THE ZAD

AND NOTAV

Territorial Struggles and the

Making of a New Political Intelligence

Mauvaise Troupe Collective

Translated and edited

with a Preface by Kristin Ross

This English-language edition published by Verso 2018

Originally published in French as Contres: Histoires croises de la zad

de Notre-Dame-des-Landes et de la lutte No TAV dans le Val Susa

Editions de leclat 2016

Translation and Preface Kristin Ross 2018

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-496-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-497-9 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-498-6 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ross, Kristin, translator, editor. | Collectif Mauvaise troupe.

Title: The Zad and NoTAV : territorial struggles and the making of a new political intelligence / Mauvaise Troupe collective ; translated, edited and introduced by Kristin Ross.

Other titles: Contrees. English

Description: English language edition. | London ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso, the imprint of New Left Books, 2017 | Includes bibliographical references. | Translation of: Contrees : histoires croisees de la zad de Notre-Dame-des-Landes et de la lutte No TAV dans le Val Susa.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022087 | ISBN 9781786634962 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781786634986

(US E-book) | ISBN 9781786634979 (UK E-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Government, Resistance

toFranceNotre-Dame-des-LandesHistory21st century. | Government, Resistance toItalySusa ValleyHistory21st century. | Protest

movementsFranceNotre-Dame-des-LandesHistory--21st century. | Protest

movementsItalySusa ValleyHistory21st century. | Regional

planningEnvironmental aspectsFranceNotre-Dame-des-Landes. | Regional

planningEnvironmental aspectsItalySusa Valley.

Classification: LCC HN425.5 .C65413 2017 | DDC 323/.044094dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022087

Typeset in Minion Pro by Hewer Text UK, Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

Preface: Making a Territory

Kristin Ross

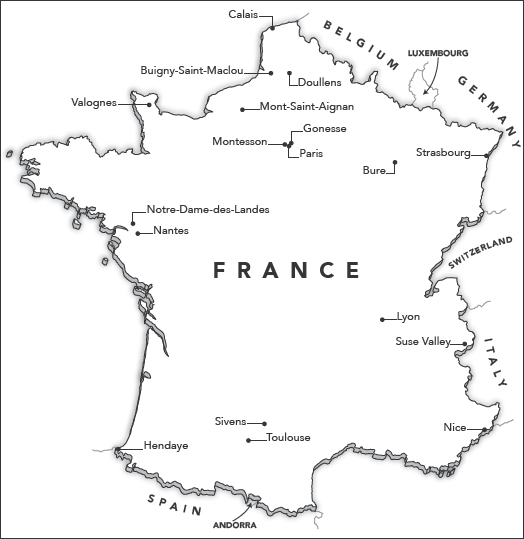

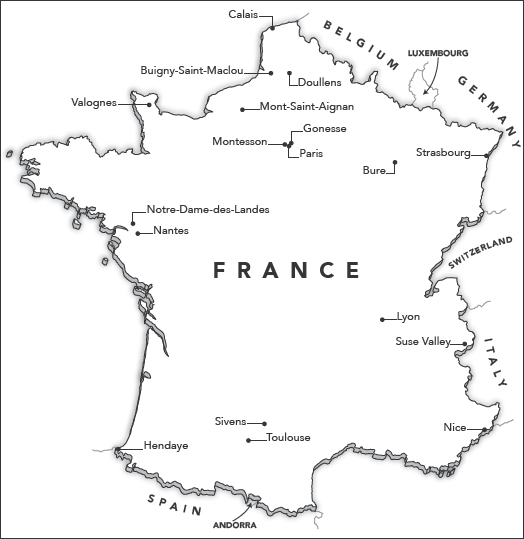

In recent years the rise in the number of occupations and attempts to block what have come to be known as large, imposed, and useless infrastructural projects bears witness to a new political sensibility. It is as if some time toward the end of the last century, people throughout the world began to realize that the tension between the logic of development and that of the ecological bases of life had become the primary contradiction ruling their lives. And, in many rural and semirural regions throughout the world in the Larzac in France, for example, or at Sanrizuka (Narita) in Japan struggles sprang up against state control of land management. These were movements whose particularity lay in being firmly anchored in a particular region or territory. From the 1988 opposition to a large-scale dam on the Xingu River in Altamira, Brazil, through the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, to the Standing Rock Siouxs recent resistance to the North Dakota Pipeline, situated movements of this kind in the Americas have tended to be characterized by an indigenous base and leadership.extension of a nightmarish world, they unite with their American counterparts in reconfiguring the lines of conflict of an era. In so doing, they make visible the silhouette of a new political grasp on the everyday and a way of managing common affairs. Henceforth, it seems, any effort to change social inequality will have to be conjugated with another imperative that of conserving the living. Defending the conditions for life on the planet has become the new and incontrovertible horizon of meaning of all political struggle.

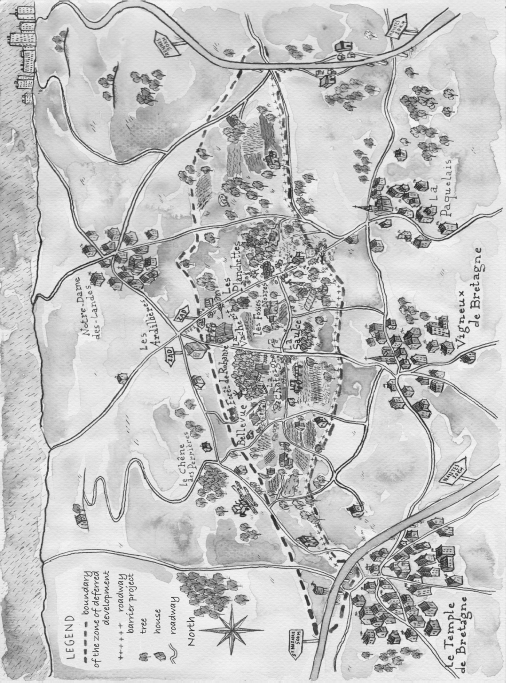

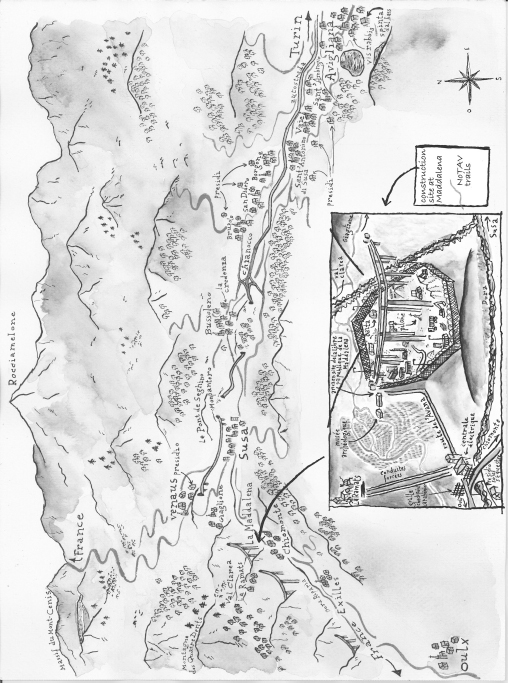

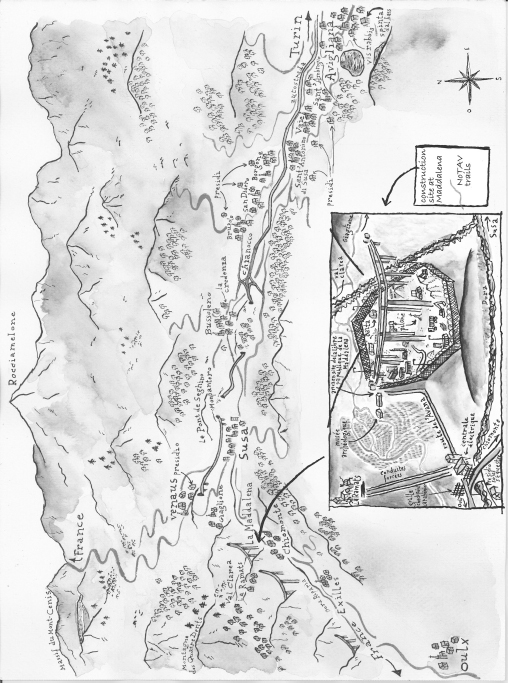

The occupation of a small corner of the countryside outside of the village of Notre-Dame-des-Landes in western France is the site of the longest-lasting battle in the country today. For forty years the construction of an international airport on that spot has threatened to destroy 4,000 acres of agricultural land, wetlands, and woods. In the Susa Valley in the Italian Alps, the quasi-totality of a valley inhabited by 70,000 people has battled for over a quarter of a century the construction of a high-speed train line (Treno ad Alta Velocit or TAV) through the Alps between Turin and Lyon. While it is frequently said of indigenous peoples that they stand in the way of progress, in each of these regions in Europe a heterogeneous but highly efficient coalition of people has effectively done just that. They have succeeded in delaying, obstructing, and perhaps, ultimately time will tell blocking the progress of construction and the destruction of their regions.

In the first chapter of this book readers will find the most thorough chronology of the two movements available in English here, though, is a brief sketch of the two projects that generated the opposition.

The Airport and the Train

Justifications for, and sponsors of, a new airport on the outskirts of the city of Nantes in western France have changed over the years since their origins in the dreams and magical thinking of a regional bourgeoisie entranced by the booming developmental rhetoric of the peak years of the Trente Glorieuses. At one point, the airport was slated to be the departure and landing point for the Concorde, in an attempt to relieve Paris of the massive noise pollution this ill-fated technological The sum spent on studies designed to give a scientific veneer to the project far exceeded the purchase price of the land needed for its realization an area regularly described as almost a desert. This description could only have been the echo of the familiar colonial trope indicating a perceived scarcity of population preceding invasion, since the area chosen was in fact largely wetlands an environmental category virtually unrecognized in the 1970s.

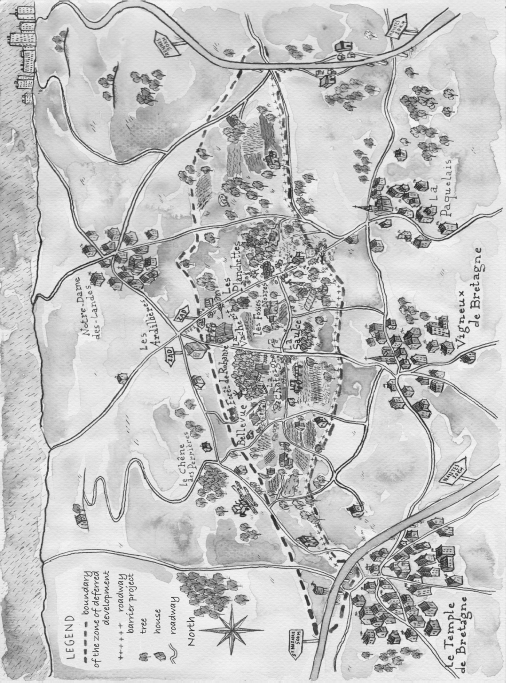

And so, an area of some 4,000 acres containing several dozen farms was designated in 1974 as the site for the future airport. The area was decreed by the state to be a ZAD, or zone damnagement diffr, a zone of deferred development. This administrative status allowed the state time to begin buying up land from farmers willing to sell out or, in the familiar pattern of rural exodus, to buy whenever a farmer died and his children sold out. Yet while the slow process of expropriation was continuing, the energy crisis sunk the overall project into one of the intermittent long naps that mark its history. This one lasted throughout the 1980s and 1990s the airport was forgotten, not entirely dead but not entirely alive either. In the meantime, though, the zone profited from what could only be called a secondary gain from the illness of having been destined to be one day covered over in concrete: much like Cuba during the Special Period, it had inadvertently been transformed, de facto, into a protected agricultural zone. Developers were hesitant to build near a future airport and no one wanted to live next door the suburbanization that was befalling much of the area around Nantes was held at bay in Notre-Dame-des-Landes.