The Perfumier and the Stinkhorn

ALSO BY RICHARD MABEY

Weeds

Food for Free

The Unofficial Countryside

The Common Ground

The Flowering of Britain

Gilbert White

Home Country

Whistling in the Dark:

In Pursuit of the Nightingale

Flora Britannica

Selected Writing 19741999

Nature Cure

Fencing Paradise

Beechcombings

A Brush with Nature

THE PERFUMIER AND THE STINKHORN

RICHARD MABEY

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London ECIR OJH

www.profilebooks.com

Shorter versions of these essays were originally broadcast by

Richard Mabey on BBC Radio 3 in autumn 2009, in The Essay series, titled

The Scientist and the Romantic.

Copyright Richard Mabey, 2011

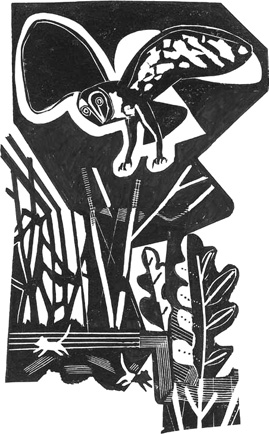

Illustrations by Michael Kirkwood

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 407 4

eISBN 978 1 84765 450 2

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

Contents

THE GREENHOUSE AND THE FIELD

1

The Greenhouse and the Field

WHEN I MOVED from the Chilterns to Norfolk in 2002, I took with me a longing to see a barn owl on my home patch again. Theyd become scarce in Middle England, and I missed their pale vigils over the twilit fields. Id been a year in my new patch before I heard about one. I was tipped off by our window cleaner, who glimpsed it most evenings when dog-walking. It proved to be a late riser, only materialising on the cusp of darkness. When I first saw it, the last light from the west was shining through its almost translucent wing tips. I became rhapsodic about the way it was shuttling night and day together, and scribbled notes about how it seemed to be winnowing the grass, threshing it for food. I was burying the real bird which would have rapidly starved if it had behaved like a threshing machine under bushels of thoughtless visual metaphors. I could have done with some scientific ballast at that moment to ground my flights of fancy.

So when Im occasionally called a Romantic naturalist I wonder whether its an accusation as much as a description: the meticulous observations of the natural scientist corrupted by my overheated imagination; objectivity compromised by my Romantic insistence on making feelings part of the equation.

Well, I suppose it depends what you mean by Romanticism. I rather incline towards Sam Coleridge and John Clares view that nature isnt a machine to be dispassionately dissected, but a community of which we, the observers, are inextricably part. And that our feelings about that community are a perfectly proper subject for reflection, because they shape our relationship with it a more troubled relationship now than it ever was for the eighteenth-century Romantics.

In principle these ideals shouldnt conflict with scientific rigour. Feelings can precede or follow the moment of exact observation without necessarily contaminating its truthfulness. But in practice marrying these two approaches is tricky work, and raises all kinds of puzzles about the terms of our experience of nature. Can you, for instance, closely observe a living organism without in some way taking it out of context, literally or perceptually? Can emotional engagement with nature amount to a kind of subtle take-over? Is it possible for us to sympathetically take another creatures sensory viewpoint without becoming anthropomorphic? Do the technological devices by which we enlarge our understanding of nature enhance or diminish our sense of kindredness with it? Running through these conundrums is the issue of the primacy of our senses, the only channels through which we can relate to the physical world. The natural scientist depends on them for information, but mistrusts their subjectivity and fallibility, and is chiefly interested in how they lead to explanations of nature. The Romantic revels in them for their own sake. They provide sensual experiences as well as sensory data, and are agencies we share with the rest of nature. Wolves and owls and bumblebees stare, sniff and listen too, and the Romantic wants to be part of that great global conversation.

In these six essays I want to reflect on my own rickety attempts to marry a Romantic view of the natural world with a mite of scientific precision. Each essay concentrates on a particular sense sight, taste, smell, hearing, finding your place. In this essay in an oblique way, Im thinking about touch, which is unique among the senses in being both passive and active, about feeling and manipulation.

I began to be fascinated by the natural world in the wasteland that lay at the back of our family house in the Chilterns. This quartermile square of unkempt grass and free-range trees had an exotic history, though I didnt know it at the time. It had been the grounds of a Georgian mansion owned by Graham Greenes uncle Charles, and, before the First World War, the young novelist-to-be was a frequent visitor. He had a secret eyrie on the roof of the Hall, from which hed gaze across the familial parkland and dream of being an explorer.

The estate was broken up in the 1920s, and the old park abandoned. By the time our neighbourhood gang occupied it in the 1950s it was a thrilling wilderness of feral trees, unplumbable wells and shoals of mysterious dells and mounds that were like the tumuli of a lost civilisation. We called it simply The Field, as if there wasnt another one worth bothering about, and used it as our local common. I saw my first barn owl there, hunting over what had once been the Halls tennis courts. I learned how to make dens under the roots of fallen trees, how to walk painlessly over flints, and dreamed, just as Graham Greene had forty years before, of being an explorer. We had a Romantic life out there, playing at noble savages.

But at the edge of The Field I had another kind of den, where the business was more formal. My fathers greenhouse backed onto the wasteland, and when I was about eleven he let me turn one end of it into a makeshift laboratory. As scientific establishments go, it must have been one of the strangest. Id garnered all kinds of household chemicals from Mums kitchen washing soda, borax, vinegar, lime, Epsom salts and put them in jam jars, carefully labelled with their scientific names. They sat in neat rows on the breeze blocks where Dads flower-pots had been. In those days Boots sold chemicals and apparatus over the counter, even to kids, so my pocket money turned into phials of potassium permanganate and sulphur and a gleaming array of flasks, pipettes and funnels. But no dissection knives or collecting bottles. I was mad for chemistry then, but not biology, and it would never have occurred to me to take any living things out of The Field for investigation on the bench. They belonged out in that wild savanna beyond the fence.

Next page