www.headofzeus.com

To Simon and Katie Roberts

Contents

Main Text

: The High Priest of Respectability

Endmatter

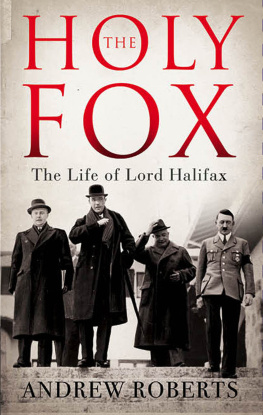

All writers tend to keep a special place in their hearts for their first book, whatever it is, and I certainly feel that way about The Holy Fox: The Life of Lord Halifax , which I wrote between 1988 and 1991 after leaving my job in merchant banking owing to my functional innumeracy. As I cast my eyes down the list of the one hundred or so people who knew Lord Halifax whom I interviewed for the book, I see that almost every single one of them is now dead, and the youngest of those who are still alive is in his ninetieth year. It could therefore not be written today.

In the more than two decades since the publication of The Holy Fox there has been an avalanche of books written on the Chamberlain Government, the Appeasement policy, the politics of the year 1940, the life of Sir Winston Churchill, the Second World War, and the many other aspects of history which Lord Halifaxs life and career touched in some way. Yet there has only been one piece of brand new information that has come out about the crucial meeting of 9 May 1940 in which it was decided that on his resignation Neville Chamberlain would recommend Winston Churchill to King George VI as his successor, rather than Chamberlains (and indeed the kings) first choice of Lord Halifax. That is to be found on page 476 of Amanda Smiths 2001 edition of Hostage to Fortune , her edition of the private papers of her grandfather Joseph P. Kennedy, the American Ambassador to London from 1938 to 1940.

Knowing he was dying of cancer indeed he had less than three weeks to live Chamberlain invited Kennedy to his home in the country on 19 October 1940 to say farewell. According to Kennedys diary, they discussed the May meeting, and Chamberlain told Kennedy that after the Labour Party leaders had indicated that they would not serve in a National Government under him, He then wanted to make Halifax P[rime] M[inister] and said that he would serve under him. Edward, as [is] his way, started saying Perhaps I cant handle it being in the H[ouse] of Lords and Finally Winston said I dont think you could. And he wouldnt come and that settled it.

Under this formulation the only time that Chamberlain bore witness about what happened only five months earlier there is no elongated silence as in Churchills account written six years later, unless that can be surmised from the capital letter in the word Finally (and of course the word itself). Equally Churchills account, in which the premiership effectively fell to him without his doing anything to demand it, is somewhat contradicted by Chamberlains account of Churchill saying to Halifax that he didnt think Halifax could handle the premiership from the House of Lords. I wish Amanda Smiths book had been published ten years earlier as Id have incorporated it into my narrative, but now readers will have this extra piece of evidence in their piecing together of what happened that fateful afternoon.

It is gratifying for me that the central argument of The Holy Fox , namely that Halifax was instrumental in turning the British Government against appeasement in the face of the prime ministers opposition in the post-Munich period, has gained the endorsement of a number of respected academic historians of the period. In the words of Professor David Dutton (writing in his chapter Guilty Men? Three British Foreign Secretaries of the 1930s, in The Origins of the Second World War: An International Perspective (2011), edited by Professor Frank McDonough): far from being some sort of Chamberlain puppet, Lord Halifax played a decisive role in frustrating Chamberlains preferences and pushing British policy down the road to war. That older Conservative tradition identified by recent scholarship found its contemporary exponent in Halifax, who, in his own quiet way, became as essential to his Prime Minister as Palmerston had been a century earlier.

I am delighted that Head of Zeus are republishing The Holy Fox, and that as the seventy-fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War approaches its account of the critical role played by Halifax in Britains approach to that conflict will once again be made available to a wide readership.

A NDREW R OBERTS

Cornell University

September 2013

Only a matter of hours before Hitler unleashed his Blitzkrieg on the West, four men met in the Cabinet Room at No. 10, Downing Street, to decide who should be Britains war leader. Virulent and mounting personal opposition in the House of Commons had forced Neville Chamberlain to realize that he could not continue as Prime Minister. He and David Margesson, the Government Chief Whip, therefore convened a meeting for 4.30 p.m. on Thursday, 9 May 1940, to decide upon a successor.

The two contenders, Edward, Lord Halifax and Winston Churchill, could not have been more different. Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, was a calm, rational man of immense personal prestige and gravitas , his career an uninterrupted tale of achievement and promotion. He had also for some time seemed to be Chamberlains heir apparent. Across the Cabinet table sat Churchill, the romantic and excitable adventurer, whose life was a Boys Own story of cavalry charges, prison escapes and the thirst for action.

Often portrayed as a set-piece contest between curriculum vitae and genius, this was actually nothing of the sort. For all his oratorical abilities, Churchill was universally regarded as lacking that essential quality for a Prime Minister: Judgement. Baldwin had put it best when he said:

When Winston was born lots of fairies swooped down on his cradle with gifts imagination, eloquence, industry, ability and then came a fairy who said, No one person has a right to so many gifts, and picked him up and gave him such a shake and a twist that with all these gifts he was denied judgement and wisdom. And that is why while we delight to listen to him in the House we do not take his advice.

The ill-fated action Churchill had taken over Gallipoli, the Sidney Street siege, the Russian Civil War, the Gold Standard, Indian policy, the Abdication, Palestine and a host of other issues had led to deep distrust of his political acumen. The Tories could not forgive his decade-long attack on the government from their own back-benches nor forget that he had twice crossed the floor of the House. Labour regarded his zeal at Tonypandy, at the General Strike and over India as the mark of the blackest reactionary.

Finally, it had been Churchill who, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had been most closely responsible for the greatest dbcle of the war so far, the very setback which had precipitated the present crisis: the defeat of the expeditionary force to Norway.

Halifax, however, was regarded by many as a perfect foil for Churchills impetuosity. His Viceroyalty of India had been seen as a triumph of patience and reform. His efforts to stiffen resistance after Munich made him the acceptable face of Chamberlainism. His ceaseless campaign to bring all parties into the Government was appreciated by the Opposition leaders, with whom he kept on good personal terms. His calm resolution, Olympian manner and, above all, his respectability and reputation for sound judgement led many to think of him as the ideal national leader, who could oversee Churchills day-to-day running of the war.

Both Chamberlain and King George VI wanted Halifax. The Government wanted Halifax. The great majority of Conservative MPs wanted Halifax. The Times , the City, the House of Lords and Whitehall all wanted Halifax. Opposition leaders had indicated that they would prefer him and even Churchill himself told friends that he too would serve under him.

Next page