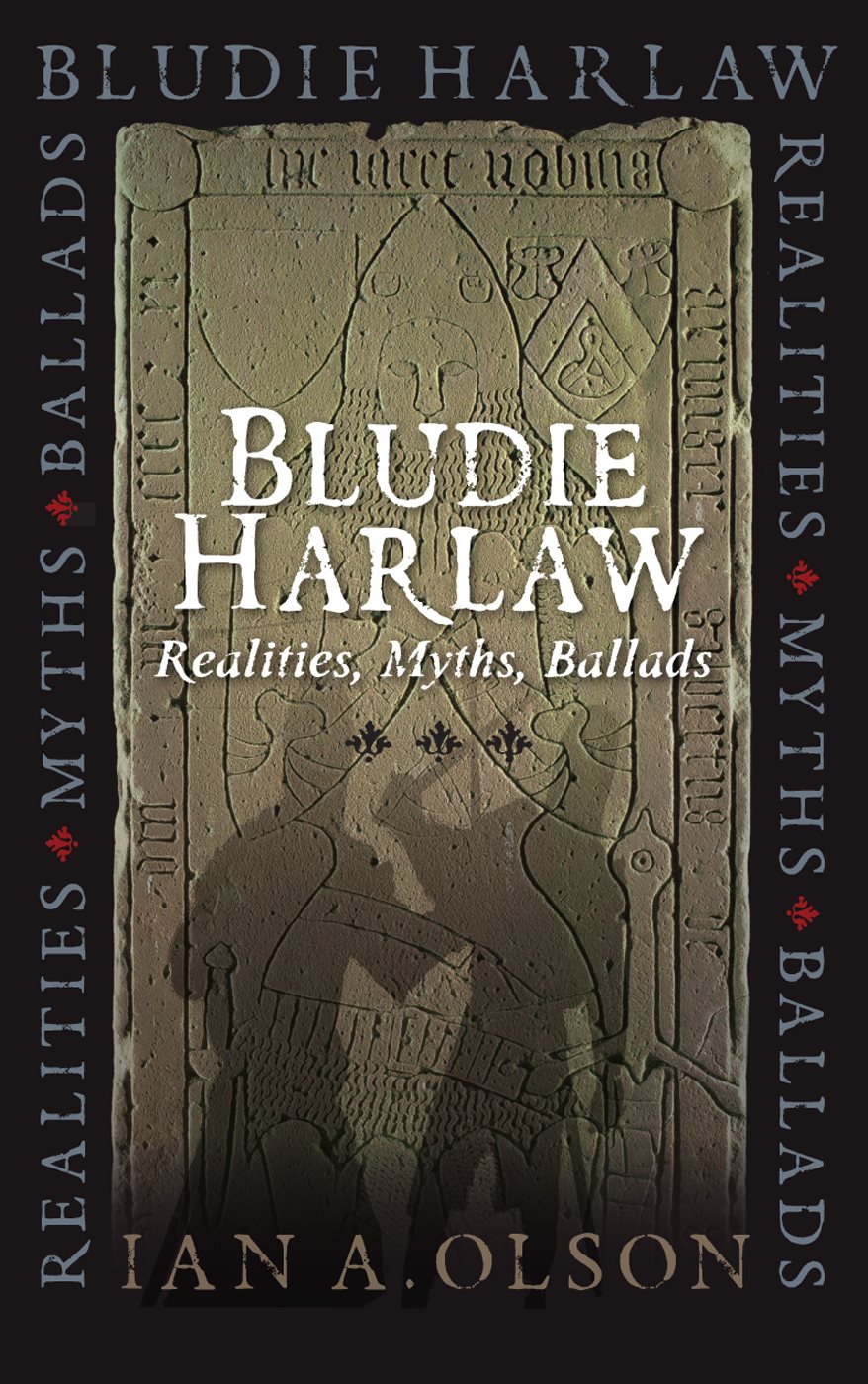

Bludie Harlaw

Bludie Harlaw

Realities, Myths, Ballads

Ian A. Olson

Heir the bludie battel of the Harlaw was fochtine; gret slachter on baith handis, mony alsweil knychtes as utheris nobles war na mair sein.

Father James Dalrymple (1596)

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

This paperback edition first published 2021

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 788855 40 2

Copyright Ian A. Olson 2014

The right of Ian A. Olson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset in Warnock by Koinonia, Manchester

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf, S.p.A.

For Elizabeth

Trustworthy accounts of this famous fight there are none. Lowland historian and ballad composer, as well as Highland seanachie, described what they believed must and should have happened.

Clan Donald historians (1896)

Much has been written about that battle, and some of it is pure fiction.

Irvine of Drum historian (1998)

Contents

List of Illustrations

Plates

Map

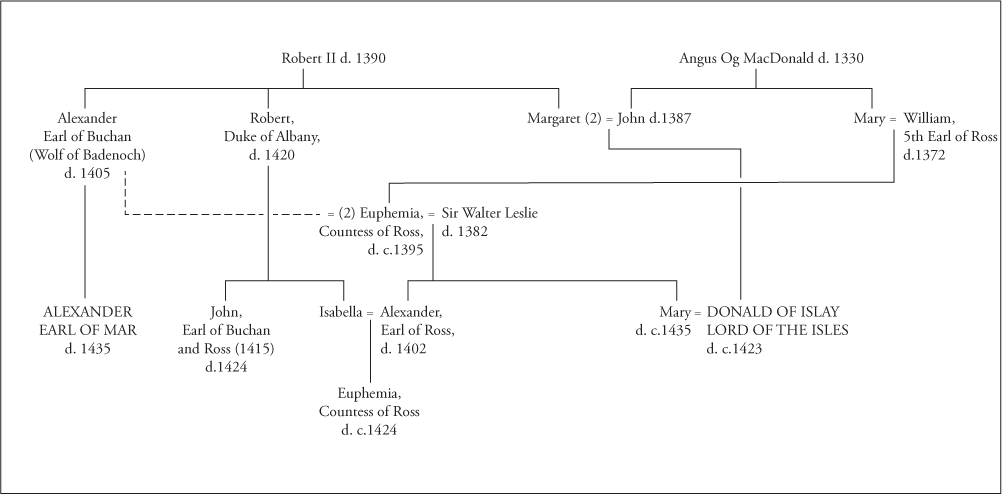

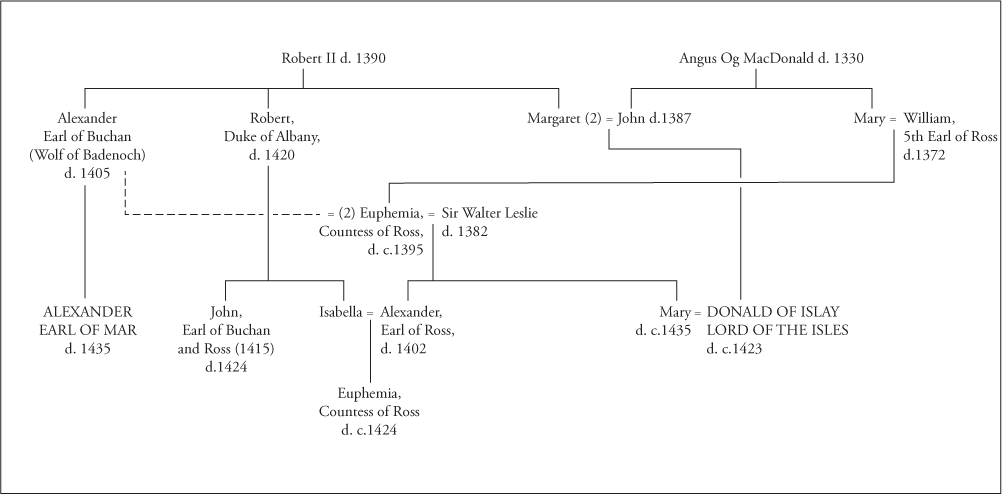

Genealogical Table

Figure

The Geography of the Battle

Claims to the Earldom of Ross

1

Introduction

I n the summer of 1411, Donald of Islay, Lord of the Isles, invaded mainland Scotland with a huge, battle-hardened army, only to be fought to a bloody standstill on the plateau of Harlaw, fourteen miles from Aberdeen, a town he had threatened to sack. The ferocious battle was described by even hardened mediaeval chroniclers as atrocious, with some three thousand dead, dying and wounded on the field.

It should stand as one of the greatest battles ever fought in Scotland, ranking easily alongside Bannockburn or Flodden in size and significance, but it has largely faded now in memory, other than that of Aberdeen, where its deliverance is still celebrated (on the wrong day, because of old and new calendar confusion) at a stark monument commemorating those who fought at Red/Reid Harlaw, high on the hill.

Walter Scott dismissed it as having settled for once and for all whether or not Celt or Saxon should rule Scotland, a political comfort perhaps for a Britain still shaken by the memory of the Jacobite Risings of wild Scots from the West.

Written records of Donalds invasion exist in Latin, Scots, Gaelic (only one, alas) and English. Lowland versions tend to dominate, mainly because there had been serious destruction of Highland accounts, especially of the records of the Lords of the Isles themselves. Records also fall into two main groups a first set written at or around the time, and a second set composed some 300 years later. These later histories tend to be both romantic and highly imaginative, creating noble order where chaos existed before and form the basis of most popular descriptions of the battle.

There is an unfortunate tendency to view Scottish history as a series of clan battles Harlaw, especially, being seen as Macdonalds versus Stewarts which were terminated in the aftermath of the Jacobite It is during this post-Risings period that the second set of Harlaw histories, many with strong racial connotations, begin to appear.

For over a hundred years serious historians have studied the Lordship of the Isles, the earldoms involved in the battle Ross, Mar and Buchan the great families and the Stewart kings of those times, weaving a rich tapestry from the period, a tapestry, like the Bayeux, which evolves over time, reflecting constantly changing allegiances and alliances made and broken as circumstances permitted or encouraged. Geographically it extends from Norway across to the Isles and over to Ireland, from mainland Scotland to England, and even to France, for it is a mistake is to view Donalds invasion, as some do, as a relatively local matter, affecting principally the North-East of Scotland.

From this gratefully acknowledged tapestry I have attempted to draw out the threads of why the greatest magnate in Scotland should have taken an excessive gamble by invading, antagonising and horrifying the mainland Scots, all for apparently to make a claim for the Earldom of Ross. The threads are the written records which are presented here both in original form, and with transcriptions and translations.

Two major ballads are included, one probably written around the time and perhaps shedding some light on the conflict, and one fabricated over 350 years later; despite being sung to this day, this latter is of almost no historical value at all. The Complaynt of Scotland, published around 1550, depicts a group of shepherds and their wives amusing themselves by singing sueit melodious sangis of natural music of the antiquite, one of which was entitled the battel of the hayrlau, but the title alone was given. As they may well be of much later composition, commemorating a great past tragedy, as the Scots do so well, I have not included them.

Over the centuries, Highland poets and bards have alluded to the battle, and praised patrons by referring to their ancestors involvement I have thus confined myself to descriptions and arguments given in prose accounts from either side of that conflict.

The early descriptions of the battle were superceded by very much later stories. These accounts, especially the most influential such as Tytlers, have drawn on few, if any, fresh sources, yet they form the firm and confident basis both of folk memory and modern accounts of the conflict, demonstrating the remarkable power of such transformative stories. This has necessitated my recounting the battle and its aftermath several times, in English, Scots and Gaelic, in order to show the differences between the early histories and later accounts as well as those between Highland and Lowland versions. The Latin originals are provided in .

It is twenty-five years since I first asked the late David Buchan about his initial research on the Harlaw ballads. I was then beginning to explore the ragged and apparently unreliable interface between such balladry and Scottish history. This was an interest in Scottish history that had been aroused by the then Albany Herald, Sir Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk, first when a patient of mine, and thereafter as a good friend and guide, a man who combined a remarkable attention to detail with a delight in his subject.

One of the great pleasures in studying Scottish history is the fact that descendants of those who played a part in events such as the Battle of Harlaw are not only still with us, but are more than helpful in the untangling and understanding of the past. Consider, for example, Robert Maitland of Balhalgardys family they have farmed the site of Harlaw for over six hundred years; his ancestor left the plough to join the battle.