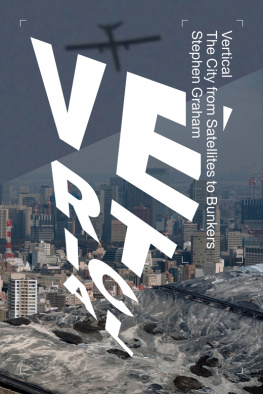

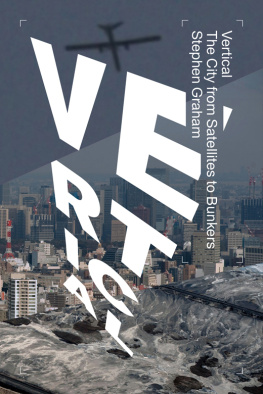

V

E

R

T

I

C

A

L

The City from Satellites to Bunkers

Stephen Graham

To my friends

This edition first published by Verso 2016

Stephen Graham 2016

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders for the images used herein. Verso and the author would like to extend their gratitude, and to apologise for any omissions, which, should we be notified of their existence, we will seek to rectify in the next edition of this work.

For permission to reproduce images we would like to thank the following in particular: David Coulthards car on the Burj Al Arabs helipad, courtesy of the Jumeirah Group ()

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-793-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-996-7 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-995-0 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Graham, Stephen, 1965 author.

Title: Vertical : the city from satellites to bunkers / Stephen Graham.

Description: Brooklyn : Verso, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016033169 | ISBN 9781781687932 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Cities and towns Growth. | Land use, Urban. | Space (Architecture) Social aspects. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Sociology / Urban. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Public Policy / City Planning & Urban Development. | ARCHITECTURE / General.

Classification: LCC HT371 .G69 2016 | DDC 307.76dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016033169

Typeset in Minion Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

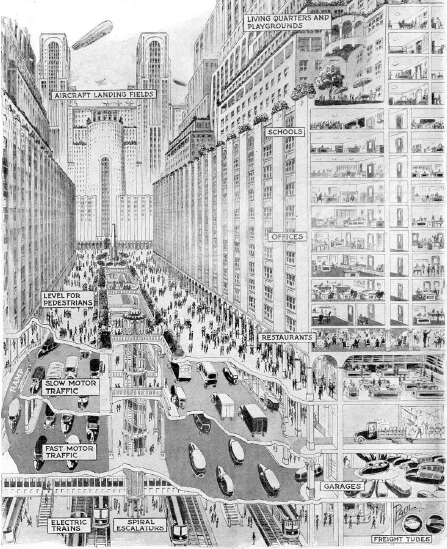

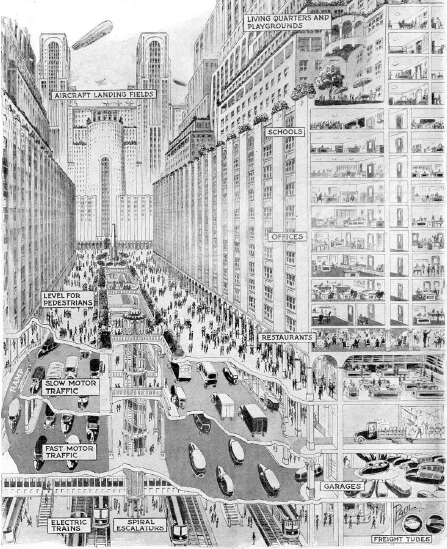

Vertical city: a 1928 image of the future by city planner Harvey Wiley Corbett published in the US magazine Popular Mechanics

What would happen if you took geographic thinking and instead of putting it on a horizontal axis, you added a vertical axis?

Trevor Paglen

My brain simply could not process what I saw. That tiny grey smudge, just visible far below to my right through the ice-specked Perspex, was Baghdad! As 200 travellers and holidaymakers around me sipped gin and tonics, delved into familiar episodes of Friends and The Simpsons, or played classic 1980s arcade games like Missile Command or Battlezone on in-flight entertainment systems, we were flying high above a full-on war zone.

Between us and the ground, complex military air operations were under way, coordinated from a bunker in our destination country linked, since the previous August, to newly established air traffic controllers in their own fortified complexes in Baghdad itself. Each day, around sixty commercial flights were being routed either over or around combat operations; these command centres were simultaneously organizing war and tourism within the same airspace.

The circuits of global capitalism and tourism and in the case of

And so to our stopover: Dubai. By chance, we were in town during the ultimate stage-managed urban spectacle: the opening of the worlds tallest building, the 830-metre Burj Khalifa. Here, rather unexpectedly, was a place that, like few others, hammered home the growing need to appreciate the vertical aspects of geography and urbanism: a centre of extraordinary vertical politics and vertical geographies.

Jet-lagged and dazed, we walked among excited crowds. We also enjoyed the vast fireworks display and lightshows emanating from the tower itself and the 30-metre, $225 million dancing fountains (the worlds tallest, needless to say). The fountains seemed especially lavish in a desert country with no real rivers, a collapsing or totally nonexistent ground water supply and the highest per-capita water consumption on Earth. As the towers and fountains have risen, so Dubais ground water level has plummeted by over a metre in the last twenty years. It would take centuries for this drop to be reversed, even with a complete cessation of usage.

We looked in awe at the most verticalised of cityscapes, ratcheted into the sky in a mere decade, rearing up from hundreds of miles of pancake-flat desert. It felt as though wed arrived on some vast stage set for a highly sanitised sequel to Blade Runner made by Disney. Everywhere we looked there were exalted proclamations that the Burj Khalifa, which snaked ever upward like a sci-fi icon, heralded, along with the many other new skyscrapers in the city, Dubais arrival as a world-class or global city.

Such towers are ultra-vain and some would say suspiciously phallic embodiments of the hubris of the super-rich. Despite the claim that high-rise construction is necessary to accommodate a burgeoning humanity, between 15 per cent and 30 per cent of their height the highest part, the so-called vanity height is so slim as to be capable of housing only lift shafts and services.

Such super-tall towers are catalysts designed to add value to vast malls and real-estate projects. And they are stage sets for media stunts designed to lubricate the worlds of tourism or hyperconsumption. Burj Khalifa is more the spike of luxury, than anything accessible the condominium level [rents] for $2,000 per square foot. Startlingly, the top 244 metres of the tower fall into the vanity height category the sole purpose of this part of the tower is to get the place into the record books.

Meanwhile, the sculpted, Thunderbirds-style helipad atop Dubais other famous new structure, the super-expensive, sail-shaped Burj Al Arab Hotel count those seven stars! is as much a global stage of bling as a place for the super-rich to land and take off. It has been used to stage-manage launches of Aston Martins and Formula 1 racing car teams, to play host to superstar tennis matches, and to accommodate Tiger Woodss golf demonstrations and product launches.

Also central to the spectacular vertical rise of places like Dubai are global flows of speculative investment as the cash-rich super-elite who profit most from global neoliberalism seek iconic vertical buildings in low-tax, unregulated enclaves as investment vehicles. In Dubai, as elsewhere, this process raises towers that are often not even fully occupied by people: while projecting their symbolic value to the world, they often house capital rather than humans. Brand Dubai is thus all about linking the rising forest of steel, concrete, aluminium and glass to a collective architectural fantasy, a phantasmagoria of supreme lifestyles, for consumers, tourists, speculators and elites orchestrated through the complex machinations of global finance, global airline systems and global geopolitics (as well as, less visibly, organized crime, money laundering, financing of terrorism and sex and people trafficking). Vertical metaphors saturate indeed constitute these narratives.