Copyright 2012 by Eric Fischl

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fischl, Eric, 1948

Bad boy / Eric Fischl and Michael Stone.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Fischl, Eric, 1948 2. PaintersUnited StatesBiography.

I. Stone, Michael. II. Title.

ND 237. F 434 A 2 2012

759.13dc23

[ B ] 2012038226

eISBN: 978-0-7704-3558-5

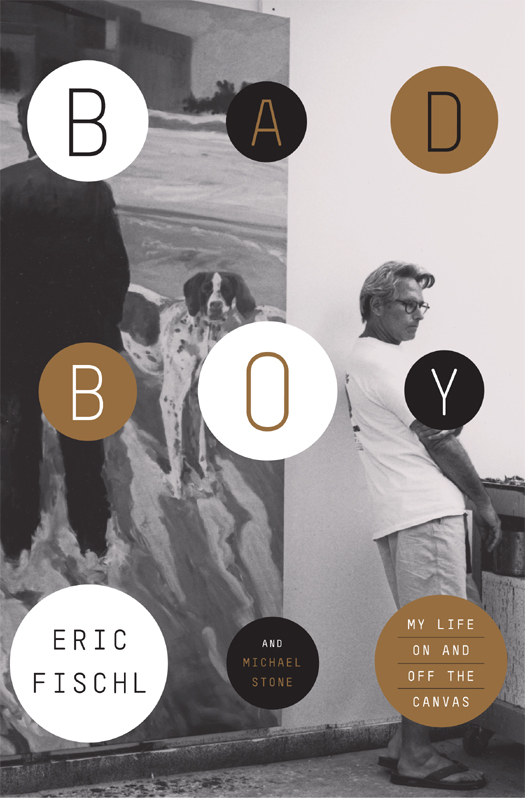

Jacket design by Christopher Brand

Jacket photograph by Grard Rondeau, 1993; early version of A View from the Shallows Eric Fischl

v3.1

For my father, who stayed and did whatever was

necessary to make sure we would be okay.

ERIC FISCHL

For Fiona

MICHAEL STONE

CONTENTS

MR. LAUGHTER

SPRING 1986

T HE vanity plate on the bumper of his beige Caddy identified him as Mr. Laughter. But I didnt notice that detail at first, and anyway, there was nothing funny about Mr. Laughter. Hed been riding my rear end for several blocks, flashing his lights, honking, and nudging my fender. What the hell did he want? Even at this hourten P.M. on a weekday eveningthe crosstown traffic was hardly moving. There was no place to go.

Pull over, my girlfriend, April, seated beside me in our dowdy VW wagon, said.

We were on our way home from a dinner in my honor. That night had been the opening of my retrospectiveactually a survey of my early workat the Whitney. Or maybe it was a preview. I dont remember. Id been drinking steadily since four P.M. Jack Daniels, wine, Armagnac chased down with lines of cocaine. I was blasted. Everything that happened that evening until my encounter with Mr. Laughter was a blur. What should have been the most memorable night of my professional life had already become a black hole.

It wouldnt be hard, though, to piece together the evening at the Whitney. The show covered the museums entire third floortwenty or thirty of my early psychosexual suburban paintings, including Sleepwalker and Bad Boy. I would have camped myself at the periphery of the room, my face sore from the obligatory smiling, saying thank you, thank you, to a nonstop stream of well-wishers. They would have been part of an eighties mixed-bag art crowd identifiable by their uniformsa few old-timers, trickle-downs from the Alex Katz opening on the floor above mine, dressed in threadbare jackets and ties; Carl Andre and Chuck Close types who were big into workmanlike costumes; the downtown seventies holdovers in jeans and scrubby tees; the current crop of rock-star artists who embraced the fusion of art and fashion in their Armani suits and silk tees; Wall Street denizens, media and real estate collectors in tailored business suits, their wives in designer frocks; gallery girls in their little black dresses; and a raft of actors, models, It-girls, and eccentrics in feathers, scarves, and pirate outfits.

I had on one of those shapeless Italian jackets, something that would have been lost on Mr. Laughter but that I hoped would appeal to the different strata of the crowdhip, casual, affecting a confident indifference. The retrospective was a great honor, of course, but not one I felt sure I deserved. Whats more, any retrospectiveeven one based on just five years of paintingdraws a line around your work, defines you as a certain kind of artist, creates expectations among your patrons and followers that make it difficult later for you to break outside the boundaries of your comfort zone.

But there wouldnt have been much talk about art this evening. Openings arent the time or place, and even in the most intimate settings, collectors rarely ask me about my paintings. At most, theyd have told me what they owned and their plans for their collections. And then periodically Id have escaped to the ground-floor bardrinks werent allowed in the galleriesor hit the mens room to freshen up my high.

B EHIND Lincoln Center, I felt something jostling against my fender, pushing me out into the intersection, and I stepped on the accelerator. Mr. Laughter did too. The Caddys windshield ballooned in my rearview mirror and the slow downs and let him passes inside the VW became more vehementuntil I snapped. I rarely initiate confrontation. But when it finds me, I hunker down. As I made the left onto West End, Mr. Laughter pulled out to pass me and I swerved right and left, blocking his efforts.

Are you crazy? April shouted. He could have a gun.

Actually, given the circumstances, I wouldnt have been surprised if he did have a gun. I was scared out of my mind. But I was also imploding with rage. And there was yet another part of mea kind of professional detachmenttaking in the whole scene with a mixture of wonder and bemusement. Or maybe it was the alcohol and cocaine talking.

Halfway down the block I spotted a couple of cops on the uptown side of the street patting down some guy. I hit the brakes, made a U-turn, and parked alongside them. April implored me to stay in the car. Much to my surprise, Mr. Laughter had angled his Caddy into the spot next to mine. Now he chased after me as I scrambled over to the nearest officer.

This guys mad, I yelled. Hes trying to kill me!

Hes nuts, my would-be assassin rejoined. Hes driving like an idiot!

One of the cops got between us. You could tell he wasnt happy being interrupted in the middle of an arrest. But he let us vent, hoping, I guess, it would defuse the situation.

Do you know who I am? Mr. Laughter barked at me. Do you know who youre fucking with? I was suddenly curious. He was short, barrel-chested, and permatanned, with gelled, wavy jet-black hair. He wore a cream-colored double-knit suit, an open-necked dress shirt with one of those wide, oversize collars, and a barrage of gold rings on either hand. Maybe he was a mobsteror an Atlantic City entertainer of some kind.

It was at that moment, in the middle of us screaming at each other, that I first noticed the lettering on his vanity plate. Meanwhile Mr. Laughter kept telling the cop and me that he was some kind of big shot. Looking at my scruffy car, downtown attire, and soft, bespectacled features, Mr. Laughter told me, Youre a nobody. A big fuckin nobody.

L ATER I thought the whole thing was pretty funny. There was the irony of the situationmy encounter with Mr. Laughter wasnt the least bit humorous. Then there was the business of him calling me a nobody. I was experiencing my fifteen minutes of fame, wrestling with a celebrity that I neither trusted nor felt Id earned. My income was making me rich beyond my dreams. Vanity Fair had run a generous six-page feature on me. And now the premier museum of American art was giving me a retrospective.

I wasnt worried about being a nobody, but about what kind of somebody I was, where I fit in with my more successful peers. I wanted my work accepted and compared to the work of the best painters of my generation. Two years earlier Id joined the Mary Boone Gallery so Id be viewed in the context of my contemporariesJulian Schnabel (who left for Pace shortly after), David Salle, Ross Bleckner, and the somewhat older Germans Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, and Sigmar Polke. I wanted to spark a conversation between my paintings and theirs. I wanted to be relevantor, as Mr. Laughter might have put it, a somebody.