Though this be madness, yet there is method int.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet , Act II

I am indebted to the staff of the superb Highland Archive Centre in Inverness, in particular Colin Waller, for their help and their courtesy in allowing me access to records of Craig Dunain Hospital.

The British Journal of Psychiatry kindly granted me permission to use material from A Fifteen-Year Review of Female Admissions to Carstairs State Hospital by Patrick W. Brooks and Geoffrey Mitchell, which appeared on pages 4457 in the issue of November 1975 (No. 127).

My sincere thanks go to those former patients of the State Hospital who kindly told me of their experiences at and memories of Carstairs, while requesting anonymity and in one case overcoming great distress at certain recollections.

I am grateful also to Robert Mone, still in the custody of the Scottish Prison Service, for providing a series of statements relating to the incident in 1968 that resulted in his becoming a Carstairs patient, his knowledge of Thomas McCulloch and the events surrounding their escape in 1976. This is the first time that either man has voluntarily made public a precise account of the escape.

CONTENTS

1800 | Criminal Lunatics Act gives the sovereign power to order the safe custody of criminal lunatics but makes no provision for the cost of their upkeep. |

1855 | Doctor David Skae, physician at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, calls for a single institution to detain criminal lunatics. |

1865 | Scotlands first criminal lunatic department opens at Perth prison. |

1877 | A prison service report complains of a lack of accommodation in the lunatic department at Perth. |

1933 | The first escape from the Perth criminal lunatic department by a female. |

1935 | The government admits Perth is unsatisfactory and says the question of building a new place to hold criminal lunatics is getting active consideration. |

1935 | Details are revealed of a Bill authorising the building of the new proposed lunatic asylum at Carstairs. |

1937 | The government decides it needs Carstairs accommodation for military use, and the facility is used as an army hospital throughout the Second World War. |

1941 | Seven men escape from Perth criminal lunatic department. |

1948 | The army no longer require the facility at Carstairs, and it finally opens as the State Institution for Mental Defectives. |

1950 | Thomas Howie drowns in the River Tay after escaping from Perth criminal lunatic unit. |

1957 | Ninety criminally insane prisoners are transferred from Perth prison to Carstairs. This combined unit becomes the State Mental Hospital. In the same year, John McGhee and John McDade escape from the facility. |

1959 | The first female patients are transferred to Carstairs. |

1962 | Iain Simpson is sent to Carstairs for murdering two hitchhikers. |

1963 | The government announces plans for enlarging Carstairs. |

1967 | Robert Mone shoots dead schoolteacher Nanette Hanson at Dundee and is sent to Carstairs. |

1968 | Carstairs nurses giving evidence to an inquiry into bullying and staff safety tell of being subjected to Belsen and Gestapo taunts. |

1970 | Thomas McCulloch is sent to Carstairs after a shooting incident at the Clydebank Hotel. |

1972 | The escape from Carstairs of Alexander Reid and Malcolm McDougall sparks fury. Three nurses are suspended. |

1973 | Robert Mone and Thomas McCulloch begin a relationship at Carstairs. |

1973 | A sheriff rules that natural justice rules dont apply in mental cases. |

1976 | Mone and McCulloch escape, murdering three men, patient Iain Simpson, nurse Neil McLellan and policeman George Taylor. |

1977 | Carstairs management is severely criticised in an official report on the formal inquiry into the escape of Mone and McCulloch. |

1978 | Former Carstairs patient Robert Gemmill gets life imprisonment for murdering a teenage schoolgirl. |

1994 | Patient Noel Ruddle is disciplined after a Christmas party at Carstairs leads to the discovery of drugs and drink. |

1998 | Patients make legal moves to be released from Carstairs, arguing they are sufficiently cured to be transferred to prison. |

2012 | The major rebuilding of Carstairs is completed at cost of almost 90 million. |

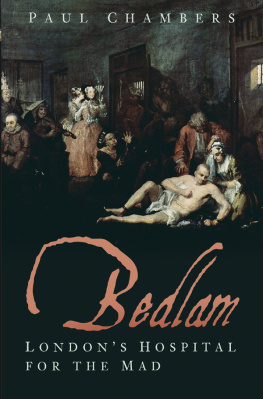

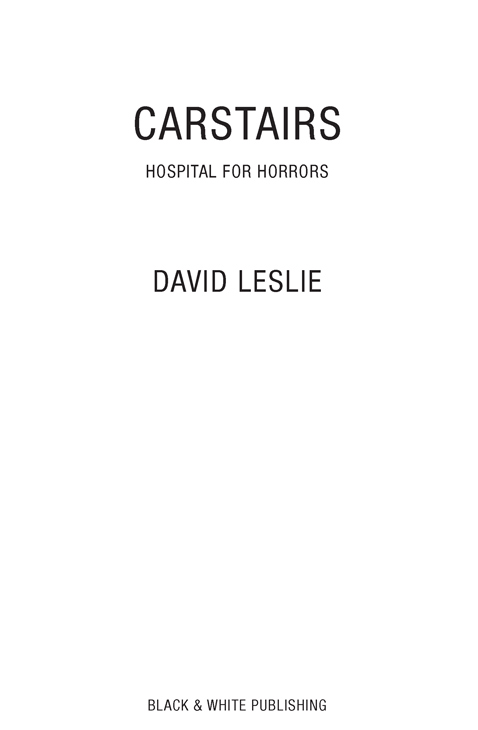

It is officially termed the State Hospital but to most it is simply Carstairs. That word alone is sufficient to send a shiver down the spine, because Carstairs is no ordinary hospital. It is effectively a prison holding the most seriously demented and dangerous men in our society, among them the perpetrators of hideous crimes. Some have psychiatric illnesses so deep-rooted that they are untreatable. All are there to protect them from us; and we from them. In short, it is a hospital for horrors.

The common image of Carstairs as a terrifying pit of evil where patients are subjected to torture and humiliation is one largely resulting from the refusal of successive managements to illustrate to the public who fund it precisely what goes on behind its barbed wire and bars. Secrecy is paramount. Officially, staff must never discuss their work. Some former patients believed that should it become known they had discussed their experiences, they would be hauled back inside, never to re-emerge. In compiling this story of Carstairs and the how and why it came into being, the State Hospital was invited to become the major contributor. It refused. Carstairs is akin to the very thing that it seeks to treat: the human brain an organ locked within a fortress refusing to give up the secrets of its working.

Carstairs: Hospital for Horrors tells the story of Scotlands State Hospital through the stories of the people that have been incarcerated there over the years. This book concentrates on the crimes which led to them being committed there, the challenges they pose for the State Hospital, the problems with security and the (often misguided) decisions to release them from the facility. The lack of cooperation from Carstairs in writing this book has meant that it is not possible to explore the treatments that are used at the facility or the security measures in as much detail as necessary. This secretive approach from Carstairs administrators discourages sympathy for its patients. And yet, tragically, sympathy and understanding are what patients need and deserve. For centuries, madness has been a condition largely regarded with sympathy even though the care of sufferers has lacked support. There was little or no discrimination between the varying degrees of severity of psychiatric illness, often simply the product of poverty, with the result that the afflicted were frequently simply left to mingle with the sane, void of treatment or help. Records held at the Highland Archive Centre in Inverness show how often seriously disturbed men and women were thrown together to sink in their despair or swim back to sanity.

Next page