Mabey - The Cabaret of Plants

Here you can read online Mabey - The Cabaret of Plants full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Profile Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Cabaret of Plants: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Cabaret of Plants" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mabey: author's other books

Who wrote The Cabaret of Plants? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Cabaret of Plants — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Cabaret of Plants" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE

CABARET

OF

PLANTS

RICHARD MABEY is one of our greatest nature writers. He is the author of some thirty books, including the bestselling plant bible Flora Britannica, Food for Free, Turned Out Nice Again, Weeds: the Story of Outlaw Plants and Nature Cure which was shortlisted for the Whitbread, Ondaatje and Ackerley Awards. His biography, Gilbert White, won the Whitbread Biography Award. A regular commentator on radio and in the national press, he was elected a Fellow in the Royal Society of Literature in 2012. He lives in Norfolk.

Also by Richard Mabey

The Perfumier and the Stinkhorn

Turned Out Nice Again

Weeds

Food for Free

The Unofficial Countryside

The Common Ground

The Flowering of Britain

Gilbert White

Home Country

Whistling in the Dark: In Pursuit of the Nightingale

Flora Britannica

Selected Writing 19741999

Nature Cure

Fencing Paradise

Beechcombings

A Brush with Nature

Dreams of the Good Life: The Life of Flora Thompson and the Creation of Lark Rise to Candleford

THE

CABARET

OF

PLANTS

BOTANY AND THE IMAGINATION

RICHARD MABEY

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Richard Mabey, 2015

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 401 4

for Vivien

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age

Dylan Thomas

Introduction: The Vegetable Plot

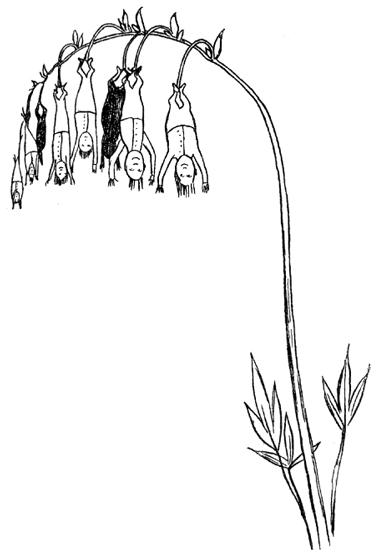

JUST BEFORE HE DIED in 1888 Edward Lear sketched the last of the surreal additions to evolutions menagerie that hed begun with the Bong-tree in The Owl and the Pussycat nearly twenty years before. His Nonsense Botany is a series of impish cartoons of preposterous floral inventions. It includes a strawberry bush bearing puddings instead of fruit, the parrot-flowered Cockatooca superba and the unforgettable Manypeeplia upsidownia, a kind of Solomons seal with minute humans suspended like flowers along the bowed stalk. Lear was a lifelong sufferer from epilepsy and depressive episodes (which he nicknamed the Morbids as if they were a tribe of gloomy rodents) and the obsessive fun he had with words and forms may have been a way of exorcising his melancholy. But I suspect there is more to his final creation. Lear was an astute botanist as well as a brilliant humorist. Hed travelled and painted across the Old World, especially in the Mediterranean, and had seen first hand many of its bizarre plants, including the carrion-stinking dragon arum (which he described as brutal-filthy yet picturesque), and I think his nonsense flora can be seen as a kind of celebratory cabaret, an affectionate satire on the astonishing revelations of nineteenth-century botany.

Manypeeplia upsidownia, from Edward Lears Nonsense Botany.

Thirty years previously Europeans had their first news of the Welwitschia, a Namibian desert plant whose single pair of leaves can live for 2,000 years, grow to immense size but remain in the permanently infantilised state of a seedling. Ten years later Charles Darwin had revealed the barely credible devices orchids used to conscript insect pollinators, including the launching of pollen-laden missiles. In a world of such remarkable organisms why shouldnt there be a fly orchid dangling real flies like Lears Bluebottlia buzztilentia? As for his Sophtsluggia glutinosa, it could well be the filthy dragon arum reimagined as one of the plantanimal cooperatives being unmasked by explorers in the tropics. Lears bionic vegetables were botanys reductio ad absurdum, the last tarantellas of a century in which plants had been just about the most interesting things on the planet. It wasnt a fascination confined to the scientific elite. The general public had been agog, astounded by one botanical revelation after another. In America the discovery of the ancient sequoias of California in the 1850s drew tens of thousands of pilgrims, who saw in these giant veterans proof of their countrys manifest destiny as an unsullied Eden. (There were throngs of rubberneckers and partygoers too: nineteenth-century botany was far from sober-sided.) Similar numbers flocked to Kew Gardens in west London, where one of the star attractions was an Amazonian water lily whose leaves were so brilliantly engineered that their design became the model for the greatest glass building of the nineteenth century. What these moments of excited attention shared was not so much a simple pleasure in floral beauty or the promise of new sources of imperial revenue (though these were there too) but a sense of real wonder that units of non-conscious green tissue could have such strange existences and unquantifiable powers. Plants, defined by their immobility, had evolved extraordinary life-ways by way of compensation: the power to regenerate after most of their body had been eaten; the ability to have sex by proxy; the possession of more than twenty senses whose delicacy far exceeded any of our own. They made you think.

Yet if respect for them as complex and adventurous organisms reached its zenith in the late nineteenth century, it neither began nor ended there. People had been enthralled by and sometimes fearful of the vegetable worlds alternative solutions to living for thousands of years. They contrived myths to explain why trees could outlive civilisations; invented hybrid creatures chimera as models for plants they were unable to understand, and which seemed to intuit symbioses discovered centuries later. Ironically, the same scientific revolution that engaged the public imagination eventually alienated it. Alongside Darwins work, Gregor Mendels discoveries of the mechanisms of genetic inheritance in the late 1860s drove botany deeper in to the laboratory. The workings of plants became too difficult, too intricate for popular understanding. Amateur botanists turned instead to recording the distribution of wild species. The rest of us mostly sublimated our interest in the existence of plants into pleasure at their outward appearance, and the garden has become the principal theatre of vegetal appreciation. Plants in the twenty-first century have been largely reduced to the status of utilitarian and decorative objects. They dont provoke the curiosity shown to, say, dolphins or birds of prey or tigers the charismatic celebrities of television shows and conservation campaigns. We tend not to ask questions about how they behave, cope with lifes challenges, communicate both with each other and, metaphorically, with us. They have come to be seen as the furniture of the planet, necessary, useful, attractive, but just there, passively vegetating. They are certainly not regarded as beings in the sense that animals are.

This book is a challenge to that view. Its a story about plants as authors of their own lives and an argument that ignoring their vitality impoverishes our imaginations and our well-being. It begins with the very first representations of plants in cave art 35,000 years ago, and the revelation that Palaeolithic artists were more intrigued by plants as forms than food. And it ends in a kind of modern cave: the hollow shell of a famous fallen beech, and what this apparently dead relic says about the ability of plants, working as a community, to survive catastrophe. In between, I discuss how medieval clerics and indigenous shamans laid down formal explanations of why one wilding could evolve into a food crop and another into a poison; the debate between Romantic poets and Enlightenment scientists about the kind of vital forces that might lie behind vegetal powers, and whether they echoed the creativity of humans; and today, how the puzzles that so excited the nineteenth century do plants have intentions? inventiveness? individuality? are being explored by a new breed of unconventional and multidisciplinary thinkers.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Cabaret of Plants»

Look at similar books to The Cabaret of Plants. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Cabaret of Plants and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.