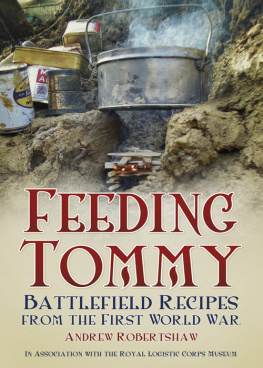

This book is dedicated to the memory of army cooks such as Private G/12022 Abel Flitney, who died of wounds in the Battle of Passchendaele on 2 August 1917, and to all cooks who served and made the supreme sacrifice in the Great War.

C ONTENTS

FOR MANY PEOPLE rations in the Great War have been summed up by a conversation in the famous television series Blackadder Goes Forth, which ran from 1983 to 1989. When Captain Edmund Blackadder, who is serving in the trenches of the First World War, asks what there is to eat, his soldier servant, Private Baldrick, replies:

Private Baldrick: Rat au Van, Sir.

Captain Blackadder: Rat au Van, Baldrick?

Private Baldrick: Yes Sir, its rat thats been

Captain Blackadder: Run over by a van.

Without wishing to dismiss in any way the humour of the piece, the fact that the Blackadder Goes Forth series is now included as a source in the curriculum about the First World War indicates that this exchange represents a common view of trench rations. A quick survey of resources for schools on the Internet produced the following (the emphasis is my own):

By the time the food reached the frontline it was always cold.

Eventually the army moved the field kitchens closer to the frontline but they were never able to get close enough to provide regular hot food for the men.

Men claimed that although the officers were well-fed the men in the trenches were treated appallingly.

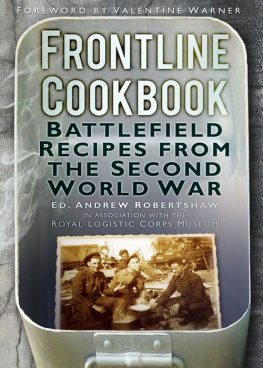

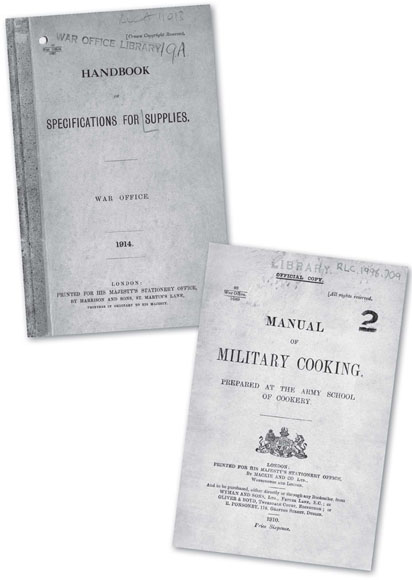

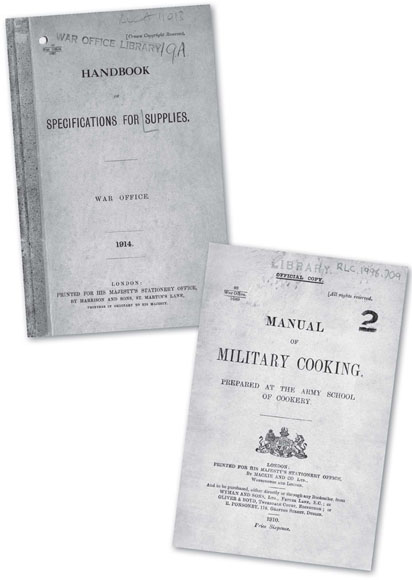

I am grateful for the opportunity to present the reality based on the archives of The Royal Logistic Corps Museum and a range of contemporary accounts by the men who cooked the rations and ate them between 1914 and 1918. This book is interspersed with hints and tips that they learnt during service and their recipes, kindly reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of The Royal Logistic Corps Museum.

I would like to express my thanks to the many army chefs, as they are now called, who have supported The Royal Logistic Corps Museum and myself with this project.

WHETHER IT IS a memorable meal when out of the trenches or the failure of the rations to arrive on a cold wet morning in the frontline, descriptions of life on the Western Front are littered with references to food. To those who read the accounts, soldiers appear obsessed by food. Whether soldiers are in the frontline as infantrymen, serving the guns, driving vehicles or caring for animals, they need to eat. Even if the men who had been civilians before the war and now found themselves in the ranks had not always eaten adequate meals in civil life, they expected to be paid for their military service and to receive three square meals a day. Many of the recruits of 1914 enlisted to get new clothes on their backs, rations to eat, regular pay and to do their bit. For many in a world before the welfare state, and at the time of an economic recession, the imperative of food and the promise of meals, not love of King and Country, brought them to the recruiting office. It was noticed by many instructors and officers that recruits rapidly filled out. Younger ones even put on stature as a response to the rations they received, combined with exercise and unaccustomed physical activity.

Soldiers are often young men, who are both growing and involved in strenuous activity. In consequence, they are frequently constantly hungry and sometimes looking for comfort in what can be a bleak environment with little other opportunity for enjoyment. A soldier serving as a transport driver with the London Rifle Brigade states in his memoir:

It was a curious thing that when food was in abundance, as on lines of communication, we did not possess enormous appetites; but when we had half-slices of bread, estimating we couldnt eat more now because we should have to want a little for the next meal we seemed suddenly to have a craving for twice as much as we normally ate.

If older soldiers were not so hungry, they appear to search for food that is familiar and reminds them of home; this, potentially, provides a break from the tedium of military rations, in which the diner has no choice of menu. Whether it was the pure satisfaction of eating or the search for variety that compelled soldiers, they all knew that meals were critical. This was recognised by the army and throughout the war the military authorities did all that could be done to ensure adequate and well-cooked rations were available. Hungry men make bad soldiers, hence the axiom attributed to Napoleon: An Army marches on its stomach.

Although the Great War of popular imagination has soldiers constantly underfed and virtually begging for food, the reality is rather different. In the autumn of 1914, Private Frank Richards records:

There was no such things as cooked food or hot tea at this stage of the war, and the rations were very scarce, we were lucky if we got our four biscuits a man daily, a pound tin of bully between two, a tin of jam between six and the rum ration which was about a tablespoon and a half.

This describes the early phase of trench warfare before the supply chain to the United Kingdom and Empire was fully established and before local purchase became common. Despite these advances, there could be local problems during periods of shelling, combat or movement of units. Private Beatson recalled an occasion in the trenches when there was no food at all: The following day we had no rations sent us, our emergencies were done, and the men went hungry.

George Coppard provides a balance of attitude towards the matter of rations. Out of the frontline his view was that, The cooking arrangements were good too. Burgoo (porridge) before the breakfast fry-up, and spotted dog (currant pudding) with dinner, were welcome fillers. However, conditions in the frontline were a contrast:

Sharing out the rations for a small unit was a bit of a lottery, especially where tins of jam, bully beef, pork and beans, butter and so on were concerned. The share-out was seldom favourable to a six-man team. So far as I know there were no hard and fast rules regarding the quantity of each type of ration a man was entitled to. The Army Service Corps [ASC] were the main distributors, but how much food actually arrived in the trenches depended on such things as transport, the weather and enemy action. Irregular appropriations were likely to be made en route.

Even when the rations arrived, they could present problems of sharing them out in a fair manner:

Presently our acting QMS [Quartermaster Sergeant] arrived with a sack, which was hauled up into the loft with some difficulty, and proceeded to issue out the rations according to messes. The average number in a mess was four, but some parties drew for two, some for three, others for five; here and there one single man clamoured for his proportion and, in desperation, Hurford brigadied two or three irreconcilables together and treated them as a mess, regardless of their feelings. The difficulty of splitting up cheese, tins of margarine, jam etc., among such varying quantities can be imagined.

He contrasts this somewhat mixed experience with an account of a chance encounter with an army cook. When making his way down a communication trench to join his unit, the young soldier had a very pleasant surprise:

I found to my delight that I had stumbled across a kind of soup kitchen. The Tommy in charge was stirring a copperful of Shackles (soup made from the very dregs of army cooking and stirred with a stick). I must have looked in need of extra nourishment for he said Dyer want a drop, son? Yes please, I replied, if you can spare it. The warmth and zest from that beefy liquid, unexpected as it was, compelled me to accept a second bowlful which I drank with the same enthusiasm as the first.

Next page