Contents

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois

To the memory of my brother, Christopher Anthony Stead, a workingman and artist

2014 Arnold Stead

Haymarket Books

PO Box 180165

Chicago, IL60618

773-583-7884

info@haymarketbooks.org

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-226-1

Trade distribution:

In the US, through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Publishers Group Worldwide, www.pgw.com

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please contact Haymarket Books for more information at 773-583-7884 or info@haymarketbooks.org.

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and the Wallace Action Fund.

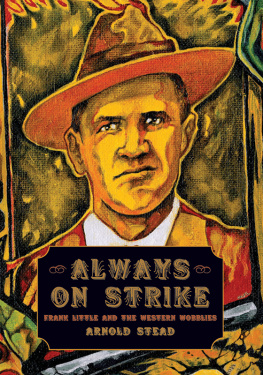

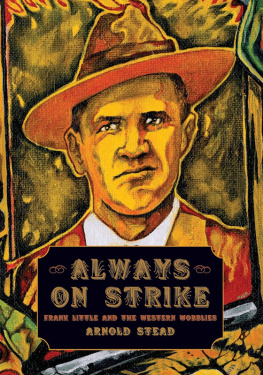

Cover design by Julie Fain. Cover image from a painting by Keith Seidel.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Contents

Introduction 1

Chapter One: The Western Wobblies 15

Chapter Two: The Free-Speech Fights 41

Chapter Three: Iron Miners, Harvest Hands,

and Oil Workers 69

Chapter Four: Urgency and Conspiracy 111

Chapter Five: Big Bill Haywood and Frank Little 143

Chapter Six: Three Western Wobbly Martyrs 155

Conclusion: Frank Little, Where Are You

Now that We Need You? 163

Acknowledgments 167

Sources 169

Notes 175

Index 183

Chapter One

The Western Wobblies

The roots of the western Wobbly are found in the placer miner, men who lived and worked in Utah, Nevada, Colorado, Montana, and Idaho during the latter half of the nineteenth century. He was a prospecting miner. His basic tool, a wash pan, allowed him to sample creek beds and other locations for precious metals. If he found something worth his trouble, he set to work building a rocker with hammer, nails, wire, other simple items he carried in his pack, and whatever wood he could find. Occasionally a placer miner struck it rich, like Marcus Daly, one of the founders of Anaconda Copper Company, who began as a prospector. Usually a placer miner made little more than a bare living, but he was his own man. Then the scent of money and cheap labor brought mining companies into the West. Melvyn Dubofsky speaks of industrial cities rapidly replacing frontier boom camps and heavily capitalized corporations striking up where placer miner/prospectors had been. With the arrival of the corporations, mining became a massive industrial undertakening, requiring railroads, milling and smelting facilities and a host of capital. By the time Frank Little was born (most sources say 1879 while a few others say 1880), many so-called frontier-mining settlements were anything but frontier.

Resentful and ready to rebel, the miners saw themselves as victims of an invasion by men with full bellies and soft hands, representatives of the real capitalists, who seldom came west and, when they did, were very unlikely to confront any miners face to face. These toadies of capitalist power smelled of cologne and threw around ten-dollar words as they might have pocket change. Condescending and sweet smelling, they had come to the West with dollar signs in their eyes. But let their swagger take them too far and a westerner with clenched fists and a dog-off-his-leash gleam in his eyes step too close to those condescending smirks and the swagger began to wobble at the knees, the voice suddenly cracked, and the face too often presented an obscenely frightened smile. That fear told the westerner somewhere, not so very deep inside, the easterner was empty. The invaders were on strange ground while the miners were at home, sure of their necessary place in the scheme of things, at the center of which was their independence and mining. I do not mention freedom because as one of the men might have told you: If a mans got his independence, what he digs is his own and he goes his own way. And if that aint freedom, I dont know what youd call it. Working for wages is nothing but slavery without the whip.

A placer miner commonly wore a pistol on his hip as protection against bandits, renegades, claim jumpers, and wildcats. A few sticks of dynamite could be found in his pack. When he went into town for supplies, he often indulged in a bottle of whiskey and a woman, or a game of stud poker, or maybe a good old-fashioned brawl just to take the edge off. You have no doubt seen a version of the character I am describing in any number of western movies and television. Gun Smokes Festus comes to mind. He might treat himself to clean sheets, a hot bath, and a soft bed, but not so often as to get the habit. For a placer miner, a wife and children were at best consolation prizes and at worst traps to be avoided. A wife and family usually destined a man to the necessity of working for wages. Sidestepping those kinds of traps could be difficult, but it was at least something a man had some control over. The mining companies threw a much wider and far tighter net. By the beginning of the twentieth century, if you wanted to make a living as a miner you worked for a company. Consequently an attitude developed: What choice have I got? A mans got to keep body and soul together. But working for wages only took care of the body. The soul is another matter entirely, and for these men it was not being nourished by a church. The food it cravedindependencehad been taken away by the mining companies. From most miners point of view only a Scissor Bill, a worker who accepts anything and everything the boss visits upon him, could be anything but restive and resentful.

The men who founded the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in 1893 in Butte, Montana, were figuratively and in some cases literally the sons of placer miners. They embraced the agenda products for all, profits for none. They had no desire to be a business union, interested exclusively in better pay, safer working conditions, and shorter working hours. Instead, the WFM wanted an end to the wage system entirely. The union echoed the cowboy mottoAnythings better than wages. In fact, Big Bill Haywood briefly attempted to organize cowboys.

In a discussion of anti-intellectualism among US socialists during the opening decades of the twentieth century, Pulitzer Prizewinning historian Richard Hofstadter accuses western Socialists of adapting a veritable proletarian mucker pose. He writes:

The most extreme anti-intellectual position in the partya veritable proletarian mucker posewas taken not by the right wingers nor by the self-alienated intellectuals but by Western party members affected by the IWW spirit. The Oregon wing was a good example of this spirit. The story is told that at the partys 1912 convention in Indianapolis the Oregon delegates refused to have dinner in a restaurant that had tablecloths. Thomas Sladden, their state secretary, once removed the cuspidors from the Oregon headquarters because he felt hard boiled, tobacco-chewing proletarians would have no use for such genteel devices.

One wonders how not wanting to eat off tablecloths in a public venue is anti-intellectual. Isnt it more likely the Wobbly-influenced Westerners objected to the tablecloths because they were not accustomed to them in so public and commercial a setting? Their experience of eating with tablecloths would have been on special occasions in an intimate, family setting. To break bread on a tablecloth under the circumstances described by Hofstadter could very well have been viewed by those workingmen as a betrayal of something they held dear. Likewise, Hofstadters use of the expression proletarian mucker demands some interrogation; specifically his choice of the word mucker, which Websters New World Dictionary (Third Edition) defines as [slang] a coarse or vulgar person, esp. one without honor; cad. In defense of so severe an epithet one expects more than two anecdotes; the first of which implies that rejecting the use of tablecloths is somehow dishonorable and anti-intellectual, while the second tells us far more about Thomas Sladdens expectations than it does about the attitudes of the workers in question. A sense of how deep class-cultural frictions and prejudices run renders itself visible when a thinker of Richard Hofstadters caliber rather off-handedly issues so harsh a judgment.

Next page