CHAPTER ONE

Home

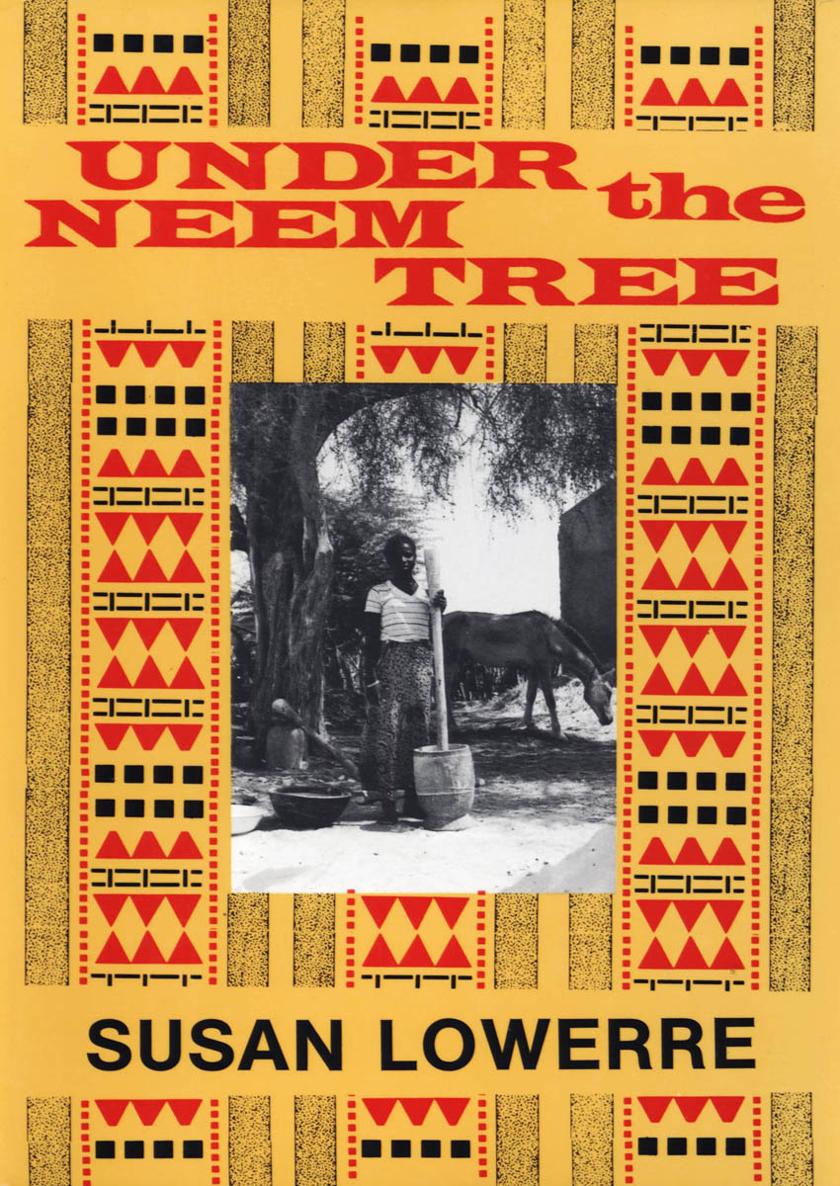

The Dou, a tributary of the Senegal River, flows inside its red-tan banks past a small village of clay houses with thatched roofs. This is Walli Jalla: a Pulaar village with neem trees and acacias, goats and donkeys and chickens, and the steady rhythm of women pounding millet in the mornings. In the evenings, when the light is soft, fishermen float on the river in dugout canoes, setting their nets against the setting sun. It is always the same, sunset after sunset, the men dipping their wooden paddles into the green water, cutting across the pink evening sky.

I used to like to sit and watch the fishermen, and think that someone might have sat on the bank a hundred or two hundred years before me, watching fishermen in their dugout canoes floating on the passing green water, their gill nets held just for a second like spider webs against the sun before being plunged down into the riverthe magical river which flowed between desert banks.

I would sit and watch until the sun was almost gone, and the bats had come out to swoop down over the glass-smooth water, and the mosquitoes woke up from their days rest. Then I would stand and rewrap my pagnea piece of cloth which Senegalese women traditionally wear wrapped around their waists like a skirtand walk the little path past the boutique, where they sold tea, sugar, and oil, winding between compound wallsthe Aans and the Sis, and the family who I never really got to know, but who invited me to drink tea with them one time when they were celebrating their daughters wedding. I would follow the path and it would lead me back home.

My compound was fancy with two clay houses covered over with plaster and whitewash, roofed with corrugated tin. It must have been something when it was first built, shining so white, like a diamond in the center of the brown village. I am not sure who it was built for, but it was owned by the marabout, a Moslem religious man, who lived in the village of Guia and owned a TV which he tried to run off a car battery. Maybe it had been his house, but now it was crumbling with time and the rains, and the plaster was chipped. One whole wall of the main house was bowed out, as though it was trying to lean over the compound wall to see what was on the other side. In places the red clay had broken through the plaster and run down the whitewash leaving behind stains that looked like tears of blood, and the green-painted doors had turned almost gray from age and neglect.

There had been Peace Corps volunteers before me who had lived in this house. Supposedly, no one else would rent it because they all believed it was haunted. I never saw the ghost, although there was a huge rat who lived in the locked-up house I did not use who made an awful lot of noise at night. Dirk named him Julius Caesar. The main house was haunted by five small bats who lived in the storage room, and a mouse, who had frequent visitors and I think later a whole family, and there were uncountable insects, but I never did see the ghost.

The inside wall of my compound was shared by the Diengs, my next-door neighbors. They would pop their heads over to see how I was doing, to greet me, or to tell me something was going on. I would pop my head over to see who was passing siesta in their compound, whether anyone was making tea, and to ask what was for dinnergosi or lacciri. Gosi is like cold rice pudding, only sometimes made with corn, and lacciri is steamed millet, which we usually ate with leaf sauce. I hated gosi. We ate it when the Diengs could not afford millet.

The Diengs adopted me. At first, I only knew them as the family of Aisata, the girl I paid to wash my clothes in the river and to bring me a bucket of the cool passing water each morning, which I kept in my house as a treasure against the heat of the day. I poured it into my loonde, a sphere made of clay which breathed, keeping the river water cool even when the air danced with the heat.

Aisata had taken the job because Fatu, who originally brought my water and also cooked my food, told me she had too many other things to do. Aisata was a teenager and wanted to know all about America and clothes and fashions and American men. Her body was just becoming a womans and she liked to prance at the rivers edge in her pagne, making me smile and think of when I had been sixteen. Sometimes Mbint or Fatiim and their children would come visit my compound with Aisata and they would hold my hands and exchange soft Pulaar greetings, or they would ask me to drink tea, or try to teach me new Pulaar words. Slowly the Diengs seeped into my life this way, a little at a time, an afternoon, a few words, a reflected smile.

I did not begin to know Samba, who became my village father, until one day after I had lived in Walli Jalla for half a year. That afternoon the village children taunted me beyond what I could endure and I decided to catch one and beat him. Aisata heard my anger and came to see what was wrong. She said I must speak to Samba, the old man of her compound.

I did not want to speak with anyone. I had been walking across the makeshift soccer field with Dirks dog Sahn, when the children collected into little clumps and ran after us chanting Sahn, Sahn, and threw sticks and stones at her, staying just out of reach, and poor Sahn shook with fear.

It was too much. Taunting the white woman was great fun. Sometimes the children threw stones at my house. It was the most entertaining of village games. If you could catch one of the children, then you could hit him, supposedly teaching him respect, and the rest would let you alone. I could never catch one.

Aisata must have seen in my face that this time I meant to catch one. She tugged on my arm and said again I must come to her compound; Samba would help me. I had never spoken to Samba before. I could just barely picture him as the elderly man with white hair who sat on his mat in the evenings working his prayer beads and listening to the Pulaar station on his transistor radio. Aisata would not stop until I said I would come.

We walked inside the Diengs compound walls, and Samba was sitting where he always seemed to sit, on his mat in front of the house he shared with his wife. His face was softly wrinkled, the color of warm earth touched by the evening sun. His hair was very white. I wondered how old he was, and how I could not have noticed him before. He seemed a living history, as though he had been given secrets to hold over time, like an old church, its wood shining from generations of hands.

He shook my hand and told me to sit and asked what bothered me. My Pulaar was not very good, but I spit out the words I knew with hatred and frustration, thinking of how the children had made Sahn, who would not hurt a thing, shake with fear and roll her soft brown eyes.

Samba watched me as I spoke. He was like the river, flowing, always flowing for so many years, surviving this world of dust and heat and disease the way the river survived its desert banks. He had seen so much. Any one point in time seemed small set before the patience in Sambas eyes. He soaked up my frustration and anger the way the river pulled away the heat of my body at the end of each day. He nodded his head at my words, saying quietly that the children were bad, he would talk to the elders of the village. He said I was a guest of his family in the village and he would not let anyone mistreat me.