California, ca. 195665

ONE

OFF DIAMOND HEAD

Honolulu, 196667

I HAD NEVER THOUGHT OF MYSELF AS A SHELTERED CHILD. S TILL, Kaimuki Intermediate School was a shock. We had just moved to Honolulu, I was in the eighth grade, and most of my new schoolmates were drug addicts, glue sniffers, and hoodsor so I wrote to a friend back in Los Angeles. That wasnt true. What was true was that haoles (white people; I was one of them) were a tiny and unpopular minority at Kaimuki. The natives, as I called them, seemed to dislike us particularly. This was unnerving because many of the Hawaiians were, for junior-high kids, alarmingly large, and the word was that they liked to fight. Orientalsagain, my terminologywere the schools biggest ethnic group. In those first weeks I didnt distinguish between Japanese and Chinese and Korean kidsthey were all Orientals to me. Nor did I note the existence of other important tribes, such as the Filipinos, the Samoans, or the Portuguese (not considered haole), let alone all the kids of mixed ethnic background. I probably even thought the big guy in wood shop who immediately took a sadistic interest in me was Hawaiian.

He wore shiny black shoes with long sharp toes, tight pants, and bright flowered shirts. His kinky hair was cut in a pompadour, and he looked like he had been shaving since birth. He rarely spoke, and then only in a pidgin unintelligible to me. He was some kind of junior mobster, clearly years behind his original class, just biding his time until he could drop out. His name was FreitasI never heard a first namebut he didnt seem to be related to the Freitas clan, a vast family with a number of rambunctious boys at Kaimuki Intermediate. The stiletto-toed Freitas studied me frankly for a few days, making me increasingly nervous, and then began to conduct little assaults on my self-possession, softly bumping my elbow, for example, while I concentrated over a saw cut on my half-built shoe-shine box.

I was too scared to say anything, and he never said a word to me. That seemed to be part of the fun. Then he settled on a crude but ingenious amusement to pass those periods when we had to sit in chairs in the classroom part of the shop. He would sit behind me and, whenever the teacher had his back turned, would hit me on the head with a two-by-four. Bonk... bonk... bonk, a nice steady rhythm, always with enough of a pause between blows to allow me brief hope that there might not be another. I couldnt understand why the teacher didnt hear all these unauthorized, resonating clonks. They were loud enough to attract the attention of our classmates, who seemed to find Freitass little ritual fascinating. Inside my head the blows were, of course, bone-rattling explosions. Freitas used a fairly long boardfive or six feetand he never hit too hard, which allowed him to pound away to his hearts content without leaving marks, and to do it from a certain rarefied, even meditative distance, which added, I imagine, to the fascination of the performance.

I wonder if, had some other kid been targeted, I would have been as passive as my classmates were. Probably so. The teacher was off in his own world, worried only about his table saws. I did nothing in my own defense. While I eventually understood that Freitas wasnt Hawaiian, I must have figured I just had to take the abuse. I was, after all, skinny and haole and had no friends.

My parents had sent me to Kaimuki Intermediate, I later decided, under a misconception. This was 1966, and the California public school system, particularly in the middle-class suburbs where we had lived, was among the nations best. The families we knew never considered private schools for their kids. Hawaiis public schools were another matterimpoverished, mired in colonial, plantation, and mission traditions, miles below the American average academically.

You would not have known that, though, from the elementary school my younger siblings attended. (Kevin was nine, Colleen seven. Michael was three and, in that pre-preschool era, still exempt from formal education.) We had rented a house on the edge of a wealthy neighborhood called Kahala, and Kahala Elementary was a well-funded little haven of progressive education. Except for the fact that the children were allowed to go to school barefootan astonishing piece of tropical permissiveness, we thoughtKahala Elementary could have been in a genteel precinct of Santa Monica. Tellingly, however, Kahala had no junior high. That was because every family in the area that could possibly manage it sent its kids to the private secondary schools that have for generations educated Honolulus (and much of the rest of Hawaiis) middle class, along with its rich folk.

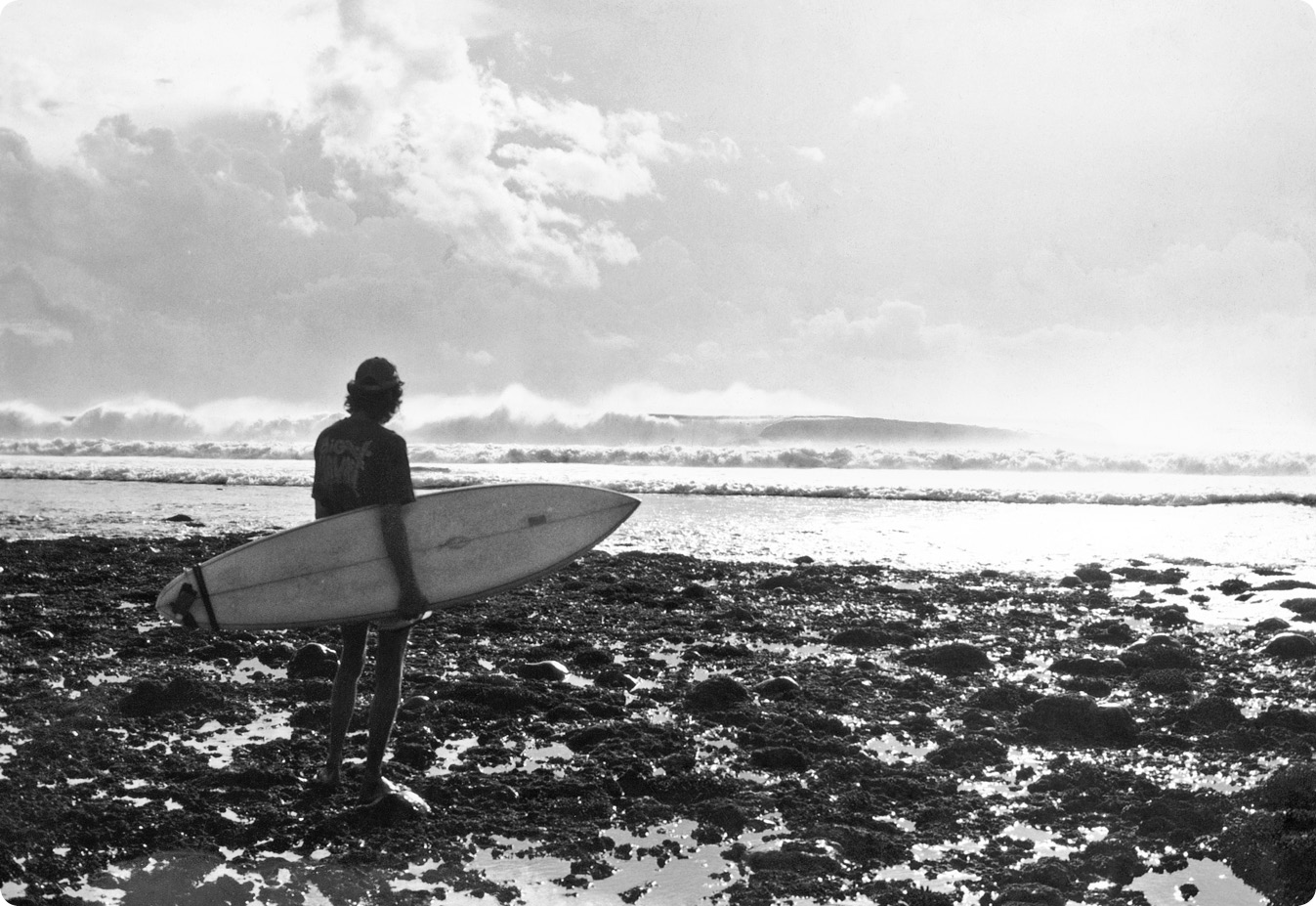

Ignorant of all this, my parents sent me to the nearest junior high, up in working-class Kaimuki, on the back side of Diamond Head crater, where they assumed I was getting on with the business of the eighth grade, but where in fact I was occupied almost entirely by the rigors of bullies, loneliness, fights, and finding my way, after a lifetime of unconscious whiteness in the segregated suburbs of California, in a racialized world. Even my classes felt racially constructed. For academic subjects, at least, students were assigned, on the basis of test scores, to a group that moved together from teacher to teacher. I was put in a high-end group, where nearly all my classmates were Japanese girls. There were no Hawaiians, no Samoans, no Filipinos, and the classes themselves, which were prim and undemanding, bored me in a way that school never had before. Matters werent helped by the fact that, to my classmates, I seemed not to exist socially. And so I passed the class hours slouched in back rows, keeping an eye on the trees outside for signs of wind direction and strength, drawing page after page of surfboards and waves.