Copyright 2008 by Martin Dugard

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

First eBook Edition: May 2008

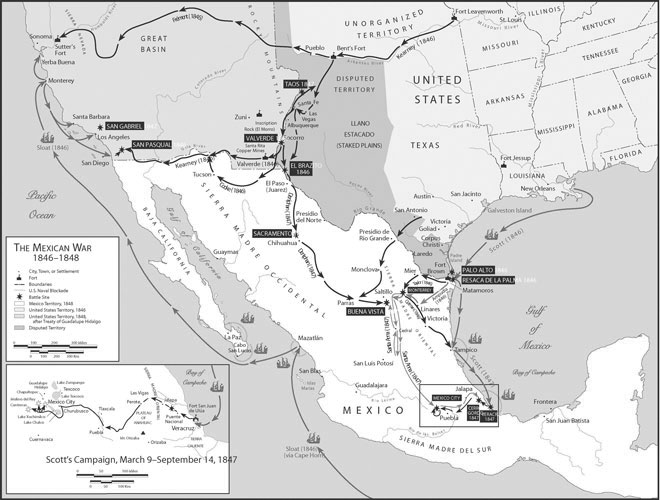

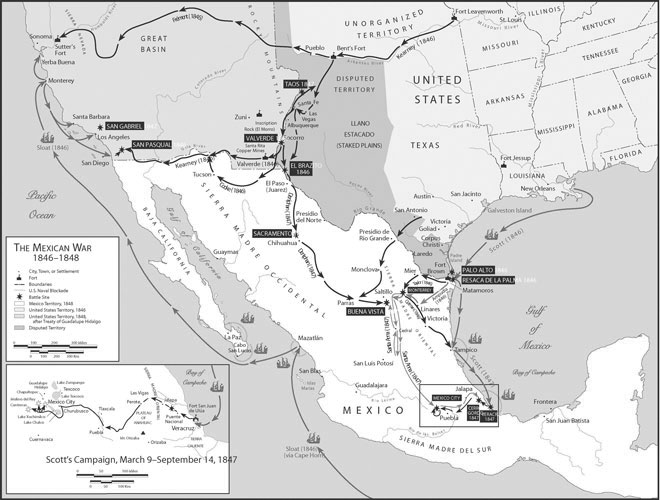

Maps by George Ward

ISBN: 978-0-316-03253-7

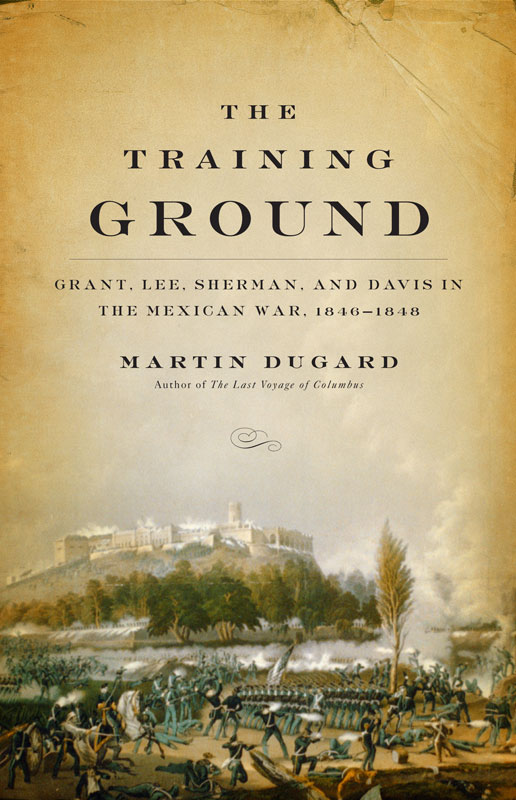

ALSO BY MARTIN DUGARD

Chasing Lance

The Last Voyage of Columbus

Into Africa

Farther Than Any Man

Knockdown

Surviving the Toughest Race on Earth

FOR COLONEL GEORGE ALAN DUGARD

T his is not a history of the Mexican War. Rather, it is the very personal story of the young men of West Point, marching into battle for the first time, learning well the rules and tactics of engagement.

I have always been fascinated by the theme of potential, and that thematic thread weaves through my body of work. How and why individuals blossom from rather ordinary citizens into world-changing historical figures, fulfilling their innate potential even as others around them wither or let their talents lie fallow, makes for powerful narrative.

The story you are about to read is the most poignant example of potential I have yet encountered. While researching, I was struck time and again by the way a group of regular young men were transformed by their experiences under fire, and how those experiences molded them into the great generals and statesmen they would one day become. Through their letters, memoirs, and personal histories, these figures became very much alive to me. I came to understand how intimately they knew one another from their years at West Point and then on the battlefields of Mexico. It was only when I finished writing about their Mexican War experiences that I allowed myself to read the rest of the story and look a dozen or so years down the road to the Civil War. It was thrilling to see how this brotherhood had shown the extent of their potential during the great campaigns of the Mexican War, but it was also heartbreaking to realize that these characters whom I had come to know so well would later become so devoted to killing one another. They were not dispassionate men. One can only imagine how gut wrenching it must have been to peer across a Civil War battlefield and remember the brotherhood once shared with the opposing general. The fact that many of these men resumed their friendships once that war ended is testimony to the enduring bonds forged at West Point and in Mexico.

Martin Dugard

Rancho Santa Margarita, California

January 2008

I t was Palm Sunday, 1865, when General Robert E. Lee rode forth to surrender. The brilliant Confederate tactician had struggled with the decision for two days, but now the time had come. His vaunted Army of Northern Virginia, which had bewildered and frustrated its Union opponents throughout the Civil War, was camped just outside the village of Appomattox Courthouse, hemmed in on three sides by a sixty-thousand-strong Union force. Rather than try to fight his way out once more, Lee had chosen to avoid further bloodshed. It was time for the war that had divided America to come to an end.

The home of a man named Wilmer McLean was chosen, somewhat randomly, as the site where Lee would meet with the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant to lay down his sword. McLean had once lived near the battlefield of Manassas, but a shell had burst through one of his windows during the wars opening battle, and he had moved to get away from the hostilities. Now, by mere coincidence, the war had found him once again.

Lee arrived first, resplendent in polished black boots, a pressed gray uniform, an expensive ceremonial sword, and a clean yellow sash. With him were Colonel Orville Babcock and Major Charles Marshall. Lee was a stately man who had been a soldier his entire adult life. To show up for such a momentous ceremony in a uniform that was less than his very best would have been unthinkable, even on this heartbreaking occasion.

The three men sat quietly in McLeans parlor, listening for the telltale rumble of approaching hoofbeats. An orderly had been directed to stand out on the road and direct Grant toward the house.

A half hour later, at 1:30 in the afternoon, the Union general trudged up the front steps. He had ridden thirty-five miles through April mud to be there and was clad in spattered boots and a privates uniform, onto which he had pinned shoulder boards displaying the three stars of a lieutenant general. He wore no sword, sash, or sidearm, and one of his coat buttons was in the wrong hole. Grant, noted one of his staff, Colonel Amos Webster, covered with mud in an old faded uniform, looked like a fly on a shoulder of beef.

It was not the first time the two great generals had come face-to-face. Grant later told friends that as he walked up those steps to accept Lees unconditional surrender, he felt a sudden embarrassment. Grant was fearful Lee would think his appearance was retribution for a long-ago rebuke during the Mexican War.

I met you once before, General Lee, Grant began as they made their introductions, while we were serving in Mexico, when you came over from General Scotts headquarters to visit Garlands brigade, to which I then belonged. I have always remembered your appearance, and I think I should have recognized you anywhere.

Yes, Lee replied cordially, setting Grant at ease. I know I met you on that occasion, and I have often thought of it and tried to recollect how you looked, but I have never recalled a single feature.

The two old soldiers sat down facing each other. Then, for the next few minutes, before getting down to the business of bringing to a close the most horrific war in U.S. history, Grant and Lee spoke of Mexico, where they had both worn blue, and where they first learned how to fight.

Texas was originally a state belonging to the Republic of Mexico. It extended from the Sabine River on the east to the Rio Grande on the west, and from the Gulf of Mexico on the south and east to the territory of the United States and New Mexico another Mexican state at that time on the north and west. An empire in territory, it had but a very sparse population, until settled by the Americans who had received authority from Mexico to colonize. These colonists paid very little attention to the supreme government, and introduced slavery into the state almost from the start, though the constitution of Mexico did not, nor does it now, sanction that institution. Soon they set up an independent government of their own, and war existed, between Texas and Mexico, in name from that time until 1836, when active hostilities very nearly ceased upon the capture of Santa Anna, the Mexican president. Before long, however, the same people who with the permission of Mexico had colonized Texas, and afterwards set up slavery there, and then seceded as soon as they felt strong enough to do so offered themselves and the State to the United States, and in 1845 their offer was accepted. The occupation, separation, and annexation were, from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.

Even if the annexation itself could be justified, the manner in which the subsequent war was forced upon Mexico cannot.

ULYSSES S. GRANT, MEMOIRS