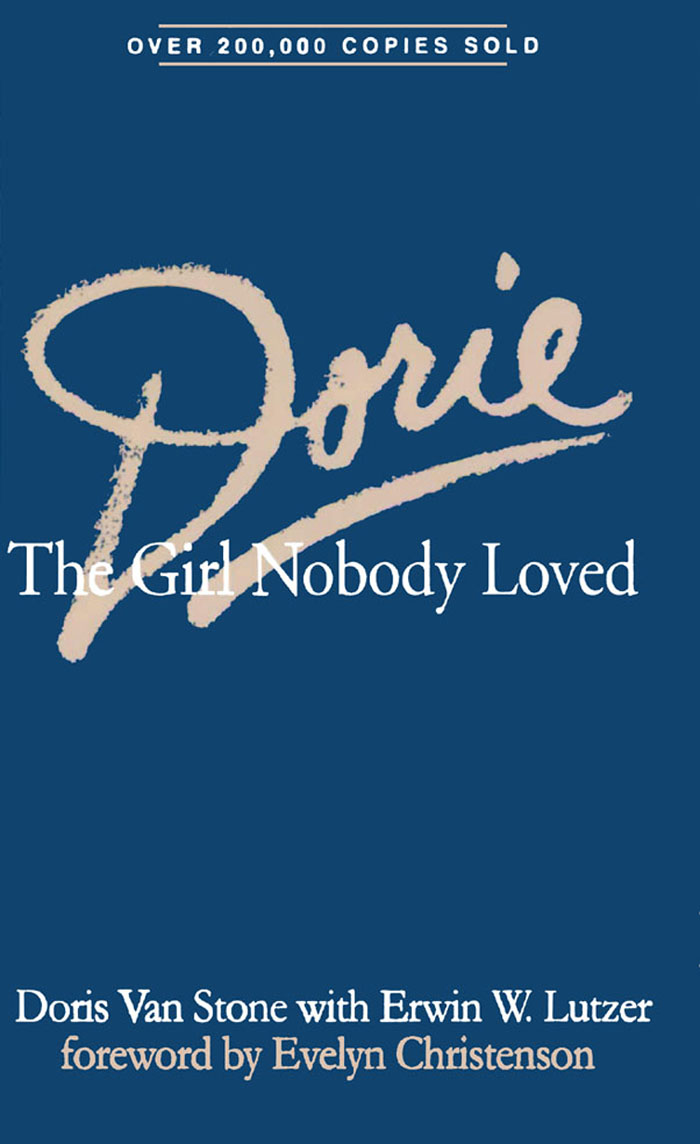

Doris:

THE GIRL NOBODY

LOVED

DORIS:

THE GIRL NOBODY

LOVED

DORIS VAN STONE

with

ERWIN LUTZER

MOODY PUBLISHER

CHICAGO

1979 by

The Moody Bible Institute

of Chicago

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Van Stone, Doris.

Dorie, the girl nobody loved.

1. Van Stone, Doris. 2. MissionariesNew GuineaBiography.

3. MissionaryUnited StatesBiography. I. Lutzer, Erwin, joint author. II. Title.

BV3680.N52V358 266.0230924 [B] 78-17935

ISBN 10: 0-8024-2275-6

ISBN 13: 978-0-8024-2275-0

Moody Paperback Edition, 1981

We hope you enjoy this book from Moody Publishers. Our goal is to providehigh-quality, thought-provoking books and products that connect truth toyour real needs and challenges. For more information on other books andproducts written and produced from a biblical perspective, go towww.moodypublishers.com or write to:

Moody Publishers

820 N. LaSalle Boulevard

Chicago, IL 60610

33 35 37 29 40 38 36 34

Printed in the United States of America

To

Burney and Darlene

who gave me

the privilege of being called

Mother

Contents

I read with tears in my eyes this powerful story of the little girl nobody loved turning into the woman God chose and used. Humanly speaking, Dories childhood of unbelievably cruel treatment and total rejection should have produced an emotionally unstable, bitter adult. But instead, Christ, as her newfound Savior, rescued her and, little by little, transformed her into a well-adjusted adult.

I was moved by the way Dorie was miraculously sustained by her only material possession, a little New Testament, during her time of terrible aloneness in the world. She underlined, memorized, and clung to its promises. It was her only friend. But it proved to be sufficient.

This story shows beautifully how one can crawl out from under a self-image of complete ugliness not only into Gods acceptance and love but also into a successful ministry for Him. It is a fantastic picture of Christ understanding and caring for and lifting up an unloved, beaten, and neglected child, and then healing her and miraculously preventing a permanent emotional scar.

But to me the most beautiful part of Dories life is that she is now using her childhood experiences to help other battered children work through their hurts, bringing them the same hope she foundJesus.

EVELYN CHRISTENSON

I walked quietly to the window and stared into the darkness. My eyes followed the headlights of each passing car. I sat on my brown wooden stool, my hands tucked under my legs, trying desperately to keep warm.

Hours passed. Finally I saw the shadowy form of my mother turn the corner and come up the walk. By the time she reached our second-floor apartment, I had groped through the dark room to meet her.

I hope shell be glad to see me. But as usual she brushed past me and gathered my sister Marie into a hug. Honey, how are you? she cooed. I stood, my hands stuffed in the pockets of my faded coveralls, waiting for her to love me. But she pushed me away. What do you want? she barked.

Would you hug me? I asked timidly.

You get out of here! she barked back.

I was only six. But scenes from that apartment are etched indelibly on my mind. I remember nothing bright. Dark woodwork trimmed the drab walls. A brown overstuffed chair, a bench, and a small rug furnished the front room. The next room was bare except for a bed, shared by Marie and me, that pulled down from the closet.

Each morning my mother left early and was gone until late at night. I can still see herjet black hair framing her perfectly oval face. Her brown eyes turned stony as she shouted, Doris, take good care of your sister. And remember, dont turn on the lights!

Marie was a year younger than I, and my mother was anxious for me to understand one thing clearly: if anything happened to Marie, I would be blamed. The responsibility rested with me.

Marie and I spent our days in the apartment alone. We looked forward to the weekends when Mother would fix us something to eat. On those mornings she slept late, and then the three of us ate together in silence. But most of the time our menu consisted of the only food a six-year-old can fix: peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. I could reach the jar in the pantry. Holding the jar between my knees, I twisted and scraped with a knife to mix the oil and peanut butter. Dont spill the oil, Mother had warned. If I did, I quickly mopped it up with toilet paper. I spread the peanut butter, gouging holes in the bread. If we had no jelly, we gulped it down as best we could.

Occasionally we had milk, but usually we drank water. We had no tin tumblers, only jelly-jar glasses. Having been whipped for breaking one of them, I learned caution. I pulled a chair up to the porcelain sink set the glass under the spout, then turned on the water. With both hands, I passed the glass to Marie, then climbed down.

Our stomachs often growled with hunger. Once I bravely walked to the store, hoping the grocer would give me some food. When he said no, I promised that my mother would pay the next day. I learned that only people with money could have food. Reluctantly, I walked home to the apartment empty-handedand hungry.

Each evening waiting for my mother, I felt alone, responsible. I was terrified that something awful would happen to me or my sister. The darkness of our dingy apartment fed my childish imagination. What if Mother doesnt come home?

One evening we heard the door open on the first floor of the apartment building. I grabbed a butcher knife from the kitchen, opened the door of our apartment, and saw two drunks standing at the bottom of the stairway. Clutching the knife till my knuckles turned white, I yelled, Get out! Ive got a knife! with all the fierceness I could muster. Marie hid behind me. They laughed, then left a few moments later.

When I reported the terror to Mother, she shrugged. So? They didnt come in, did they? Then she asked the only question that mattered. Did you have the lights on?

Thats why I put my chair next to the window. The car lights moving along 34th Street in Oakland, California, were more friendly than the haunting darkness of the cold apartment. I was afraid to fall asleep without Mother there. Sometimes Marie would cry out, terrified by strange noises. I would calmly put my arm around her shoulders, telling her not to worry. Inside I was terrified. Night after night I sat in the dark and worried about what Mother would do to me if Marie became sick or was hurt.

When Mother did arrive late in the evening she didnt speak to me but always quickly went to find Marie, who usually had fallen asleep on the couch. Marie is a pretty girlshes not like you, my mother would often say. She tucked Marie into bed and kissed her good night. I was on my own.

Without changing my clothesI had no pajamasI crawled under the covers next to my sister. Not once did my mother hug me or let me sit on her lap.

Occasionally, my mother would bring a gift for Marie, but never for me. Our clothes were given to us by our friends next door. Our dresses always seemed to be either too small or too big; our trousers were worn bare at the knee, and our shoes pinched our toes. Anything new was given to Marie.