Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

John Edwards

MARY I

The Daughter of Time

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2016

Copyright John Edwards, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design by Pentagram

Jacket art by Montse Bernal

ISBN: 978-0-241-18411-0

Introduction

Mary I of England, the first sovereign queen of modern England, Wales and Ireland, is generally not even accorded this title. Instead she is normally referred to just as Mary Tudor. The long reigns of her father Henry VIII (150947) and her much younger half-sister Elizabeth I (15581603) have effectively submerged Mary, as well as her much younger half-brother Edward VI (154753). Edward and Marys reigns are, all too easily and frequently, glossed over or dismissed as unfortunate blips in Englands supposedly predestined progress to Protestantism, insular uniqueness and world empire. Bloody Mary is depicted as the very opposite of the Virgin Queen who succeeded her. While Elizabeth is Gloriana, a woman everyone thinks they know and admire, Mary is seen as a grim-faced Catholic fanatic who wore black, was wrinkled and ugly and lived in the gloomy shadows of childlessness and political and religious failure.

Until quite recently, even the most learned historians of Marys reign have generally, in their ill-disguised male contempt for her as a woman who presumed to govern (and wasnt Elizabeth!), faithfully repeated the criticisms made of her by some nineteenth-century female writers. In particular, Maria Callcott, in her Little Arthurs History of England, wrote:

Mary, the daughter of Henry VIII and of Catherine of Aragon, was so cruel that she is always called Bloody Mary.

The mighty novelist Charles Dickens got in on the act too, writing:

As BLOODY QUEEN MARY, this woman has become famous, and as BLOODY QUEEN MARY she will ever be justly remembered with horror and detestation in Great Britain By their fruits ye shall know them, said OUR SAVIOUR [Matthew 7:20]. The stake and the fire were the fruits of this reign, and you shall judge this Queen by nothing else.

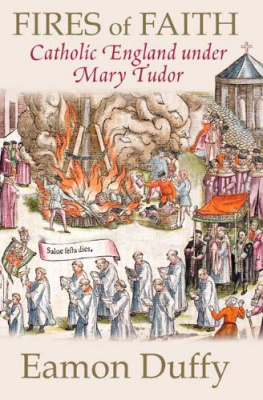

Dickens is referring to the death by burning, in Marys short reign (15538), at the hands of the secular authorities on behalf of the Catholic Church, of approximately 300 men and women on charges of heresy. This issue must, of course, be confronted, but not necessarily in such a manner.

In human as well as historical terms, there is also a stark contrast between Mary and her half-brother Edward. The boy king, cut down by disease, never reached adulthood, whereas Mary did. Thus she, unlike her male sibling, may be judged as a responsible ruler, if only for a short time, in comparison with the much longer reigns of her father and sister. It could be said that Mary had the worst of both worlds full responsibility for what happened, but only a short time in which to achieve anything. Yet Mary, not Elizabeth, was the pioneer of English female sovereignty, in a society which generally regarded womens authority over men as intrinsically unnatural, and even wicked. This was a problem that Henry and Edward by nature never faced, and one which Elizabeth too had to fight very hard to overcome. In many ways, Mary was the pioneer not only of female monarchy in England, but also of her countrys future role as a world power. It is, of course, totally impossible to study her life without knowledge of what happened afterwards, from the first Queen Elizabeth to the second, but this short Life is written with such an approach in mind. There can be no English ruler who more needs the later historical and ideological detritus to be cleared away, if she is to be understood with any kind of authenticity.

In 1524, when Mary was just eight years old, Juan Luis Vives, a distinguished Spanish Humanist who had been put in charge of her education, presented for her use a collection of Classical proverbs and sayings modelled on the famous Adages of Erasmus of Rotterdam. It was entitled Satellitum sive symbola (Companion or guidelines), and it contained the phrase Veritas filia temporis, which Mary chose as her personal motto. Its literal meaning is Truth is the daughter of Time, but in her case it might be better rendered as The truth will out.