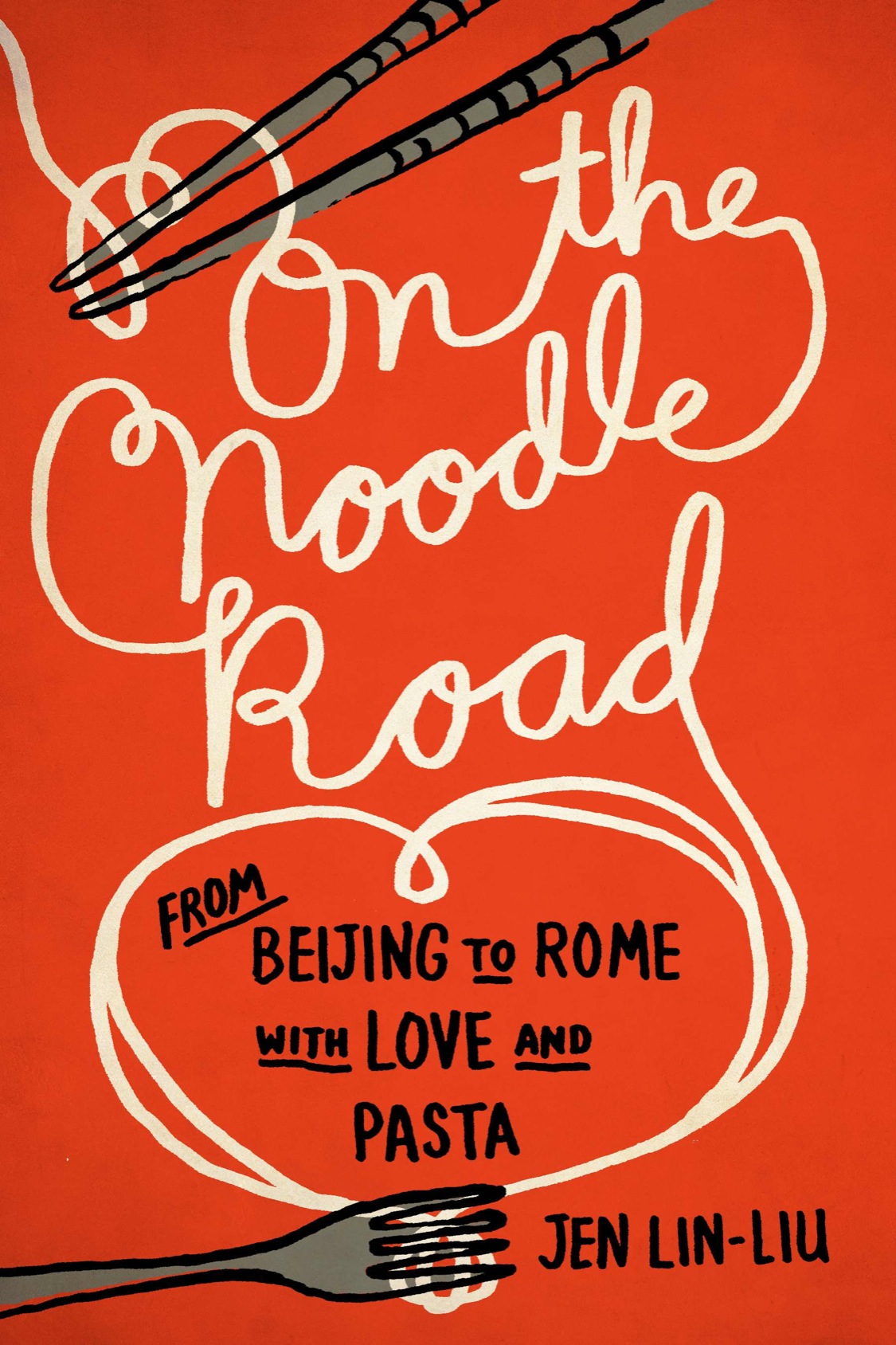

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright 2013 by Jen Lin-Liu

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lin-Liu, Jen.

On the noodle road : from Beijing to Rome, with love and pasta / Jen Lin-Liu.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-101-61619-2

1. Cooking (Pasta) 2. CookingSilk Road. 3. FoodSocial aspectsSilk Road. 4. Food habitsSilk Road. 5. Lin-Liu, JenTravelSilk Road. 6. Silk RoadSocial life and customs. 7. Silk RoadDescription and travel. I. Title.

TX809.M17L58 2013 2013016643

641.82'2dc23

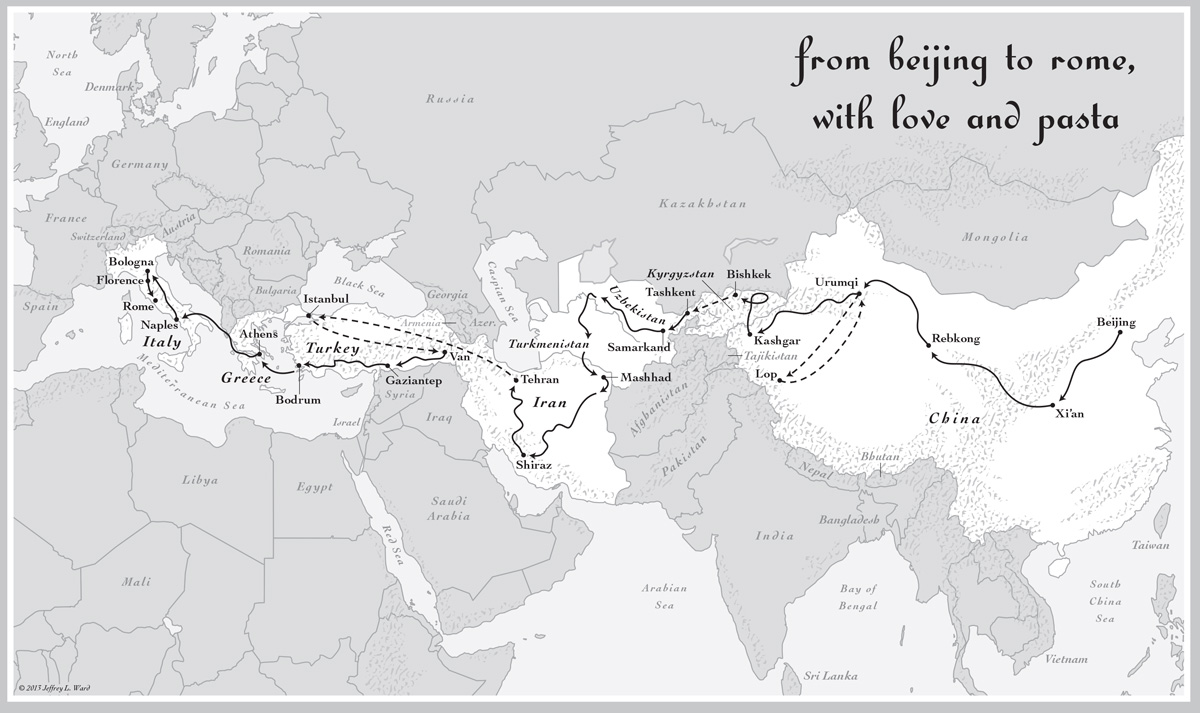

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

prologue

The year after we married, Craig and I went to Italy for Christmas. It was our first time in Europe together, a break from years of living and traveling in Asia. After a week of hiking along precipitous cliffs on the Amalfi coast that dropped into the sparkling blue Mediterranean, we drove to Rome. In a neighborhood called Trastevere, full of winding alleys and couples in embrace, my husband led me to a restaurant called Le Fate and surprised me with a belated holiday gift: a pasta-making class. In the cluttered kitchen, we stood before the chef and proprietor, a man named Andrea. With dark espresso eyes and curly brown hair, the chef happily played the part of the handsome Italian guy female tourists swoon over. He flirted, chatted, and joked with guests as they arrived. But once class began, he cleared his throat and surveyed the room with narrowed eyes. The room fell as silent as a church before mass.

Americans, Andrea declared, think that Italians use a lot of garlic. He placed a single garlic clove on the stainless-steel counter, whacked it with the back of a cast-iron frying pan, and held up the flattened result. We do not use a lot of garlic. Delete this information from your brain!

At the counter, Andrea began breaking eggs with bright yellow yolks into a crater hed made in a mound of finely ground, refined flour. After working the eggs into the flour, he vigorously kneaded and flattened the dough with a rolling pin, gradually stretching the pliable putty into long sheets almost as thin as newsprint. He wound a sheet tightly around the pin, then swung it to and fro, releasing the dough so that it folded over itself in neat S-shaped layers. After cutting them into slivers, he shook the pieces in the air like a magician, unfurling long, wide strands of pasta.

Over my years of learning how to cook in China, Id come across many pasta shapes that echoed ones in Italy. Chinese cats ear noodles resembled Italian orecchiette. Hand-pulled noodles, a specialty of Chinas northwest, were stretched as thin as angel hair. Dumplings and wontons were folded in ways similar to ravioli and tortellini. Even the more obscure shapes of Italian pastahandkerchief-like squares called quadrellini, for examplehad their Chinese counterparts. Each time Id come across a new shape, it seemed coincidental.

But at Andreas that morning, as I watched and mimicked the pasta-making, it all seemed to add up to something more. Andreas movements followed the textbook method for making Chinese hand-rolled noodles, a dish Id practiced countless times in Beijing. It was a revelation. With eggs rather than water, a few extra-clumsy movements, and flour inadvertently winding up all over my hands and face, I, like Andrea, could make fettuccine!

Though the trip was meant to be a break from the Far East, my mind couldnt help drifting back to China as I tasted the food across Italy. In Venice, the seafood risottos reminded me of my grandmothers congee. I learned that the Venetians had a history of sweet-and-sour dishes, thanks to the citys spice trade with the Orient, though many had faded with time. On the Amalfi coast, as we sipped limoncello after dinner, a chef told us that Italians, like Chinese, drank liquor infused with other ingredients in order to relieve everyday ailments.

After that trip, I began to cook more Italian food. In an arrabbiata sauce, I discovered that the balance of acidic tomatoes, hot chilies, and sugar seemed to echo the flavor of spicy noodle dishes in western China. When I drizzled olive oil and vinegar over my salads, I noticed the effect was similar to the sesame oil and black vinegar in the cold salads of Chinas north. In the mushrooms, aged meats, and prodigious Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese grated over pastas, I saw the Italian affinity for a flavor called umami that the Chinese highly prize. As I ate the dishes, I realized that the two cuisines also had common philosophies: they were both essentially humble and rustic, elevating the essence of ingredients over fancy preparations. And both were best home-cooked.

With all the parallels and similarities lingering in my head, I found myself thinking about the familiar story of how Marco Polo brought noodles from China to Italy. Even the Chinese knew the tale, but they liked to tell it with embellishment: Marco Polo also tried meat-filled buns in China, which he attempted to re-create when he returned home. But he couldnt remember how to fold the dough, and Italy ended up with a second-rate mess-of-a-bun called pizza.

Both stories are mythsoverwhelming evidence shows that Italians were eating pasta before the birth of the Venetian explorer. Most experts trace the Marco Polo story back to a 1929 issue of The Macaroni Journal, a now-defunct publication of a pasta trade association. The anonymously written article appeared in between advertisements for industrial pasta-making equipment, and it reads like fiction: Marco Polo arrives by boat to a place that sounds more South Pacific than Chinese and comes across natives drying long strands of pasta. (In reality, Chinese wheat noodles are a tradition of the northern hinterlands and are rarely dried before cooking.) The story was intended to spur the consumption of pasta, back then a novelty to most Americans.