DIARIES OF COURT LADIES OF OLD JAPAN

The Heian period (794-1186AD) of Japanese history the setting of The Tale of Genji - was an era of unsurpassed refinement in art and literature, in which women played a unique role. Dominated by the mighty Fujiwara clan, the Japanese court was the bright centre of a world in which rare and exquisite taste in poetry, art, calligraphy, dress, incense, colour, even the selection of gifts, was cultivated to an amazing degree. This gossamer veil of beauty masked another reality of political intrigue and passionate rivalries which intensified the heady atmosphere of a court in which flirtations and love affairs were endemic. Cultivated and artistic women held a privileged position at court, and they perfected the literary genre of diaries that combined subtlety, strength and starkness in their depictions of life in this enclosed and dream-like world. These diaries are among the jewels of Japanese literature and three are presented here The Sarashina Diary, the Diary of Izumi Shikibu and the Diary of Murasaki Shikibu with an introduction by the poet Amy Lowell, an early admirer of Japanese literature.

The Authors

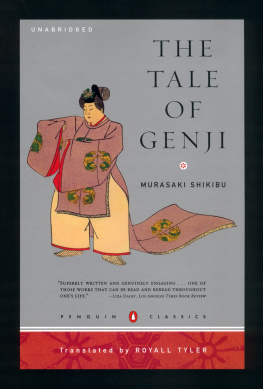

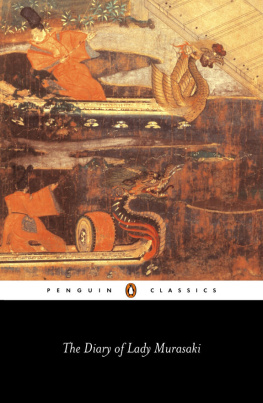

The name of the author of the Sarashina Diary is unknown, but she was the daughter of Fujiwara no Takasue, and was born around 1009AD. Izumi Shikibu was born around 976AD, served at the court of the Empress Akiko and married Fujiwara no Yasimasu. Murasaki Shikibu, born around 973AD, was the daughter of Fujiwara Tametoki and the wife and then widow of Fujiwara no Nobutaka. A lady-in-waiting to Empress Akiko, she was also the author of the great epic Tale of Genji, considered by many to be the first modern novel.

(For explanation see List of Illustrations)

DIARIES OF COURT LADIES OF OLD JAPAN

TRANSLATED BY

ANNIE SHEPLEY OMORI

AND

KOCHI DOI

Late Professor in the Imperial University, Tokyo

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

AMY LOWELL

First published in 2005 by

Kegan Paul International

This edition first published in 2010 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2005

Transferred to Digital Printing 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-1089-7 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-1089-7 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

TRANSLATORS NOTE

THE poems in the text, slight and occasional as they are, depending often for their charm on plays upon words of two meanings, or on the suggestions conveyed to the Japanese mind by a single word, have presented problems of great difficulty to the translators, not perfectly overcome.

Izumi Shikibus Diary is written with extreme delicacy of treatment. English words and thought seem too downright a medium into which to render these evanescent, half-expressed sentences and poems vague as the misty mountain scenery of her country, with no pronouns at all, and without verb inflections. The shy reserve of the ladys written record has induced the use of the third person as the best means of suggesting it.

Of the Sarashina Diary there exist a few manuscript copies, and three or four publications of the text. Some of them are confused and unreadably incoherent. The present translation was done by comparing all the texts accessible, and is especially founded on the connected text by Mr. Sakine, professor of the Girls Higher Normal School, Tokio, published by Meiji Shoin, Itchome Nishiki-cho, Kanda-ku, Tokio. As far as possible the exact meaning has been adhered to, and the words chosen to express it have been kept absolutely simple, without complexity of thought, for such is the vocabulary in which it was written. Sometimes the diarist uses the present tense, sometimes the text seems reminiscent. The words in square brackets have been inserted by the translators to complete the sense in English of sentences which literally rendered do not carry with them the suggestion of the Japanese text.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

COURT LADYS FULL DRESS IN THE HEIAN PERIOD

From Kokushi Daijiten, by kind permission of Mr. H. Yoshikawa. The figure was drawn for the purpose of showing the details of dress and therefore gives no indication of the grace and elegance of the costume as worn. It shows the red karaginu, or over-garment; the dark-green robe trimmed with folds, called the uchigi; the saishi, or head-ornament, in this case of gold but sometimes of silver; the unlined under-garment of thin silk; the red hakama, or divided skirt; and the train of white silk painted or stained in colors.

From an old book.

From Kokushi Daijiten, by kind permission of Mr. H. Yoshikawa. The figure shows the zui, or ornament of the head-strap holding the head-dress in place; also the method of rolling up the gauze flap of the head-dress. Tucked into the red state coat appear a half-spread fan and some folded sheets of paper, and at the back is seen a quiver made of lacquered wood. Underneath the red coat the hakama is shown. The shoes are of Chinese pattern.

From old prints.

From a print in an old book.

INTRODUCTION

BY AMY LOWELL

THE Japanese have a convenient method of calling their historical periods by the names of the places which were the seats of government while they lasted. The first of these epochs of real importance is the Nara Period, which began A.D. 710 and endured until 794; all before that may be classed as archaic. Previous to the Nara Period, the Japanese had been a semi-nomadic race. As each successive Mikado came to the throne, he built himself a new palace, and founded a new capital; there had been more than sixty capitals before the Nara Period. Such shifting was not conducive to the development of literature and the arts, and it was not until a permanent government was established at Nara that these began to flourish. This is scarcely the place to trace the history of Japanese literature, but fully to understand these charming Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan, it is necessary to know a little of the world they lived in, to be able to feel their atmosphere and recognize their allusions.