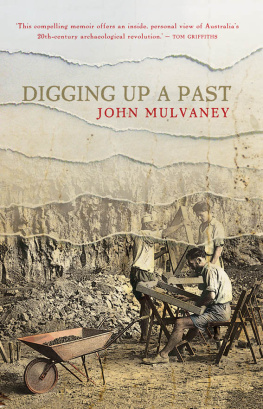

Justly described as the Father of Australian Archaeology, John Mulvaney, born in 1925, was the first university-trained prehistorian to make Australia his subject. He returned from World War II to study History, including the archaeology of Roman Britain, at the University of Melbourne. It convinced Mulvaney that Australia must also have a significant archaeological record.

Following retraining in archaeology at Cambridge, John went on to excavate Aboriginal occupation sites. His most famous achievement was his work in establishing the antiquity of Aboriginal occupation. In 1962 his dig at Kenniff Cave, in Queensland, proved that people inhabited Australia during Pleistocene (Ice Age) times. He wrote the first book to outline the Aboriginal past before 1788.

Thereafter his interests became more public. He was a Council member of the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies for 18 years. As an Australian Heritage Commissioner he was the chief Australian delegate to the UNESCO meeting in Paris which determined the criteria for World Heritage listing. He was a member of the 197475 Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections.

John was a prominent figure in bridging the gap between the public and the academy and campaigned on public issues: not least the struggle to save the Franklin River and its Aboriginal heritage. He has continued to write during his retirement.

DIGGING UP A PAST

John Mulvaney

For Jean

A UNSW Press book

Published by

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

www.unswpress.com.au

John Mulvaney 2011

First published 2011

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Mulvaney, D. J. (Derek John), 1925

Title: Digging up a past/John Mulvaney.

9781742232195

Subjects: Mulvaney, D.J. (Derek John), 1925

Archaeologists Australia - Biography.

Historians Australia - Biography.

Dewey Number: 930.1092

Digital conversion by Pindar NZ

FOREWORD

This humble and compelling memoir offers an inside, personal view of Australias 20th-century archaeological revolution. John Mulvaney is Australias most celebrated archaeologist. He is also a historian of great originality, tenacity and vision. This strong combination of curiosity about both documentary and material sources of the past produced a scholar who simultaneously sifted sedimentary and written evidence, who dug carefully in both field and archive. Mulvaney therefore became not only the archaeologist who took the Australian human past back into the Pleistocene, but also the pioneering historian of European curiosity about Aboriginal society. His scholarly humanism has had a strong public influence through his political activism on issues of conservation, museums, heritage, the environment and Aboriginal rights.

In the early and mid-20th century most Australians believed that Aboriginal people had occupied the continent for only a few thousand years, and some argued for an even briefer presence. And there was an assumption that Aboriginal culture had been unchanging and its environmental impact minimal. Australia has a settler history of resistance to the intimations of Aboriginal antiquity and adaptability. From first settlement, there was reluctance among colonists to acknowledge the depth of belonging of a people whose continent they had usurped. Investigating the Aboriginal past was mainly the province of amateur collectors who competitively scoured the country for stone tools and sometimes delivered them to museums by the truckload. They did not dig because they believed there would be nothing to find. And a good collector was someone who left very little for others to discover.

In the 1950s and 60s, these collectors began to refer warily to the new man. His name was John Mulvaney, now in his thirties and recently returned from his archaeological studies at Cambridge University. In England, John had found his romanticism stirred by encounters with the deep past, and in Britain, Europe and Libya he had experienced thrilling fieldwork. I hankered after the Iron Age, John later wrote, but knew I must return to Stone.

It is Mulvaneys name, above all, that we identify with the archaeological revelation that Australia has a Pleistocene past. No segment of the history of Homo sapiens, wrote John, had been so escalated since Darwin took time off the Mosaic standard. His archaeological career directly coincided with the radiocarbon revolution. Carbon-14 was a tool tailor-made for some professional magic. It was a scientific method of dating that bypassed the field typologies of the amateur and connoisseur and brought laboratory science into the heart of humanistic archaeology. The techniques of the nuclear age would decipher a stone age land; radiocarbon would illuminate what John called the dark continent of prehistory.

When Mulvaney returned home from Cambridge and began to introduce professional archaeological practice and perspectives to the study of ancient Aboriginal history, his instinct was to work respectfully with the white collectors and curators who had preceded him. Thus his double intellectual enterprise was launched: to apply objective scientific techniques to the chronology of ancient Australia, and at the same time to understand those who had previously studied or mediated the Aboriginal past, and whose work and ethics he often needed to criticise or transform. It is a key to Mulvaneys character, and a testimony to the sort of historian he is, that he has spent much of his life trying to understand the culture of collection that he helped to overturn. In evaluating this legacy he also hoped to free himself from it. In systematically digging the earth, in establishing human antiquity, in demonstrating cultural and environmental change over Australian time and space, and in championing the protection of Aboriginal sites and heritage, he upended the world of his predecessors.

Yet there were continuities that served him well. Like the collectors, Mulvaney was empirical in orientation, fieldwork-driven and fascinated by artefacts. Like them, he was accused of being too interested in stone technology. Mulvaneys common interests with the collectors, his commitment to cross-disciplinary partnerships in research, and his slightly delayed professional training made him a sensitive intermediary between amateur and professional at a critical time in Australian archaeology. In practice, he minimised his professional status, or used it to give recognition to the most rigorous of his predecessors in particular, Norman Tindale, Frederick McCarthy and Edmund Gill. Through his research, Mulvaney crusaded against the straitjacket of Social Darwinism that gripped Aboriginal studies for nearly a century, and this led him to become a deeply informed critic of evolutionary thinking. He considered racism a fatal flaw in the Australian psyche, and was keen to articulate a humanitarian tradition in Australia and a positive, moral vision of race relations. This powerful interest in the history of ideas about Aboriginal Australia enabled him to become a sympathetic biographer of intelligent men of the frontier Alfred Howitt, Collet Barker, Baldwin Spencer, Frank Gillen, Ernest Cowle, Patrick Byrne and Paddy Cahill. Mounted Constable Cowle and the telegraph official Pado Byrne were outback bushmen with legendary thirsts and Mulvaney, ever the archaeologist, found evidence of the drinking feats of his heroes in a trail of broken glass that you can still find out there today.