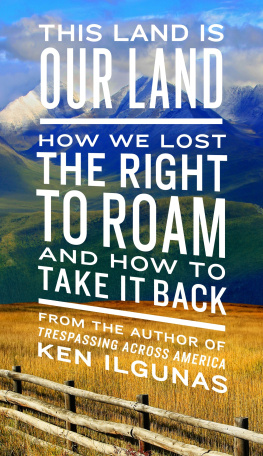

K EN I LGUNAS is an author, journalist, and backcountry ranger in Alaska. He has hitchhiked ten thousand miles across North America, paddled one thousand miles across Ontario in a birchbark canoe, and walked 1,700 miles across the Great Plains, following the proposed route of the Keystone XL pipeline. Ilgunas has a BA from SUNY Buffalo in history and English, and an MA in liberal studies from Duke University. The author of travel memoirs Walden on Wheels and Trespassing Across America, he is from Wheatfield, New York.

A LSO BY K EN I LGUNAS

Walden on Wheels

Trespassing Across America

PLUME

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Ken Ilgunas

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND

Words and Music by Woody Guthrie

WGP/TRO- Copyright 1956, 1958, 1970, 1972, and 1995 (copyrights renewed) Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, NY, administered by Ludlow Music, Inc.

Used by Permission.

Plume is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

has been applied for.

ISBN 9780735217843 (paperback)

ISBN 9780735217850 (ebook)

Version_1

For my best friends, Josh and David

Was a high wall there that tried to stop me

A sign was painted said: Private Property,

But on the back side it didnt say nothing

This land was made for you and me.

Original verse from This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie

Contents

Introduction

It is not in the nature of human beings to be cattle in glorified feedlots. Every person deserves the option to travel easily in and out of the complex and primal world that gave us birth. We need freedom to roam across land owned by no one but protected by all, whose unchanging horizon is the same that bounded the world of our millennial ancestors.

E. O. Wilson, The Creation

In his poem Mending Wall, New England poet Robert Frost and his neighbor repair a stone wall that separates their properties. Its their annual tradition. Each spring, they rough up their hands lifting and setting the fallen stones, playfully casting spells on the wobbling wall to Stay where you are until our backs are turned!

Theres irony in repairing an unneighborly wall because the two neighbors are indeed neighborly as they work across from one another. To Frost, the wall makes no sense because it only divides him from his good neighbor, as well as Frosts harmless apple trees from his neighbors harmless pines. Something there is that doesnt love a wall, Frost muses. The neighbor, as well, isnt quite sure why they have the wall. When Frost asks him why they rebuild it every year, the neighbor can only recite the saying of his father: Good fences make good neighbours. Even Frost, with his doubts and musings, feels strangely compelled to take part ineven initiatethe yearly tradition.

The way I read it, Frosts poem isnt just about walls, divisions, or neighbors. At its core, the poem grapples with the trouble of unquestioned tradition and the gravitational pull of precedent. Mending Wall urges us to rethink our traditions, specifically our tradition of closing off lands to our fellow countrymen and women. So lets think about the poem, not from the perspective of two neighbors in the year 1914 in New England, but from the perspective of 324 million people in twenty-first-century America, a country arguably more divided now than its been since the Civil War. Lets think about our own unquestioned devotion to fences, to No Trespassing signs, and to an unbending understanding of private property. Lets think about why we, as a matter of course, forbid our fellow citizens from our lands.

This book calls for the right to roam across America. It calls for opening up private land for public hiking, camping, and other harmless forms of recreation. Skeptics, and more than a few landowners, may reasonably argue that bringing into question something as sacrosanct and entrenched in American culture as private property would be, in our present world, a rather ridiculous notion. Considering how there are no ongoing movements calling for the right to roam, no proposed bills, and no politicians lobbying to open up private land, one might argue that what Im proposing is fantastical, unreasonable, and just plain foolhardy, especially when our country is plagued by problems more serious than our nature deficit disorders and recreational access issues. One could charge that Im tilting at windmills, that Im advocating for something unattainable, that Im calling for changing an institution that many Americans in fact cherish.

To these charges, Id have to answer, Maybe so. But I would also argue that our problems with physical and mental health, of dwindling green spaces, of environmental injustice, and of inequality in land ownership are all serious and will only get worse in the decades to come. If things keep going the way they are, then by the end of the twenty-first century few of us will have access to our last havens of natural space and to the vanishing pleasures of solitude, peace, adventure, and the hundred other benefits that spring from a relationship with the natural world. Thats hardly a bold prediction, because today, early in the first half of the twenty-first century, few of us have easy access to these places and the feelings they stir.

Should you be turned off by what may be a radical, or even heretical, idea, lets remind ourselves that there is no harm in thinking for the future, even the deep future. If it makes it easier to read, then consider this book a book for the twenty-second centurya book that calls for something unlikely right now but plants a seed that may one day grow branches under which future generations may walk. (Beware: Many more hiking metaphors to come.) At the very least, I hope this book encourages us to think about an institution that is so ever present that we seldom give it a thought and that we accept without scruple. I speak of property, specifically our American brand of absolute and exclusionary private property.

Now that Ive performed the delicate footwork of (hopefully) assuring the reader that this book has not in fact been written with a thoughtless zeal, a reckless radicalness (or a certifiable insanity), I hope youll join me as I take a bold step forward, through the gaps in our fallen walls and unmended fences, into the great American countryside, where I believe wed be a better nation if we did away with the faulty notion that good fences make good neighbours. I believe the opposite to be true.