IMAGES

of Modern America

THE 1910

WELLINGTON

DISASTER

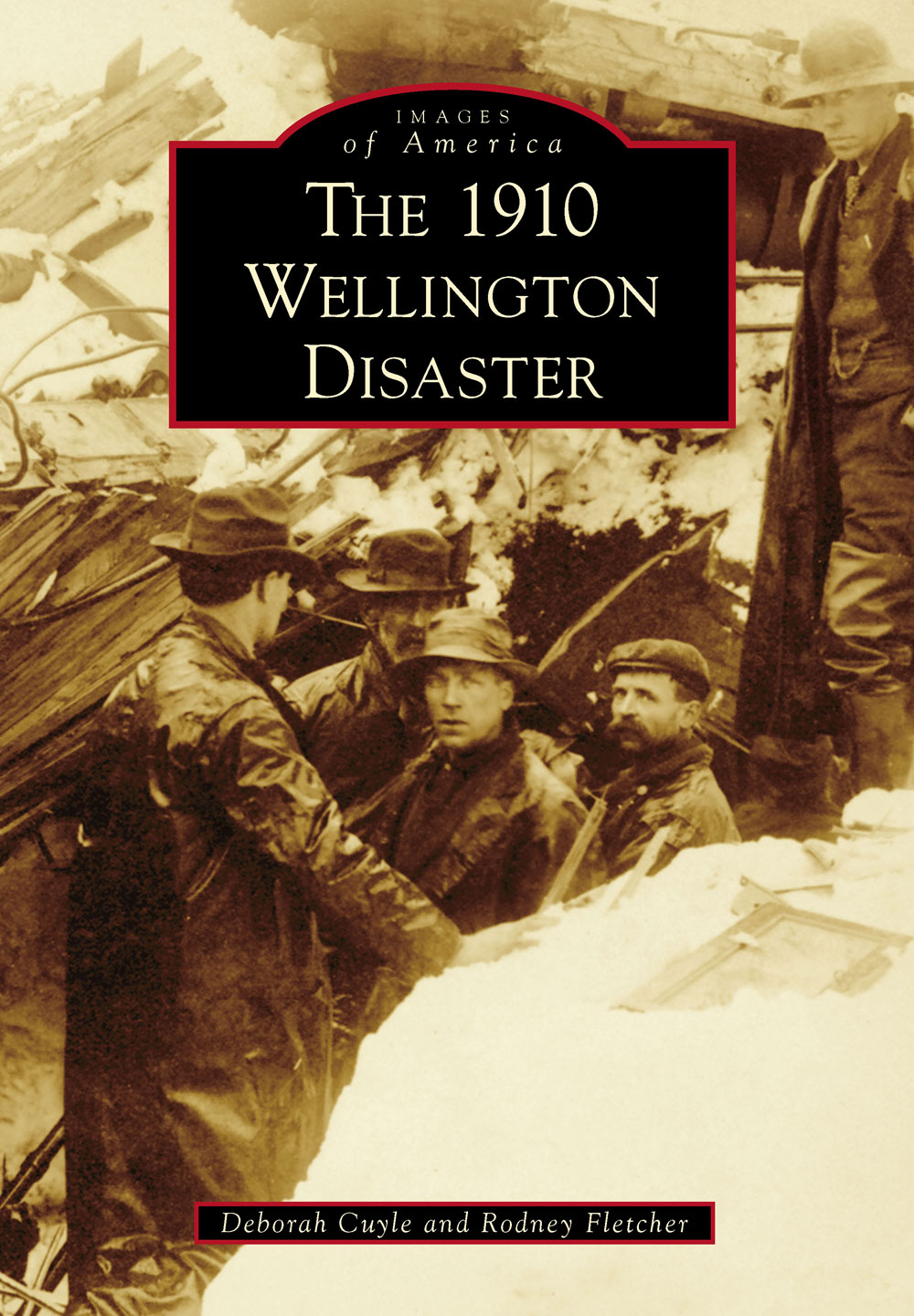

ON THE COVER: Supt. James ONeill (center) and unidentified men sift through the debris searching for victims and hopefully more survivors. The wreckage was buried beneath approximately 40 feet of snow. (Courtesy of John A. Juleen Collection, Everett Public Library.)

IMAGES

of America

THE 1910

WELLINGTON

DISASTER

Deborah Cuyle and Rodney Fletcher

Copyright 2019 by Deborah Cuyle and Rodney Fletcher

ISBN 978-1-4671-0273-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439666159

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955296

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

We write this dedication on the evening of the 108th

anniversary of the Wellington disaster. God rest your

souls in Heaven, each and every one of you.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge all history lovers, as they work hard to do all they can to preserve and protect our past for future generations to enjoy. Bob Kelly with the Skykomish Historical Society is foremost; without his vast knowledge of and interest in Wellington, this book would not be possible. The Wenatchee Valley Museum was wonderful and supportive of the project; they have an amazing collection. The Northwest Railway Museum was also a great help and has wonderful Wellington links on their website.

Dozens of other individuals went out of their way to help scan photographs and dig up materials, and we are grateful for their valuable time and energy. There are too many of you to list here, but rest assured we appreciate you.

We also acknowledge all of those from 1910 who were involved in fighting the horrific storm and fatal avalanche that night. They put up a good fight, even if they did not win.

And as always, thanks to the friendly and supportive team at Arcadia Publishing, for all they do to preserve and promote local history. Their dedication is infectious, and their endeavor vastly important.

Images appear courtesy of Bob Kelly and the Skykomish Historical Society (SHS), the Library of Congress (LOC), Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center/Oliver Loch Chapple Collection (WVM), and the John A. Juleen Collection, Everett Public Library (EPL).

All witness statements were taken from the transcript of testimony at the coroners inquest after the disaster, courtesy of the Washington State Archives.

It is a federal offense to remove any artifacts from the Wellington site. Please respect this law, as leaving artifacts allows others to experience Wellington. We ask that the site remain untouched by trash and graffiti. Thank you.

INTRODUCTION

During one of the worst storms in the history of the Cascades, unsuspecting passengers on two Great Northern (GN) trains became trapped in the remote mountain wilderness for almost a week surrounded only by strangers, with the trains perched precariously on the side of a mountain and thousands of tons of snow looming overhead. At night, they tried to sleep, even with the eerie sounds of a nearby avalanche rumbling down the slopes taking everything in its path. Passengers on the Seattle Express No. 25 and the crew of fast mail No. 27 were definitely stuck, with their trains slowly being buried. Each restless day and every long, dreadful night, they patiently waited for the opportunity to move on to their destinations.

What began as a short, guilt-free delay quickly became an absolute nightmare.

One hundredplus extra people in a small town soon created multiple difficulties for the locals and the Great Northern crew. There wasnt quite enough food to feed everyone. Sanitation became a huge problem very fast. For drinking water, passengers were forced to quench their thirst with melted, dirty snow.

The passengers became irritated, restless, bored, and frustrated. For the Great Northern crew members, they became increasingly difficult to handle and keep calm.

Women prayed and cried. Men smoked and played cards. Children ran through the cars to pass the time. Crew members shoveled snow and worked on broken equipment. Telegraphers struggled with lines that were forever being cut off or, worse, torn down by slides.

The year 1910 would go down in history for some of the worst storms ever experienced in the mountains since 1897, when the Cascades supposedly received 140 feet of snow. This particular night, March 1, the strange weather brought rain, thunder, and lightning after a nine-day blizzard. The windows of the Pullman cars were soon covered up, and the passengers were entombed in a solid mass of snow.

Rev. James Thomson was on board and did what he could to help people. He also conducted a sermon Sunday night to help boost morale. All were singing and praying together for the storm to pass and for their safety from the snow cap high above the trains. Women wished they could wear mens clothing and risk walking out like a small group of men had done earlierdesperately making their way down to the safety of Scenica life-risking hike, but much better than being a sitting duck.

Just a few days earlier, at Cascade Tunnel Station, a slide tore down the mountain, destroying a beanery that had accommodated the same trains, taking with it the two cooks who so graciously fed and cared for the passengers before they were stranded at Wellington. The cook Harry Elliker and waiter John Bjerenson were killed instantly, and the beanery completely destroyed.

The passengers heard of this tragedy and became frantic; the avalanche escalated their fears. It was no secret to anyone that their trains had just moved from the exact spot where the avalanche occurred. It could have been they who were killed so quickly. They begged to be returned to the perceived safety of Cascade Tunnel.

But the crews and locals reassured the passengers that there had never been an avalanche in the spot where the trains were now parked. It was thought to be the safest location to remain until the storm passed. And as the crew pointed out, the tunnel was plagued by conditions that were dangerous and unsanitary. Passengers would be forced to trudge through mud all the way to the hotel twice a day for their food, a walk which several disabled passengers would be unable to make. Anyway, there was not enough coal to both move the trains and keep the cars heated. The trains would stay put.

So, the remaining passengers settled in for another long evening. The last lamp was turned off by the porter sometime before midnight, and all the cars were soon filled with snoring. Before they went to bed, many had made the decision to finally leave the stalled trains first thing in the morning, no matter what.

During the night, as the storm raged, the gigantic snow cap (rain-soaked now) was possibly struck by lightning, which loosened its grip from the steep mountain; practically in an instant, most everyone in the trains was dead, crushed by an enormous avalanche a half-mile long, a quarter-mile wide, and 14 feet thickapproximately 10 acres of snowkilling them within seconds.

Asking who was to blame is of no use now; what is done is done. Research proves that everyone concerned was working as hard as they could, performing the best they could, and providing safety for the passengers as well as they could. With snow falling sometimes at the rate of one foot per hour, it is amazing the crews were able to do anything productive at all.

Next page