First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PEN & SWORD AVIATION

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley,

South Yorkshire,

S70 2AS

Copyright Alan C. Carey, 2014.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

PAPERBACK ISBN: 978 1 78346 221 6

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47383 631 0

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47383 455 2

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47383 543 6

The right of Alan C. Carey to be identified as the Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

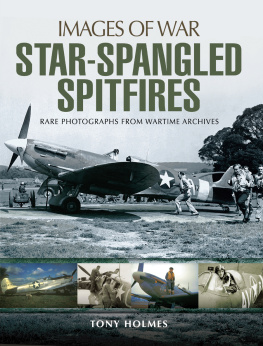

At the beginning of the Second World War American radar technology and night fighter development was considerably inferior to that of the British. By 1943, however, American technology began to surpass British radar systems with the introduction of the SCR-720. Throughout the Second World War aircraft companies in the United States produced 900 night fighters for the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) while the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operated a considerably larger number because existing front-line fighters were better suited for adaptation to the night fighter configuration. Late in November 1945, the USAAF approved military characteristics for a jet-propelled aircraft as a post-war successor to the Northrop P-61. At first the all-weather interceptor was conceived as an aircraft that would be effective in daylight as well as at night or during inclement weather. However, by 1946, Major General Curtis LeMay, Deputy Chief of Staff for Research and Development, indicated that this concept be revised due to the added weight of the radar gear which would limit aircraft performance. Because the heavy radar-equipped all-weather fighter would be no match for a small day fighter, all-weather was to mean primarily night and inclement weather. Military performance characteristics were then revised to conform to this decision and designs for two experimental all-weather aircraft, the Curtiss XP-87 Blackhawk and Northrop XP-89 Scorpion, were selected for investigation.

The Northrop P-61 Black Widow, after production delays, began its operational career in Europe in mid-1944 and later in the Pacific. It remained as the Air Forces only night fighter until 1948. (U.S. Air Force)

Post-war apathy by the American public and government in the wake of the Second World War cut deeply into military appropriations and stifled night/all-weather fighter development, and the newly established U.S. Air Force (USAF) and the Navy continued to rely on piston-driven night fighter aircraft. Changing international situations in Europe and Asia resuscitated interest in night and all-weather interceptors. Soviet aggression with the establishment of communist-bloc countries of Eastern Europe, the Berlin Crisis of 1948, and the Soviets testing of a crude nuclear bomb in 1949, forced the U.S. military on a quest to develop superior strategic bombers and jet interceptors, which in turn, resulted in the development of air intercept radar and all-weather aircraft. Early attempts to develop jet-powered all-weather fighters ran into a series of snags and delays. The Air Force ordered the Curtiss XP-87 in December 1945, but it ran into developmental difficulties and the Air Force abandoned the project, which incidentally ended Curtiss thirty-year history as an aircraft manufacturer. The P-89 Scorpion seemed to hold greater promise, but it too ran into teething troubles and its acceptance and delivery did not occur until 1952.

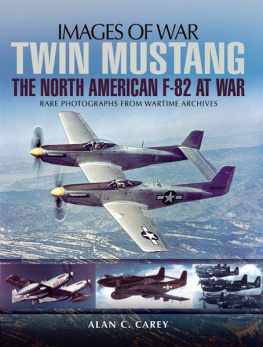

Development of jet-powered all-weather aircraft would be slow and, until such time when this type became available, the U.S. Air Force needed an interim aircraft. In the immediate post-war period, the P-61 had formed the bulk of the night fighter force. Due to the lack of any suitable jet-powered replacement, the P-61 soldiered on for a few more years. However, manoeuvres held in the North-western United States early in 1948 quickly confirmed the Black Widows limitations and the Air Force deemed the aircraft as having no tactical value in defensive operations. In order to help fill the gap until the F-89 Scorpion became operational, North American Aviation (NAA) developed a night and all-weather adaptation of the piston-engine North American F-82 Twin Mustang.

The U.S. Air Force, in need of a jet-powered all-weather fighter to replace its Second World War P-61 Black Widow, narrowed its search down to the Curtiss XP-87 pictured here and the Northrop XP-89 Scorpion. Ultimately, the underpowered XP-87 lost to the XP-89. (U.S. Air Force)

Since the P-82, like the P-61, would be of little value in daylight operations, the Air Force assigned such jet interceptors as the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star (later F-80) and Republic P-84 Thunderjet (F-84) to fighter-interceptor squadrons, which began replacing the single-engined, propeller-driven North American P-51 (F-51) Mustang in the Air Force inventory. These jet aircraft possessed the required speeds to combat enemy bombers of the Boeing B-50 type but both fighters lacked the electronic equipment to allow them to operate at any other time than during daylight (again, the weight of 1950s-era airborne radar technology precluded its use in a small high-speed interceptor). In turn, beginning late in 1949, the North American F-86A Sabre replaced the F-80 and F-84. By the end of 1950, of the 365 aircraft assigned to the U.S. Air Defense Command (ADC), 236 were F-86A and E models. Therefore, without a real all-weather interceptor, the Air Force had no other alternative but to place its reliance on a dual fighter force, with jet aircraft for daytime operations and radar-equipped F-82s for night and inclement weather interceptor missions.

The Northrop XP-89 Scorpion seemed the answer but continued power plant problems delayed production of the Scorpion forcing the Air Force to rely on modifications of North American Aviations F-82 Twin Mustang. (U.S. Air Force)

Chapter One:

Development

Possibly one of the oddest American aircraft to go into full production after the end of the Second World War, the P- (later) F-82 Twin Mustang series was the last mass production propeller-driven fighter acquired by the U.S. Air Force. Originally designed as a long-range bomber escort during the Second World War, it evolved into a night and all-weather fighter during the post-war years. The original concept of the XP-82 traces back to the development of North American Aviations XP-51 Mustang in 1940 and the production of subsequent variants of that aircraft as a long-range fighter to protect Allied bombers against the German Luftwaffe and, subsequently, to provide cover for Boeing B-29 bombers in the Pacific. However, the Air Force lacked an interceptor with an extreme-range capability. The USAAF fighters with the longest range during that conflict were the P-51D Mustang, with a maximum range of 1,600 miles, and the Lockheed P-38J Lightning with a maximum range of 2,200 miles. Both aircraft were capable of escorting B-17 and B-24 bombers from bases in England to the heart of Germany; but it was another story in the Pacific.

Next page