Copyright 2018 by Rachel Devlin

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: May 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Names: Devlin, Rachel, author.

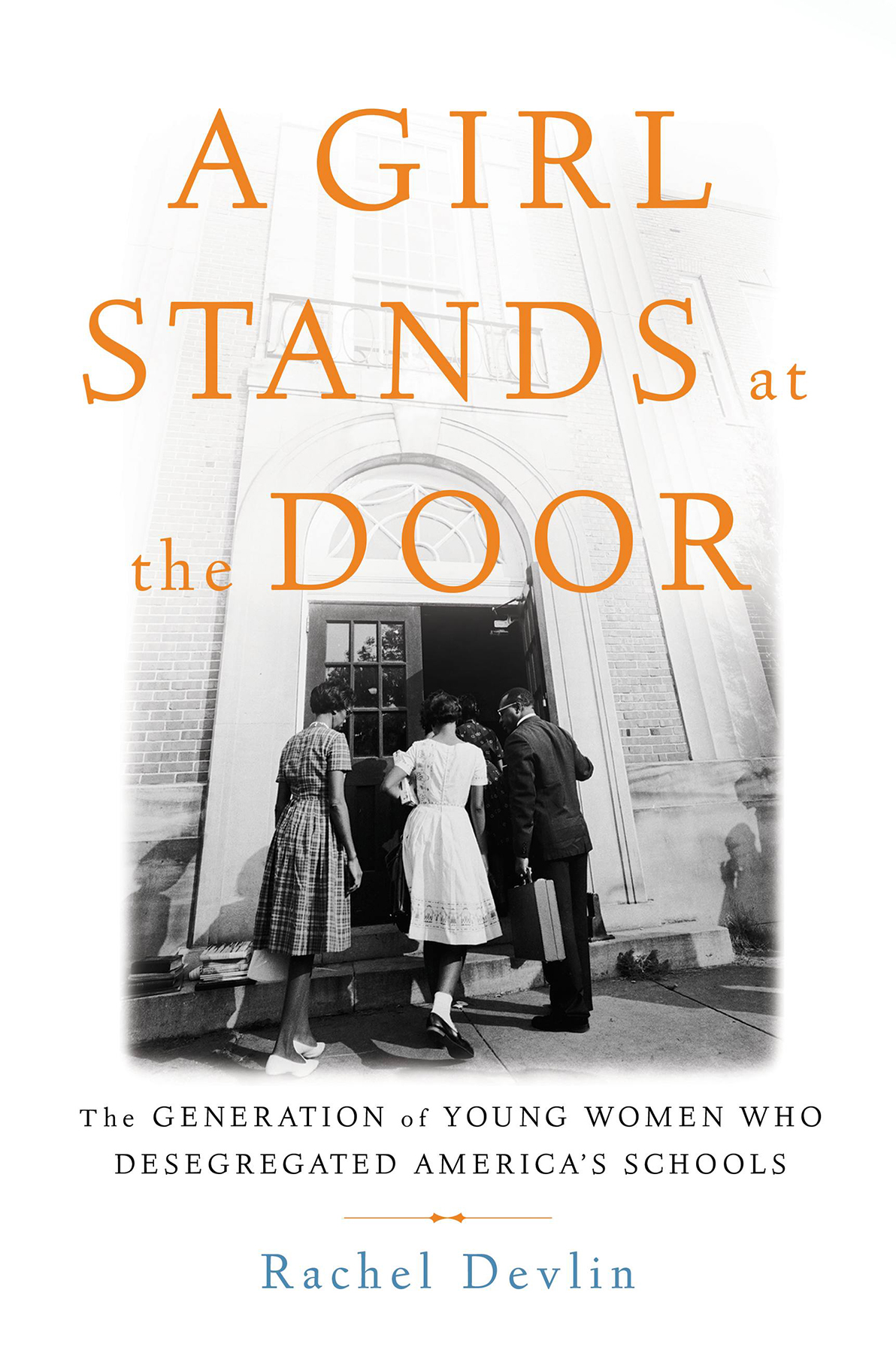

Title: A girl stands at the door : the generation of young women who desegregated Americas schools / Rachel Devlin.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017055188 (print) | LCCN 2018016453 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541616653 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541697331 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Segregation in educationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Discrimination in educationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | School integrationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Educational equalizationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | African American girlsEducationHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC LC212.52 (ebook) | LCC LC212.52 .D48 2018 (print) | DDC 379.2/63dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017055188

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-9733-1 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-1665-3 (ebook)

E3-20180406-JV-PC

Before reading this I would have imagined that nothing new could be said about the struggle to desegregate schoolsI would have been wrong. Rachel Devlin has uncovered a neglected history of how parents and, importantly, children braved rejection, hostility, even assault to insist on their right to a decent education. Possibly most surprising, these courageous students were mostly girls, a finding that challenges some assumptions about risk-taking behavior. Not least, the book is a great read.

L INDA G ORDON , author of The Second Coming of the KKK

In Memory of Betta Jean Bowman 19472016

Rubye Nell Singleton Stroble 19472010

O N THE MORNING OF A PRIL 13, 1947, fourteen-year-old Marguerite Daisy Carr went with her father to Eliot Junior High School, the white middle school closest to her home in Washington, DC, and attempted to enroll. The principal, tipped off that she was on her way, met her on the steps. As she stood facing him, the white students pressed up against the windows to see what would happen. Across the street, teachers, students, janitors, the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), and the principal from Carrs black middle school, Browne Junior High, lined the sidewalk. To their minds it was something made up, something fantastic. But here this child is just coming on, Carr, now Marguerite Carr Stokes, remembers. In gauging this situation, she relied on what her parents had taught her about how to behave in the presence of adults. And so, she says, I smiled nicely, because I knew how to act in polite company. When the principal told her you dont want to come here, she responded, respectfully but firmly: I do want to come to this school. Carrs response met the contradictory requirements inherent in such confrontations. She smiled, a sign of social reciprocity, trustworthiness, a willingness to engage. On the other hand, she combatively, courageously talked back to a white adult, announcing her intention to break down the legal strictures and social customs that barred her from the newly built citadel of learning two blocks from her home.

Marguerite Carr and her father, James C. Carr, sued Eliot Junior High, and her lawsuit, Carr v. Corning, was one of almost a

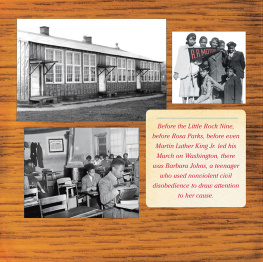

After the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board in 1954, the pattern continued: in the most contested school desegregation battles in the Deep South, girls and young women vastly outnumbered boys as the first to attend formerly all-white schools. In Little Rock in 1957, six girls and three boys famously went forward as the Little Rock Nine. In New Orleans in 1960, four girls entered the first grade at previously all-white schools. In 1963, seven girls and three boys desegregated the lower and upper schools in Charleston, South Carolina, and in the same year twenty-two girls and six boys desegregated the high schools in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In Albany, Georgiasite of intense civil rights protests and the mass jailing of young people in the early 1960ssix young women desegregated Albany High School in 1964. Whether applying to graduate schools in the 1940s, filing lawsuits with their parents in the immediate postwar years, or volunteering to desegregate high schools in the Deep South after Brown, girls and young women disproportionately led the way in the battle to desegregate American public schools in the mid-twentieth century.

School desegregation could not have happened without those who were willing to put themselves forwardthe guinea pigs, as they sometimes called themselveswilling to incur the wrath of

The story that has been told about Brown is that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the engine behind the cases: desegregation cases began to be filed in 1950 only after the NAACP made them its top priority, litigants were recruited and vetted, and many if not most plaintiffs were prevailed upon by NAACP lawyers to file desegregation cases. Following Richard Klugers timeline in his magisterial 1975 book Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black Americas Struggle for Equality, the history of Brown is toldin countless museum exhibits and textbooksas a story that began in Clarendon County, South Carolina, with Briggs v. Elliott, then took a detour through Texas with the law school case Sweatt v. Painter, found its way to a Charleston federal appeals court, where Judge Julius Waties Waring contributed a galvanizing dissent in 1951, and then proceeded with cases in Delaware, Virginia, Kansas, and Washington, DC, all filed between 1949 and 1951.

Much about this tidy conceptualization, however, is belied by the geography of the many previously unknown postwar cases and the manner in which they came to the attention of the NAACP. Indeed, the NAACP had little to do with the sudden rash of cases that presented themselves all at once in the aftermath of World War II. As Thurgood Marshall complained in 1968,

People are not yet convinced that we never had a program from the beginning to the end there was no plan on any of these cases. None. The best proof of it is that once we won the law school and the graduate school the next case should have been college, then junior college, then high school, then elementary school. It ends up the next case was elementary school. Well obviously there was no plan. And we, we were kind of peeved. We didnt really want it. We didnt want it, but we had it. We wanted to bring it down, bring it down one to the other. We had been going at it this long, lets take a couple more years. Then all of a sudden, here we go.