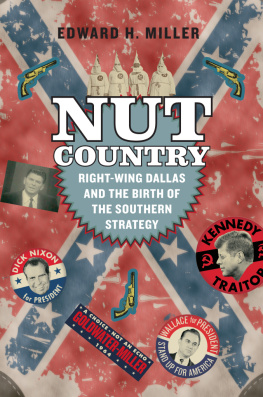

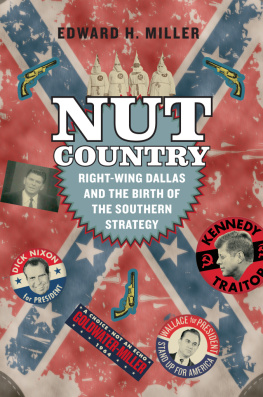

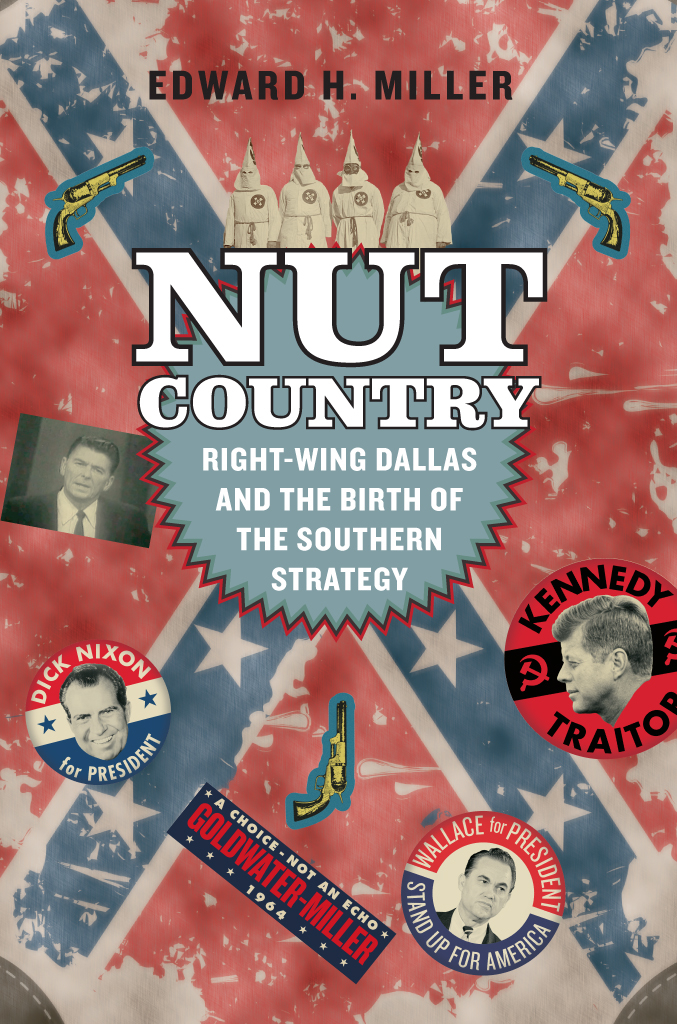

Nut Country

Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy

Edward H. Miller

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

Edward H. Miller is assistant teaching professor at Northeastern University Global.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-20538-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-20541-0 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/ 9780226205410.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Edward H. (Edward Herbert), author.

Nut country : right-wing Dallas and the birth of the Southern strategy / Edward H. Miller.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-20538-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-20541-0 (ebook)

1. Republican Party (Tex.)History20th century. 2. Right-wing extremistsTexasDallas. 3. ConservatismTexasDallas. 4. Dallas (Tex.)Politics and government20th century. 5. Southern StatesPolitics and government1951. I. Title.

JK2359.D35M55 2015

324.273409'045dc23

2015010761

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

On Saturday, an honor guard kept vigil over Kennedys body, which lay in state in the East Room of the White House. On Sunday, amid muted drumbeats, a horse-drawn caisson slowly moved the presidents body up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol rotunda. Kneeling beside the casket, the presidents thirty-four-year-old widow kissed the flag draped over her husbands coffin. A quarter of a million strongmany crying or holding back tearsshuffled by. On Monday, six white horses drew the carriage containing the casket to its final resting place in Arlington National Cemetery. A riderless horse named Black Jack restlessly followed and John F. Kennedy Jr., on his third birthday, saluted his father one last time. President Kennedys body lay motionless in the coffin.

But some were convinced it would not be there long: Kennedy was going to rise from the grave and become the Antichrist. Those who believed this tended to be devout premillennial dispensationalists who held that the Bible foretold in detail the chronology of the end of the world, and that the Antichrists arrival marks the Rapture, the beginning of the Tribulation, a seven-year period that ends with the final battle of Armageddon. For them, the setting was perfect for the advent of the Antichrist. Via the still new medium of television, the world seemed to be watching, and many heads of state were present in Washington, DC. Many signs suggested that Kennedy was the beast described in the book of Revelation. Beyond his head wound, Kennedy had been a member of the Catholic churchthe Whore of Babylon according to some Protestant readings of Revelation, an institution destined to play a crucial role during the Antichrists rule and reign.

On the other end of the Dallas Republican Party from Hunt was Henry Neil Mallon, the quintessential Dallas moderate conservative Republican.

During the early 1950s, Mallon became deeply concerned about Hunt and his burgeoning media empire. In 1953, Mallon wrote about Hunt to his best frienda Yale classmate, fellow member of the Skull and Bones secret society, and US senatorPrescott Bush, the father of George H. W.

Mallon saw the need to counterbalance Hunts message and, as a result, became more involved in local politics. He established the Dallas Council on World Affairs, a local center-right group that scheduled speakers and discussions. He attended Republican Party events, making generous contributions to moderate conservative Republican candidates and throwing his support behind Barry Goldwater. In his public pronouncements, Mallon advocated the importance of home ownership and lowering tax rates to 25 percent for the most affluent Americans. He shaped the corporate culture at Dresser Industries (which would later become part of Halliburton), hiring many moderate conservative Republicans, including George H. W. Bush, who named his third son, Henry Neil Bush, after Mallon. At Dresser, Mallon created a corporate culture that spoke reverentially of the ability of the free market to allocate wealth efficiently and fairly without government interference.

The example of H. N. Mallona Republican stalwart who felt threatened by the rise of ultraconservative Republican activity in Dallas between 1953 and 1963 and was motivated to pursue a brand of relative centrismillustrates the main argument of Nut Country. This book focuses on relationships and ideological exchanges between the ultraconservative and moderate conservative Republicans of Dallas, Texas, and shows how ultraconservatives like H. L. Hunt, who received widespread national media attention in the 1950s and 1960s, served as important catalysts for the diffusion of conservative ideas across the entire right wing of the American political spectrum. Hunt and other ultraconservatives provided the impetus behind much of the conservative activism of the era, among both moderate and ultraconservative Republicans. They not only pushed moderate conservatives into an increasingly active role in 1950s and 1960s Dallas Republican politics, they also radicalized the right wing of the national party and forced the mainstream to embrace some of their fringe ideas.

Ultraconservative Republicans offered moderate conservative Republicans cover in constructing political identities: by labeling ultraconservative doctrines extremist, the moderate conservatives could position themselves at the local and national levels as comparatively respectable and credible. Ultraconservatives like Hunt received the lions share of the brickbats and catcalls from the American national media. By comparison, more moderate conservative activists, intellectuals, and politicians like H. N. Mallon, Congressman Bruce Alger of Dallas, Senator John Tower of Texas, and Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona often remained shielded from attacks and could develop policies and political styles that mirrored, albeit subtly, those of the fringe.

Nut Country shows that ultraconservative Republicans were more essential to the rise of the Right than recent historians have appreciated. Many of the original scholars studying American conservatism acknowledged ultraconservatives but largely dismissed the Right as suffering from status anxiety, burdened by irrationality, possessing a paranoid style, or simply reacting to social or political backlash.these ultraconservatives were even more important than the moderate conservatives.

This book also presents a novel interpretation of the Republican Southern Strategy. As many scholars have shown, Republican leaders like Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan broke the Democratic Partys hegemony in the Solid South and segments of the North by capitalizing on the reactions of white voters to events of the 1960s, when anxieties about the counterculture, the decline of traditional sexual mores, the decrease in union membership, and the new tendency of whites to see themselves as home owners, taxpayers, and school parents rather than workers, were reshaping their political thinking. Even more crucial, the Democratic Partys support for affirmative action, school busing, and welfare made these Northern and Southern white voters conclude that the party no longer protected their