CONTENTS

8 (StJean/Kitchener Wood)

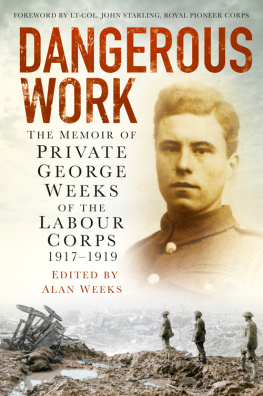

This is my fathers account of his war experiences on the Western Front between 1917 and 1919, edited by me. This was handwritten after the war on seventy-eight sheets of cut-up wallpaper. They were in a box file left to me by my father. Notes and comments are included in the main text but are shown in a different font this is to assist in the reading of the document, otherwise the reader would be continually looking up references elsewhere. I have added two simple maps so that the reader may follow Georges movements in northern France and Flanders.

Alan Weeks

In fifteen years of research into the role and activities of the Labour Corps this is the only soldiers diary I have ever seen. What makes it even more remarkable is the fact that for a corps that was to involve over 500,000 British officers and men there are only three known records and these were all by officers and written after the event when events could be judged in retrospect.

The diary makes interesting reading. It is the thoughts of a private soldier that have not been rewritten after the war. It does not involve great military actions but day-to-day survival in terrible conditions. It is quite obvious that world or national events have little or no concern to Private Weeks and his comrades who are involved in the daily grind of maintaining roads and railways.

The Labour Corps was one of a number of units that was formed during the war and disappeared soon after the war finished. Their activities are generally unsung and there were few formal records of their achievements; the units did not maintain war diaries. When Britain entered the European war in August 1914 all planning was based on a short war fought where local labour was easily available and tonnages of equipment were limited (siege warfare was not envisaged). France was different: most of the available manpower in France was conscripted to serve in the French Army and so the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had to maintain its own supply lines.

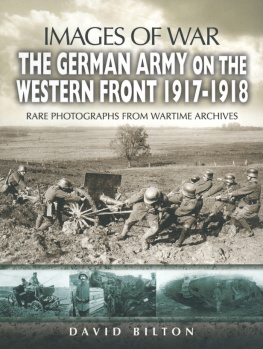

When the BEF deployed it was mainly an infantry-heavy force with limited artillery and was not equipped for the drawn-out siege warfare experienced from November 1914 onwards. In 1914 the army was using about 10,000 tons of ammunition a month but by June 1917 this had risen to 230,000 tons a month. Add to this food, fuel (including fodder), trench stores (sandbags, props, pickets etc.), medical supplies and all the other equipment, and you can see what a massive effort was required to unload from ships in France, load trains, transfer to light railways and roads, and finally move stores to the front on mules and by men. It should be remembered these were the days before material-handling equipment and all stores were moved by hand. At the same time railways and roads were laid, upgraded and maintained by a significant uniformed workforce.

The first labour units were deployed to France in early 1915 to work in the docks and maintain the railways. As the army grew, so did the demand for labour. In 1916, with the introduction of conscription, more men were being enlisted of lower medical category and over the accepted age limit of 35 for the infantry. These men, many suffering minor physical ailments like short-sightedness and from poor nutrition, were placed into infantry labour units and moved to France.

In April 1917 all the various forms of labour infantry, Army Service Corps, Royal Engineers, prisoners of war etc. were placed under a single command and the Labour Corps was formed. Many units did not take to being referred to as Labour Corps and you will note that George continually refers to the Queens Regiment because his company, 132 Company Labour Corps, was previously 24 (Infantry) Labour Company the Queens Regiment. Being a labourer and not a soldier had a certain stigma and as a result even the army ensured that medals and any graves were marked with the servicemans original regiment (if he had one).

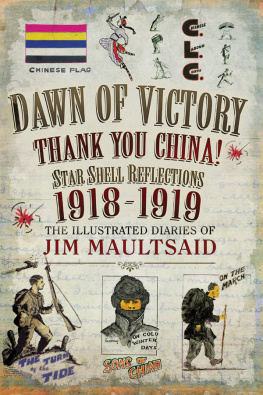

With the massive increase in labour units due to conscription there were still shortages. By November 1918 there were over 395,000 members of the Labour Corps. Eventually the British looked to their empire for support and Indians, Africans and West Indians came to France. By the end of the war there were 98,000 Chinese employed by the Labour Corps.

Following the war, the Corps was involved in battlefield salvage, which was to recover valuable material from the battlefield. It was not the British Armys problem to return the battlefield to farmland. Whilst carrying out this work the Corps also underook the task of concentrating the various battlefield graves into what are now the Commonwealth War Grave Commission cemeteries in France. This task proved so demanding that men who had left the service were asked to re-enlist to undertake burial duties.

Georges diary makes interesting reading. He was a volunteer from a reserved occupation and being medically downgraded to C2 meant he did not have to join. His experiences reflect those of the many thousands of men who were in the Labour Corps; he has little knowledge of events outside his own section of twenty-eight men, and interestingly, even though he knows he joined 24 (Labour) Company, Queens Regiment, when that forms into the Labour Corps he seems unsure of the company number. He reflects the attitude of many of the men transferred to the Labour Corps in that he continually refers to his old regiment and cap-badge rather than the new organisation.

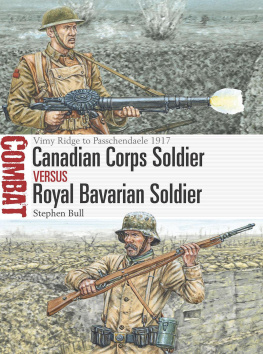

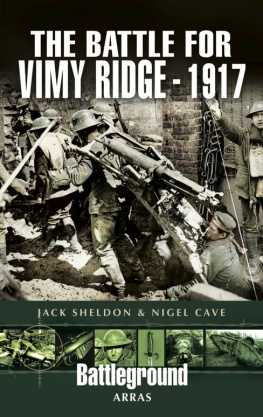

Throughout his service he visits all the main combat areas, starting with clearing up the old Somme battlefield, moving to Ypres to maintain roads during the battle of Passchendaele and, although not in the line during the March offensives, being actively employed in producing the GHQ Reserve Line. After the allied advance in August 1918 he followed the advancing army into German-occupied Belgium and finally into the occupied zone of Cologne.

His experiences show that although the Corps was not in the front line its members spent many long periods within the range of enemy artillery without relief. The front-line infantry tended to rotate between front line, support and reserve/rest/training (outside of enemy artillery range). George himself spends a long period at Kitchener Wood, Ypres, building an artillery-locating facility which is abandoned. Other records I have seen show men maintaining light railways, within the range of enemy guns for up to six months without a break. It must be remembered that all these men were of low medical category.

Although initially unarmed, the Labour Corps was not non-combatant. The non-combatant corps consisted of conscientious objectors, whereas the Labour Corps tended to be personnel who had been medically downgraded due to wounds or age. Had the original companies been armed, a lot of work would have been lost as the men undertook weapons training etc. Following the March 1918 offensive, a decision was made to arm the whole Labour Corps, to enable its men to defend themselves and certain areas of the line, but this took time.

Georges Unit, 132 Company, although a labour company of five officers and 425 men, does not fully reflect all 300 British labour companies at the front. Since it was employed in relatively quiet zones it suffered remarkably few casualties, and there are only two recorded Meritorious Service Medals and no gallantry awards. Some units were unlucky and ended up bearing the brunt of the German advances in 1918.

I wish that this script had been available when I was researching the work of the Labour Corps as it fully represents the role played by many thousands of men, both British and foreign (Indians, Africans, Chinese etc.), within the corps in France.

Next page