Contents

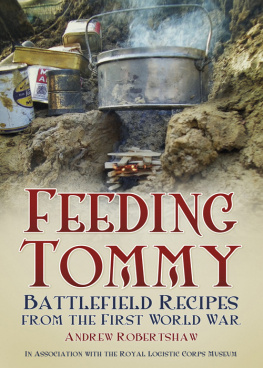

MILITARY HISTORY IS littered with defeats caused by a broken food supply chain or troops made to march too far on an empty stomach.

Andrew Robertshaws Frontline Cookbook is a fascinating insight into the logistics of feeding an army, an account of how innovation and imagination produced essential solutions to combat starvation as no matter how many weapons an armed force may carry, without food neither can be used to best effect.

As a chef I have found feeding just a few strenuous at times, so just imagine how to approach feeding hundreds of thousands of troops spread across the globe in thick jungle, bone-cracking cold or the searing desert heat.

Covering such subjects as equipment, rationing, training and location, Andrews knowledge is second to none and the well-illustrated, recipe-plump writing makes Frontline Cookbook informative reading for not only those with an interest in military history, but anyone interested in food and human endeavour.

Valentine Warner, 2012

Part One

An Army Marches

on its Stomach

Frontline Food before

the Second World War

THE QUOTATION THAT an army marches on its stomach has been attributed to both Napoleon Bonaparte and Frederick the Great. What matters is not who made the original statement but that it demonstrates that two of the worlds great military commanders clearly understood the connection between feeding an army and its ability to fight. Although it is commonly appreciated that soldiers need ammunition, and more recently fuel for their vehicles, they have always needed something to eat and drink, whether on the march or in camp. Soldiers can survive without ammunition but not without food and water. The Chief Minister to Louis XIV noted that neglect of supply and organisation could frustrate military operations. He states that history knows more armies ruined by want and disorder than by the efforts of their enemies. the requirement of armies to remain stationary for weeks or months at a time. Despite acts of terror intended to force the unarmed farmers and labourers to provide the French troops with food, resistance increased as the armies drove the population to the verge of starvation. Rather than comply with the invaders, civilians hid their stocks of food and animals, and then began to systematically hunt down and kill the French soldiers and their wives who had been sent in search of provisions. This created the first Guerrilla war and was largely responsibly for allowing Wellingtons numerically inferior army to tie down Napoleons forces in what became known as the Spanish Ulcer. Wellington did not suffer from the same problems as Napoleon because he was both regarded as an ally by the local populace and his quartermasters paid for supplies they required.

Supplying armies with food has provided a number of terms which are still familiar today. Although rationing is associated with restricted supply to civilians on the Home Front in the Second World War, a ration was originally a quota of food and drink provided for soldiers and sailors as part of their service. Originally, rations consisted of the provision of a few basic, staple items, normally meat, fresh or preserved (salted); bread or biscuit and a liquid that was safe to drink, unlike the water, such as beer or wine. The actual amount of these staples varied over time and was normally supplemented with privately purchased food items such as vegetables, preservatives and flavourings. Because individual cooking is time consuming and wasteful of fuel, larger medieval households used a form of mass catering in which a group of people were provided with a set amount of prepared food which they shared amongst themselves. These groups were known as a Mess and the term was then adopted by both sailors and soldiers. This gives us expressions such as messmate, messdeck and Officers and Sergeants Mess. It is worth noting that these messes were formed of groups of around ten or twelve people and this continues to be reflected in military organisations as the file, squad or section. These reflect both the communal nature of eating and the need to organise armies into regular-sized military sub-units.

It was recognised that although some soldiers were accompanied by their wives on campaign, the so-called camp-followers, many were not and their cooking skills could range from poor to diabolical. In consequence, the role of Sutler was created to manage the procurement of rations and their cooking, making a profit on both transactions as they provided less cooked food than raw materials. As the Sutler was often a relative or agent to commanding officers, the system was open to abuse and the soldiers diet and health could suffer in consequence. However, in 1680 the English garrison of Tangier in North Africa

During Marlboroughs campaigns (170410), it was ordered that men should mess regularly and that they should have bacon or other fresh meat twice a week, the cost of which was to be met by stoppages from the soldiers pay. Parties of troops were sent out to gather root vegetables, although the Sutlers could always provide something better. Regulations required commanding officers to encourage butchers to follow their regiments with good stocks of butchered meat, and cattle on the hoof. It was these arrangements which the Duke of Marlborough had in mind when he stated that No soldier can fight unless he is properly fed on beef and beer. Its worth adding that at one point the English garrison of Elizabethan Dublin threatened to mutiny because they were being supplied with too much salmon and too many oysters, when what they really wanted was beef and beer!

As has already been noted, Wellingtons preparation for the campaign in the Peninsula included the development of a working Commissariat, responsible for the supply of provisions for the forces, but this does not mean that this was easy or that the Treasury in Whitehall were happy with the additional expense. One problem was that on the outset of the operations the Commissaries were mostly inexperienced and they had a skeleton staff to superintend the supplies to all units. At this time rations were issued by the Commissariat in the evening, usually for three days at a time. One days ration was issued to the men, the others were held at a regimental headquarters. In Spain in 1813, every soldier was entitled to a daily ration of a pound of meat, a pound of biscuit (or 112 pound of bread), and a quart of beer (or a pint of wine or 13 pint of spirits). When the army halted, ovens were built so that bread could be baked and meat obtained from butchered cattle which had been driven along behind the marching columns. The meat was usually boiled by small messes of soldiers in a communal pot to which was added pulses and vegetables. This provided a soup for the evening and a joint of cooked meat which could be eaten cold the next day. It was during the Peninsula War that British soldiers first received a standard issue individual cooking vessel called, not surprisingly, the mess-tin. This was a two-part tin-plated steel item, roughly D-shaped, to fit against the body or pack, and provided with a handle so it could be held over a fire or used as an eating vessel. It was far from ideal as too much heat would cause the tin plate to melt and soldiers cooking for themselves used vastly more fuel than communal cookery. However, the ability to make tea, and in some cases coffee, was recognised as a valuable contribution to the soldiers diet.

In the period after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, greater importance had been attached to feeding the army and the construction of barracks throughout the country meant that it was easy to superintend the feeding of troops. Previously they had been quartered on willing civilians or in public houses where they were supplied by the residents at the governments expense. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the soldiers ration at home comprised 1lb of bread and 34 pound of meat daily for this food, 6d per day was stopped from his pay cooking facilities were available in the new barracks, but they were of a very basic character. The cooking utensils available to each company were two coppers (cooking pots), one for potatoes and the other for meat, which was always boiled as no ovens were available for roasting or baking, and so the solider had to put up with the eternal boiled beef and beef broth served hot, or cold meat at his two meals per day 7.30am breakfast and 12.30pm dinner after which he was without food unless he was able to purchase something to sustain him for the next nineteen hours. Although this might seem surprising to modern diners, it was clearly perfectly acceptable at the time and an order for the army issued by the Adjutant Generals Office dated 1 January 1882 makes it clear that the system was carefully regulated: