TURNED OUT NICE AGAIN

ALSO BY RICHARD MABEY

The Perfumier and the Stinkhorn

Weeds

Food for Free

The Unofficial Countryside

The Common Ground

The Flowering of Britain

Gilbert White

Home Country

Whistling in the Dark:

In Pursuit of the Nightingale

Flora Britannica

Selected Writing 19741999

Nature Cure

Beechcombings

A Brush with Nature

TURNED OUT NICE AGAIN

On Living With the Weather

RICHARD MABEY

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London ECIR OJH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Richard Mabey, 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Fournier by MacGuru Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 052 5

eISBN 978 1 84765 895 1

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

CONTENTS

For Tim, in all weathers

1

TURNED OUT NICE AGAIN

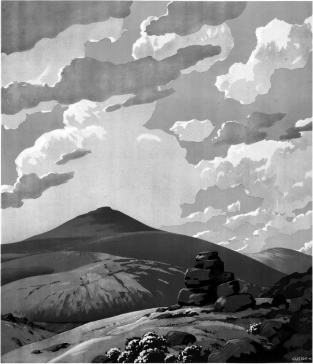

WHEN HURRICANE SANDYS SIEGE of New York last autumn [2012] was smartly followed by waves of marauding floods in Britain, the closing acts in a year of numbing gloom and damp, the idea of global warming began to sound a rather black joke. Ten years ago, some optimists were relishing the prospects of olive groves on the South Downs. Now it looks as if we may be heading full steam for the state of Newfoundland.

But scientists, if wed listened properly, have always insisted that climate change cant be neatly translated into weather patterns. Its likely to generate incoherence, extreme events. Climate may be the big slow-moving backdrop, but weather is what happens here and now, to our settlements and landscapes, to us. In that sense, its part of our popular culture. And that is what I will be exploring in this book, how weather enters and affects our daily lives in Britain, how we talk and write about it, make it the stuff of nostalgia and dreads and, in these uncertain times, how it changes the way we think and feel, about ourselves and the future.

Let me give you an example of what I mean by something that happened to me back in the 1980s as turbulent a time as today, despite our selective memories insisting otherwise. It was an autumn afternoon, and I was meandering through a favourite wood in the Chilterns full of ancient, cranky beech trees. Frithsden has always been an epic weather theatre, a place where freak frosts can scorch the bracken as early as September, and south-westerly gales routinely strew the ground with 300-year-old gothic pollards. It was becoming a kind of woodwreck by then, I suppose, but also gave off the aura of a wood-henge; and whatever melancholy I felt walking among the fallen was always balanced by a frisson of excitement that something wonderfully Promethean was happening inside the green chaos.

Well, on that particular afternoon the weather upped the stakes. Out of a clear blue sky (how we love our weather metaphors!) it began to pour, in sheets. The rain was ferocious, spattering off the golden leaves in silver jets. The whole wood began to change colour, the trunks slicking to slate grey, next years beech-buds glistening like glazed fruit. I huddled under the nearest holly and realised that Id gone to ground right next to the remains of a dear departed. It was the tree I called the Praying Beech, on account of two branch stubs that had fused across it just like a pair of clasped hands. Four years earlier it had been split open by a lightning strike. Bees had nested in the hollow gash. Then it was toppled in a storm. Now this gargantuan supplicant, half as tall as our parish church, was prostrate on the ground. And it was liquefying in front of my eyes. The rain was hammering drills of water at the already rotting trunk, and flakes of bark, fungal ooze, barbecued dregs from the lightning-charred heartwood, began to drip onto the woodland floor like thick arboreal soup.

Peering out from my bush I was mesmerised. I was witnessing the dissolution of a tree, but also what felt like the beginning of something new, the elements of forest life returning to the crucible. The alchemy wrought by that storm changed my whole view of weather and the resilience of nature.

By any standards it was a spectacular weather event. If I hadnt been the only witness, it could have become a star piece of local mythology, part of that ceaseless, nagging narrative we British have about the weather. The poet Samuel Coleridge, one of the greatest writers on what in his day were called Meteors, would have relished the bizarre vision of a dissolving tree. On 26 July, 1802, when a day of topsy-turvy Cumbrian weather had left the sky dotted with flotillas of motionless clouds, looking, he thought, like the surface of the moon seen thro a telescope, hed had a brain-wave. Why didnt he write a set of posters Playbills he called them announcing each day the performance by his supreme Majestys Servants, the Clouds, Waters, Sun, Moon, Stars.

He never got round to it, but I reckon his scheme might go down well today. The playbills would be rather eye-catching, stuck on parish noticeboards alongside the programmes of the local dramatic society. Melting tree on the common! Lightning scar on church door! Five-foot icicles hanging round the council offices keep a careful distance!

Were often mocked for our national obsession with weather, and the fact that some blindingly obvious remark about it is often the first greeting we make to a fellow human. Turned out nice again we say, or The winds got up. Our comments are usually banal catch-phrases, hardly conversation at all, signs perhaps of our stiff maybe frozen-stiff upper-lips. But I find it heartening that we use these coded phrases as a kind of acknowledgement that were all in the weather together. Of course we should be preoccupied. Its the one circumstance of life which we share in common. It affects our bodies, our moods, our behaviour, the structure of our environments. It can change the cost of living and the likelihood of death. It is a kind of common language itself.

And though much of the time we complain about our climatic lot, about our seemingly inexorable legacy of insidious rain and grey skies, theres a little bit of us that relishes rough weather, just so long as it doesnt move into truly malevolent mode. So, we swing between sulky resentment and playful derring-do. The municipal gritters never arrive on time, our plumbing is a disaster, but come the first decent snowfall and we are out playing truant with the toboggans. On the first day of December our local pub in Norfolk throws down the gauntlet by announcing in its own version of the Coleridgean playbill a Guess the Date of the First Snowfall competition, pinned on a board next to the biggest wood-burner in the district. We can make any pastime into a winter sport. I once watched the annual Oxford and Cambridge rugby match played with mad gallantry in four inches of snow and a temperature of minus six C. Glastonbury is now as much a mud festival as a music festival, and has turned the Wellington boot into a fashion item.

Next page