Contents

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois

To the memory of my brother, Christopher Anthony Stead, a workingman and artist

2014 Arnold Stead

Haymarket Books

PO Box 180165

Chicago, IL60618

773-583-7884

info@haymarketbooks.org

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-226-1

Trade distribution:

In the US, through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Publishers Group Worldwide, www.pgw.com

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please contact Haymarket Books for more information at 773-583-7884 or info@haymarketbooks.org.

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and the Wallace Action Fund.

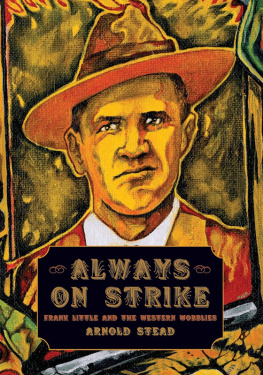

Cover design by Julie Fain. Cover image from a painting by Keith Seidel.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Contents

Introduction 1

Chapter One: The Western Wobblies 15

Chapter Two: The Free-Speech Fights 41

Chapter Three: Iron Miners, Harvest Hands,

and Oil Workers 69

Chapter Four: Urgency and Conspiracy 111

Chapter Five: Big Bill Haywood and Frank Little 143

Chapter Six: Three Western Wobbly Martyrs 155

Conclusion: Frank Little, Where Are You

Now that We Need You? 163

Acknowledgments 167

Sources 169

Notes 175

Index 183

Introduction

Many years after the fact, during a far more conservative period of his life, Ralph Chaplin writes that Frank Little was the first to arrive for a meeting of the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World in late July of 1917. Although we may have reason to doubt his memory (it has Little leaving Chicago en route to Butte a full week after that citys press announced the hobo agitators arrival in Montana), Chaplins vivid description of his last encounter with Little has a ring of truth to it. He writes: Frank wore his Stetson at the same jaunty angle, and his twisted grin was as aggressive as ever. The meetings primary purpose was to decide whether or not Wobblies should register for the draft. Board member Richard Brazier, like Chaplin and Haywood, thought opposing conscription would put the International Workers of the World, known as the IWW or the Wobblies, out of business. Little shot back at him: Theyll run us out of business anyhow. Better to go out in a blaze of glory than to give in. Either were for this capitalist slaughter fest or were against it. Id rather take a firing squad.

In response, Bill [Haywood] looked angry, the others bewildered, and Chaplin hastily wrote a compromise statement. The board would not sign it, but instead told Chaplin to send it under his signature. He remembers taking the statement with him when he registered for the draft. The following day, July 25, Chaplin writes that Little hobbled up to my offices to say goodbye. The latter said, Youre wrong about registering for the draft. It would be better to go down slugging. Chaplin marveled at Littles courage in taking on a difficult and dangerous assignment like [the Butte strike] in his present condition. Chaplin continues:

Its a fine specimen the I.W.W. is sending into that tough town, I chided him. One leg, one eye, two crutchesand no brains!

Frank laughed, he lifted a crutch as though to crown me. Dont worry, fellow worker, all were going to need from now on is guts.

That was the last time I saw Frank Little alive.

Historian Arnon Gutfeld describes the assassination of Frank Little: At about three a.m. the morning of August 1, a large black car stopped in front of 316 North Wyoming Street. Six masked men emerged from the vehicle and entered a boarding house next to Finnlander Hall where Frank Little was staying. The men frightened the landlady, Mrs. Nora Byrne, by kicking in the door of a room they mistakenly thought Little to be occupying. She asked them what they wanted and they replied, We are officers and we want Frank Little. His abductors did not allow the hobo agitator to dress, and when he resisted they carried him to the black automobile.

The car sped away, but stopped after traveling a short distance and Little, still in his underwear, was tied to the car bumper. He must have been dragged a considerable distance, for his kneecaps were later found to have been scrapped off. He was taken to the Milwaukee Bridge, a short distance outside the city limits. There he was severely beaten, as bruises on his skull indicated, and hanged from a railroad trestle. Pinned to his underwear was a six-by-ten inch placard with the inscription, Others take notice, first and last warning, 37-77. On the bottom of the note, the letters L-D-C-S-S-W-T were printed, and the letter L encircled.

The numbers 37-77 aroused a good many theories, including one by a Butte citizen who believed it was Littles draft number and that he committed suicide to avoid being inducted into the military. It is now generally believed, however, that the figures designate Montana specifications for a grave: three feet wide, seven feet deep, and seventy-seven inches long. The Butte press seemed to think D-C-S-S-W-T stood for the last names of men the vigilantes were going to visit next: William Dunne, Tom Campbell, Joe Shannon, Dan Shovlin, John Williams, and Leon Tomich; all of whom were leaders of the Metal Mine Workers Union.

I first discovered Frank Little quite by accident. With no students to occupy me during office hours, I began to browse through the Encyclopedia of the American Left and found in an entry on the great novelist Dashiell Hammett that some people believed he had been involved in the lynching of Frank Little. Long a Hammett fan, I had never heard of Frank Little. Under the formers name I found a fragment of a thought-provoking figure, and I have been collecting Frank Little fragments ever since. If not for my interest in Dashiell Hammett, creator of characters such as Sam Spade and Nick and Nora Charles, I might well have never discovered Frank Little, a legendary figure in his own right. Hammett would have been about twenty-one years old when Little was murdered and highly unlikely to have had any notions of one day being a respected writer of hard-boiled detective fiction.

Young Hammett was working as a Pinkerton operative in Butte, Montana, the summer Frank Little was murdered. He was in town to help break the miners strike that Little was probably leading, clandestinely of course. In those days, the agency that Alan Pinkerton had founded at the behest of the nations biggest bosses, particularly the railroad magnates, did its bread-and-butter business as a strike-breaking force. The Industrial Workers of the World was involved in a strike against the Butte branch of the Anaconda Copper Company so the company hired Pinkertons. According to William F. Nolan, one of Hammetts biographers, Hammett discovered that one man in particular was causing major trouble for the mining company. His name was Frank Little, a labor union organizer known as the hobo agitator. Little, who had lost one eye, was part Indian and possessed a warriors tenacity and courage; he would not be bluffed or scared off. Union members supported him enthusiastically as he raved and shouted against injustices in the mines. Might we assume the man who could not be bluffed or scared off had to be killed?

In the early 1930s, Hammett told Lillian Hellman that an officer of Anaconda Copper had offered him five thousand dollars to kill Frank Little. He also said: I had no political conscience in 17. I was just doing a job, and if our clients were rotten it didnt concern me. They hired us to break up a union strike, so we went out there [Butte] to do that. Hammett said he turned down the offer, but Hellman seems convinced the incident played a pivotal role in his life. In Scoundrel Time she tells her readers: Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder... I think I can date Hammetts belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Littles murder.

Next page