This is indispensable reading for anyone interested in representations of espionage in the Cold War and beyond.

Sara Jones, author of The Media of Testimony: Remembering the East German Stasi in the Berlin Republic

In these fascinating papers we see some of the insights gained from new literary readings of those [secret police] files, and new artistic representations of those classic Cold War figures: spies, secret police officers, and informers. A revelatory collection!

Katherine Verdery, Julien J. Studley Distinguished Professor, Graduate Center, City University of New York

Using fascinating, specific examples that make observers and the observed come alive in the readers mind, Cold War Spy Stories from Eastern Europe reveals the dynamic power play among multiple parties who constituted the oppressive political web throughout Eastern Europe and the USSR during the Cold War.

Susan Signe Morrison, professor of English at Texas State University

A great intervention by a team of experts equipped to deliver a much needed comparative perspective.

Stephen Parker, author of Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life

Presenting a gallery of well-chosen portraits of secret agents who worked for communist East German, Romanian, and Soviet surveillance agencies, this book illuminates the tenuous relationship between memory, discourse, and politics, mediated by the extant secret archives and movies. The chapters document Cold War spies whose complex lives and morally questionable choices enhance our understanding of life under communist dictatorship.

Lavinia Stan, professor of political science at St. Francis Xavier University, Nova Scotia

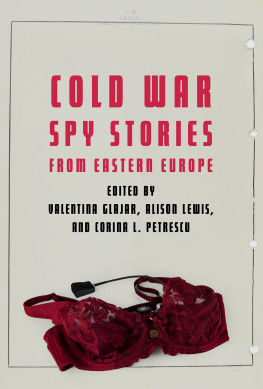

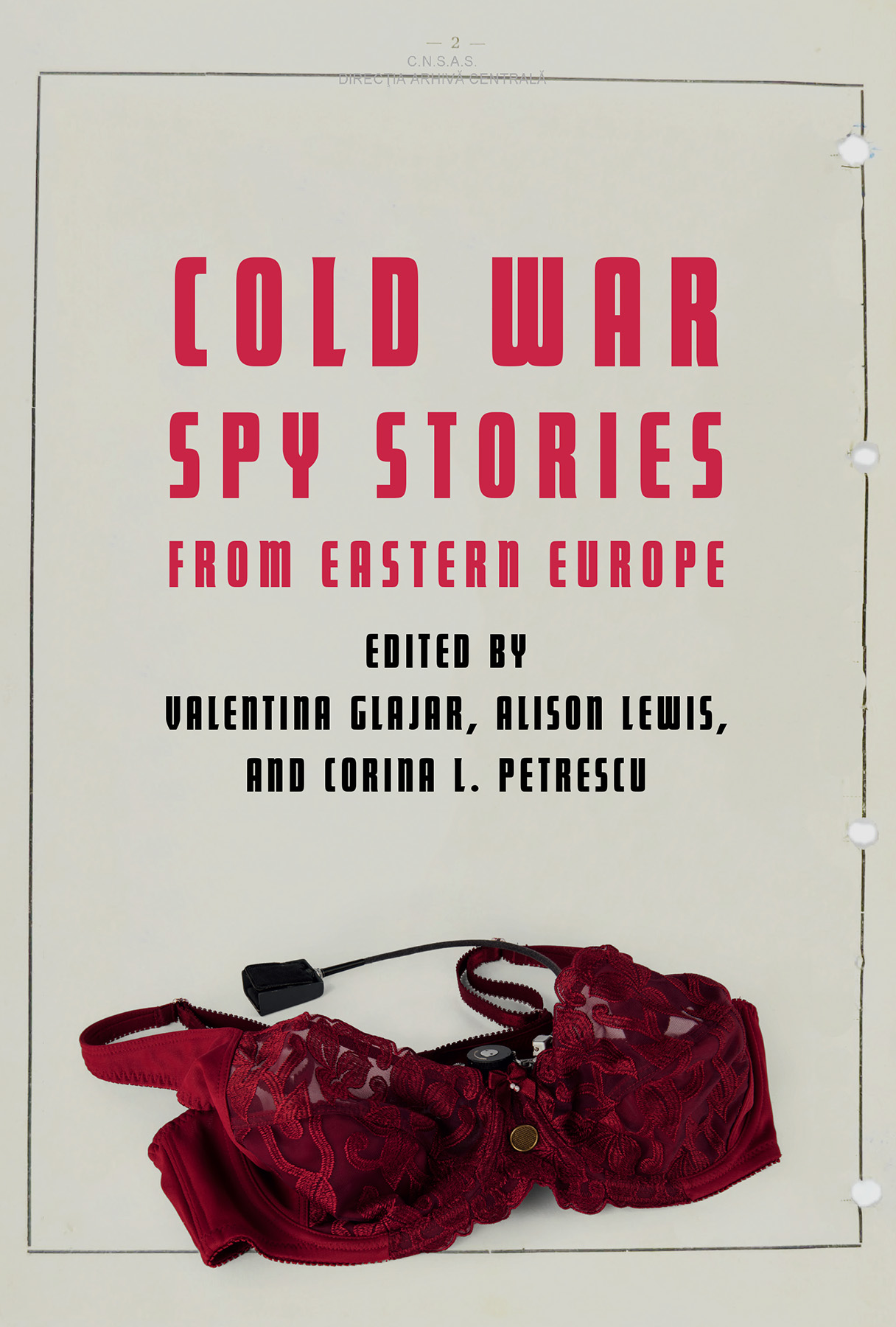

Cold War Spy Stories from Eastern Europe

Edited by Valentina Glajar, Alison Lewis, and Corina L. Petrescu

Potomac Books

an imprint of the University Of Nebraska Press

2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image courtesy of the German Spy Museum Berlin.

All rights reserved.

Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Glajar, Valentina, editor. | Lewis, Alison, 1958 editor. | Petrescu, Corina L., editor.

Title: Cold War spy stories from Eastern Europe / edited by Valentina Glajar, Alison Lewis, and Corina L. Petrescu.

Description: Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018036252

ISBN 9781640121874 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781640121980 (epub)

ISBN 9781640121997 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640122000 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : EspionageEurope, EasternHistory20th century. | EspionageCommunist countriesHistory. | SpiesEurope, EasternHistory20th century. | SpiesEurope, EasternBiography. | Cold War. | Espionage in literature. | Espionage in motion pictures. | Cold War in literature. | Cold War in motion pictures. | Europe, EasternHistory19451989.

Classification: LCC DJK 50 . C 65 2019 | DDC 327.1247009/045dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018036252

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Sergio and Aki

Contents

Alison Lewis, Valentina Glajar, and Corina L. Petrescu

Valentina Glajar

Mary Beth Stein

Alison Lewis

Corina L. Petrescu

Julie Fedor

Jennifer A. Miller

Axel Hildebrandt

Carol Anne Costabile-Heming

Lisa Haegele

Cheryl Dueck

Valentina Glajar and Corina L. Petrescu would like to thank CNSAS for its continued support of their research of Romanian secret police files. Special thanks go to Silviu Moldovan, who tirelessly deals with their requests and exceeds their expectations every time they visit the Securitate archives in Bucharest. Alison Lewis would also like to thank the BS t U for allowing her access to the Stasi files.

Corina L. Petrescu is grateful to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for its generous financial support that afforded her the means to conduct the research and the leisure to work on this project. Valentina Glajar would like to acknowledge funding from her institution that helped produce this volume. Alison Lewis would like to acknowledge the financial assistance of the Australian Research Council and its Discovery Project scheme, which funded the research.

Alison Lewis, Valentina Glajar, and Corina L. Petrescu

If the Great War belonged to the soldier in the trenches, the Cold War surely belonged to the spy: the shadowy soldier on the invisible front fighting behind the scenes in the service of Communism or the free world. During the Cold War, spy stories became popular on both sides of the Iron Curtain, capturing the imaginations of readers and filmgoers alike, as secret police outfits quietly went about their business of espionage and surveillance, under the shroud of utmost secrecy. Curiously, in the postCold War period there are no signs of this enthusiasm diminishing. Indeed, the advent of what is often called a postpolitical world order (cf. Takale 2016) and a politics without frontiers (Laclau and Mouffe 2001, xiv) has opened up exciting opportunities to tell these spy stories anew. We can now recompose these tales of collusion and complicity, betrayal and treason, right and wrong, good and evil in light of new ways of thinking as well as new evidence from declassified archival sources. We can read Cold War modes of storytelling differentlyremaining attentive to the fictional subtexts in factual spy narratives and the factual underpinnings of fictional works about espionage.

With the opening of the secret police archives in many countries in Eastern Europe, moreover, comes the unique chance to excavate forgotten accounts of espionage and tell them for the first time. Spy stories told through the prism of the secret police conveyed as file stories (Glajar 2016, 57)about the top-secret lives of intelligence officers, their agents or informers as well as their targetsrepresent one distinct mode of Cold War spy story, a mode based on factual or forensic truth (Lewis 2016, 215) but undergirded by ideological fantasies and paranoid fictions. The opening of the files has also led to the rediscovery of curious or enigmatic espionage events, which are being told in interconnected multimodal webs of narrationwhether as memoirs of notorious spymasters or as recent fictions and feature films about complex and hitherto unexplained Cold War incidents. Finally, the opening of the Iron Curtain has challenged old Cold War antagonisms such as the friend/foe binary, which is in turn recasting espionage scripts and the very character of the spy and double agent, as witnessed in new styles of spy films such as Bridge of Spies (2015) and television dramas such as Weiensee (2010), The Americans (201318), Deutschland 83 (2015), and Berlin Station (2016) made for a global, postpolitical audience.

This book is concerned with the stories we tell about lives lived during the Cold War. Stories are, according to Paul Ricoeur, what mediates between the past and the present and a fundamental means of how we make sense of experience. The act of narrating is how we assimilate a life to a history (Valds 1991, 425). Put simply, without stories, lives would remain untold and hidden in dusty archives. While Ricoeur speaks here about the world of fiction, as that which helps to make lifein the biological sense of the worldhuman (Valds 1991, 425), his analysis of the relation between stories and lives can be extended to all forms of storytelling from the stories of history and personal memory to the stories in secret police files. Individuals seem entangled in stories that happen to them, according to Ricoeur (Valds 1991, 435), even historical individuals, and through their telling of stories we can understand them. Narration, narratives, and plots are fundamental ways of making sense of the world: By means of the plot, goals, causes, and chance are brought together within the temporal unity of a whole and complete action (Ricoeur 1990, ix).

Next page