But still, like dust, Ill rise.

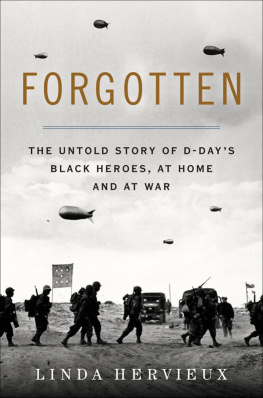

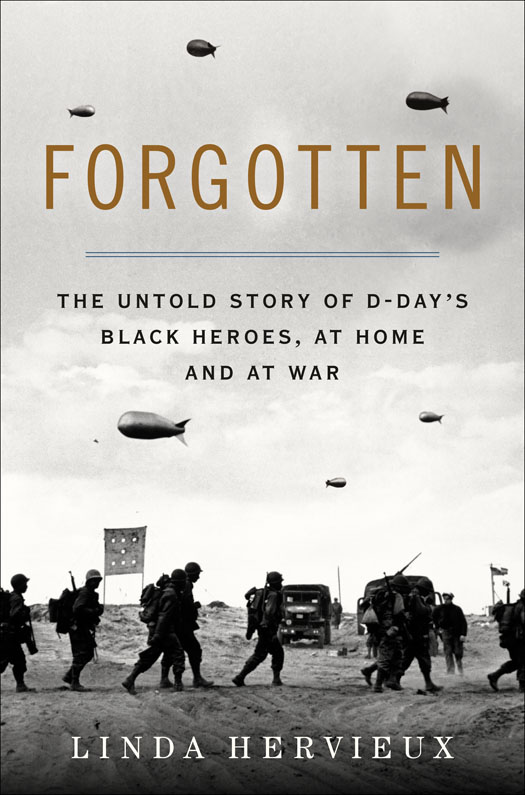

I ve been waiting for someone to call me for fifty years, Wilson Caldwell Monk told me on the phone on a warm spring day in 2010. A year of reporting and digging had brought me to Monk, a master sergeant during World War II in charge of the bullet-shaped balloons floating over the Normandy beaches after the Allied invasion on June 6, 1944. The balloons formed a defensive line in the sky, shielding the men and matriel from German planes. They had been set up there by the men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only African American combat unit to land on D-Day. I was calling Monk because I had committed myself to telling the story of the 320th, a story largely lost to history, even amid the thousands of books, films, and oral histories of what some consider the most important day of the twentieth century.

I first heard about Americas barrage balloon flyers in June 2009 while reporting on the sixty-fifth anniversary of D-Day for the New York Daily News. William Garfield Dabney, a veteran from Virginia, had traveled to France to receive the Legion of Honor, that countrys highest award. Organizers said Dabney was likely the only member of the 320th still alive. It turns out nobody had checked.

I knew nothing about barrage balloons, beyond seeing iconic images of them floating over the Normandy coast after the Allied invasion. I had thought little of the presence of African Americans on those blood-soaked beaches. Even many military historians believed that the only black soldiers to land on D-Day had lent their muscle to labor units and other support work. Not that the contributions of these men were unimportanton the contrary. Of the nearly two thousand African Americans who participated in the greatest military operation the world had ever seen, the majority were service troops who performed heroically as stevedores and truck drivers, unloading and transporting crucial supplies. On the beaches, they carried the wounded to safety and buried the dead.

Yet only one highly trained black combat force landed on Omaha and Utah Beaches. They would struggle to stay alive and get their balloons aloft, under withering German fire. The 320th medics would see glory, credited with saving scores of men wounded in the early hours of the invasion. One of them, a college student twice hit by shrapnel named Waverly Woodson, was recommended for the Medal of Honor, the United States highest decoration for valor. It was an award he would never receive, and I wanted to know why.

Soon after the invasion, the story of the balloon troops extended far beyond their berths on the beaches. They made headlines in the crusading black newspapers of the day, in the white press, and in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes. Under pressure to give black soldiers more meaningful roles, the army sent out glowing reports praising the 320th. It seems the whole front knows the story of the Negro barrage balloon battalion outfit which was one of the first ashore on D-Day, wrote a war correspondent in July 1944. They have gotten the reputation of hard workers and good soldiers. That dispatch was sent to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who later that month issued a commendation praising the battalion for carrying out its mission with courage and determination. Ike said the unit proved an important element of the air defense team.

Yet time had stripped away traces of the men and their balloons.

When I expressed interest in their story, I was warned off. You wont find enough to write a book about them, one military historian told me. Other experts agreed. Another suggested I write about that black tank unit instead, a reference to the 761st Tank Battalion, the hard-fighting Black Panthers, who helped Gen. George S. Patton roll to victory across Europe.

Like the 761st, other black units have been chronicled in print and film, among them the inspiring Tuskegee Airmen, whose exploits were ignored for decades. Even the Red Ball Express, the group of indefatigable truckers who supplied the Allied front in France, has its place in history. But so little had been written about the men of the 320th, even in the military history books in which they should appear. And what about those balloons? I was intrigued.

To be sure, I was an unlikely candidate to write a book about the armys balloon flyers. I began this project with little knowledge of warany war. And if I had ever learned about it to begin with, I had long forgotten that the U.S. military was segregated in World War II. It was a Jim Crow system of extraordinary breadth underpinned by virulent racism that mirrored life in many parts of my own country. As a white woman from Massachusetts, I was angry that the history classes Id taken from grade school through college had downplayed, or even ignored, this shameful reality. I was also aware of my own failure to educate myself about the African American experience. So, bringing that baggage with me, and hoping I was qualified to tell their story, I set out to find veterans of the 320th. These men would be in their nineties, and time was running out.

In the end, I would interview twelve men from the battalion, and the families of several others. Some of the men had never spoken of their wartime adventures until I showed up at their doors. Some of their children had no idea that their fathers had been at D-Day. Over the next four years, I repeatedly visited Monk; Dabney, the man honored in France; and a third veteran, named Henry Parham. Their wives and children became my friends. These men are the main subjects of this book, but they are not alone. I was fortunate to find other memorable 320th men who shared their stories with me, including Samuel Mattison, a charming raconteur from Columbus, Ohio; soft-spoken Willie Howard from Olivia, North Carolina; and the future preacher Arthur Guest from Bonneau, South Carolina. Thanks to interviews Waverly Woodson gave before his death in 2005, we have a glimpse of the hero medic from West Philadelphia.

Finding the men of the 320th wasnt easy, but unearthing records about their mission was even more difficult. There was little beyond a bare-bones history of the unit in army archives. I spent months trolling for more at archives around the United States and, later, in Britain. The information I found traced the broad strokes, but the details were exceedingly tough to nail down. I couldnt complain; Id been warned. In the story of the 320th men was another story to be told, that of the lives of African Americans during the heyday of Jim Crow. The men I spoke to recounted how their lives had profoundly changed when they entered the army, leaving home for the Deep South (training at Camp Tyson, Tennessee), where they were subjected to levels of racism more virulent than many had ever experienced.

Their subsequent journey to Europe took them to New York City, where they boarded a converted passenger liner and set off on a harrowing trip across the North Atlantic, during which German U-boats hunted for ships just like theirs. Finally, they landed in Britain, where, to their delight, they were welcomed by people who had never heard of segregation. The freedoms they experienced there were life-changing. In villages in Wales and Oxfordshire, they lifted pints in pubs alongside white men for the first time and danced with white girls. This warm welcome infuriated many white American soldiers, particularly southern ones, who tried, and failed, to poison the Britons against the Negroes.