ELAINE M. BAPIS

For Nick and my precious family: Often neglected but never forgotten during these last months of cure and creation.

It takes a team to continue on difficult journeys. Thank you Bob Goldberg at the University of Utah Department of History for your consistent, critical commentary and unwavering enthusiasm for this project, despite the often tedious and overwritten drafts. Your experienced eye contributed to improvements at every stage in the process. I am grateful to Mary Strine, Eric Hinderaker, William Siska, and Rebecca Horn whose support and encouragement came unfailingly through many provocative questions and suggestions. Thank you Christine Pickett at the University for your diligence, your enthusiasm, and your excellent reading talent. Thank you Margaret Herrick and North Baker libraries. Madeleine at the Library of Congress made my research delightful.

Part of chapter V was originally published as "Easy Rider: Landscaping the Modern Western" in The Landscape of Hollywood Westerns: Ecocriticism in an American Film Genre, edited by Deborah A. Carmichael, published in 2006 by the University of Utah Press, and is used with permission.

As in every written project, there is a group of people that fills in the trail to publishing. For me it is the professors in the English Department at the University of Utah whose encouragement in my literary development is responsible for the beginnings of my professional life. I would like to thank Meg Brady, Steve Tatum, and Kathryn Stockton for giving me confidence in my early years. My friends and relatives offered endless encouragement; thank you for loving film with me. A special thanks to Sean Mooney for helping me keep my perspective, to Tom Harvey and Liza Nicholas for the provocative happy hours and the critical commentary, to Markle Fair for the special conversations, to Maria Mastakas and Alethia for saving me at the eleventh hour. My love of ideas began with my parents' faith in education. I am grateful for their insistence on academic learning. A special recognition goes to my father who was not able to see this completed. My deepest and heartfelt gratitude goes to my children for their patience during the most trying tasks and for their happiness over the finished product. In particular, thank you Nick, Michael, Eleni, Alethia, and Chris for always checking in and for your unwavering belief in me. Maria and Georgia, thank you for bringing such love into the world.

vi

INDUSTRY AND AUDIENCES

GENERATION

GENDER

ETHNICITY

Chapter 213

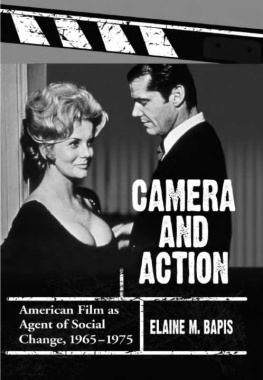

This study examines the changes in the American film industry, audiences, and feature films during the years 1965-1975. With transformations in production codes, new adjustments in national narratives, a rise in independent filmmaking, and a new generation of directors and producers addressing controversial issues on the mainstream screen, film was part of the processes of social change that defined these years. Filmmakers advanced a new mantra in the business of Hollywood. Anything that was "new, now, and real" would be material for the lens and any story that went through the camera had to "tell it like it is."

Many baby boomers thought of film as an agent for social activism concerning such issues as the generation gap, the counterculture, masculinity, women's liberation, and multiculturalism. Rather than comparing history to film and correcting data, Camera and Action places film inside historical processes. Using generation, gender, and ethnicity as categories of analysis, this work adds to the history of film as well as to the literature on representation, identity construction, and cinema as a visual site of debate.

Ten motion pictures stand out as representations of the important role that film played for many Americans from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. The Graduate, Alice's Restaurant, Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy, M*A *S*H, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Carnal Knowledge, Little Big Man, The Godfather, and The Godfather: Part II have become cinematic records of the cultural forces shaping American society during these turbulent years. Nine of the ten films have maintained an enduring legacy as icons in popular culture. The single film McCabe and Mrs. Miller, a box office flop, is included because it has maintained a critical status in academic studies and allows an important statement about the parameters of discourse at the time. These pictures memorialized a period when adversarial and unsettling narratives were a popular form of advocacy. In their success and qualified survival, each film helped define our relationship to the meaning of the late sixties and early seventies as historical reference points.

With transformations in the American film industry and the changing composition of audiences, viewer expectations became a necessary part of the story. The Graduate (1967) staked claims of generational authority. Two years after its release, Arthur Penn turned to the counterculture to show splits within the younger generation. Penn's Alice's Restaurant (1969) exemplified the Americanness of the hippie phenomenon and its use as a site of liberation. That same year, Easy Rider (1969) arrived front and center in America to meld new counterculture men with the men of Westerns past. This experimental film registered the new taste in cinematic pleasure with its box office success and subsequent iconic status.

When a faux cowboy and a street hustler in Midnight Cowboy (1969) entered the cinematic conversation, audiences learned of the impact of movies on male identity. The antiestablishment men in Robert Altman's M*A*S*H (1970) introduced a new image of the war hero in film. Altman returned to look at the Western's role in the construction of gender identity and authority in McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). This film critiqued the genre and tested the possibility for women's equal opportunity and treatment in formula narratives. Mike Nichols turned the tables on the gender debates in Carnal Knowledge (1971) to show that not much had changed between men and women.

Arthur Penn, in Little Big Man (1970), considered what the impact of Hollywood has been on Native American identity. His groundbreaker tried to "tell it like it was" in the old West. American cinema came full circle to the return of the genre with Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972). His "family affair" constructed Italian ethnicity as a quintessential American identity and included the European ethnic in the multicultural debates of the 1970s. The Godfather: Part II (1974) both questioned and participated in the ethnic resurgence in the larger society.