ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suzanne Brown-Fleming, historian, is the director of the Visiting Scholars Programs at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. She is also the author of The Holocaust and Catholic Conscience: Cardinal Aloisius Muench and the Guilt Question in Germany.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel

Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies

Documenting Life and Destruction

Holocaust Sources in Context

SERIES EDITOR

JRGEN MATTHUS

DOCUMENTING LIFE AND DESTRUCTION

HOLOCAUST SOURCES IN CONTEXT

This groundbreaking series provides a new perspective on history using first-hand accounts of the lives of those who suffered through the Holocaust, those who perpetrated it, and those who witnessed it as bystanders. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museums Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies presents a wide range of documents from different archival holdings, expanding knowledge about the lives and fates of Holocaust victims and making these resources broadly available to the general public and scholarly communities for the first time.

BOOKS IN THE SERIES

- Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume I, 19331938, Jrgen Matthus and Mark Roseman (2010)

- Children during the Holocaust, Patricia Heberer (2011)

- Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume II, 19381940, Alexandra Garbarini with Emil Kerenji, Jan Lambertz, and Avinoam Patt (2011)

- The Diary of Samuel Golfard and the Holocaust in Galicia, Wendy Lower (2011)

- Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume III, 19411942, Jrgen Matthus with Emil Kerenji, Jan Lambertz, and Leah Wolfson (2013)

- The Holocaust in Hungary: Evolution of a Genocide, Zoltn Vgi, Lszl Cssz, and Gbor Kdr (2013)

- War, Pacification, and Mass Murder, 1939: The Einsatzgruppen in Poland, Jrgen Matthus, Jochen Bhler, and Klaus-Michael Mallmann (2014)

- Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume IV, 19421943, Emil Kerenji (2014)

- Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume V, 19441946, Leah Wolfson (2015)

- The Political Diary of Alfred Rosenberg and the Onset of the Holocaust, Jrgen Matthus and Frank Bajohr (2015)

- Nazi Persecution and Postwar Repercussions: The International Tracing Service Archive and Holocaust Research, Suzanne Brown-Fleming (2016)

A project of the

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

SARA J. BLOOMFIELD

Director

Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies

PAUL A. SHAPIRO

Director

JRGEN MATTHUS

Director, Applied Research

under the auspices of the

Academic Committee

of the

United States Holocaust Memorial Council

PETER HAYES, Chair

Doris L. Bergen

Richard Breitman

Christopher R. Browning

David Engel

David Fishman

Zvi Y. Gitelman

Paul Hanebrink

Sara Horowitz

Steven T. Katz

William S. Levine

Deborah E. Lipstadt

Wendy Lower

Michael R. Marrus

John T. Pawlikowski

Alvin H. Rosenfeld

Menachem Z. Rosensaft

George D. Schwab

Michael A. Stein

Jeffrey Veidlinger

James E. Young

This publication has been made possible by support from

The William S. and Ina Levine Foundation

and

The Blum Family Foundation

For USHMM:

Project Manager: Mel Hecker

Translator: Kathleen Luft

Researchers: Holly Robertson Huffnagle, Amanda Pridmore

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Eastover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

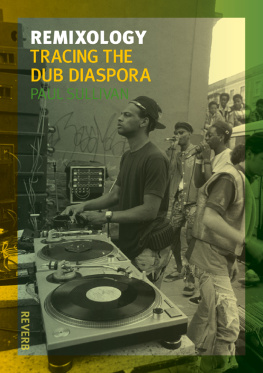

Front cover: USHMMPA WS# 43574

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Brown-Fleming, Suzanne, author.

Nazi persecution and postwar repercussions : the International Tracing Service archive and Holocaust research / Suzanne Brown-Fleming.

Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2016] | Series: Documenting life and destruction: Holocaust sources in context | Includes bibliographical references and index.

LCCN 2015026631| ISBN 9781442251731 (cloth : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781442251755 (e-book)

LCSH: International Tracing Service. | Concentration camp inmatesArchival resourcesGermanyArolsen. | War victimsArchival resourcesConservation and restorationGermanyArolsen. | World War, 19391945Archival resourcesConservation and restorationGermanyArolsen.

LCC HV6762.G3 .B76 2015 | DDC 026/.9405318--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015026631

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

FOREWORD

by Paul A. Shapiro

D URING THE years that I worked to open the archive of the International Tracing Service (ITS)nearly a decade that culminated in the ratification by eleven countries of formal amendments to the international agreements governing the ITSit was difficult to fully comprehend the multiple levels of significance that would emerge once the tens of millions of documents locked up at ITS headquarters in Bad Arolsen, Germany, became fully accessible. Kept out of the reach of survivors, researchers, educators, and others with potential interest, the documents had been utilized for over 60 years almost exclusively for tracing and name search purposes and were being used as the twenty-first century began to validate slave and forced labor compensation claims that flowed in from an already disappearing generation of survivors, who had suffered persecution at the hands of Nazi Germany and her allies. The most common notion regarding ITS was that the archive contained millions of name cards and name lists of various sorts and provenances, and little else. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which administered ITS on behalf of an eleven-country International Commission, made only minimal information available regarding the archives contents and fostered this limited understanding of the archive precisely in order to stifle curiosity and reduce the likelihood that pressure would be brought to bear to open its doors. The ICRC also restricted the information that was available to member states of the International Commission, information that might have motivated Commission members to act sooner than they did, and even recruited well-known specialists, some of whom had enjoyed privileged personal access to the archive, to reinforce the notion that the ITS archives potential for purposes other than tracing and name search would be minimal.

At the time, this mischaracterization of the ITS archive seemed highly credible. It was, after all, difficult to believe that six decades after the end of World War II there remained a place where one could find, hidden from public view, between 50 and 100 million documents relating to the fates of millions of people, Jews and members of virtually every other nationality as well, who were victimized by the Nazis: millions of concentration camp documents; transport and deportation lists; Gestapo arrest warrants; prison records; forced and slave labor documentation that revealed thousands of government, military, corporate, and other users of cheap labor, and the consequences of treating human beings as disposable assets to be used up and discarded; displaced persons (DP) files; and millions of inquiries from around the world from survivors and their families, all hoping at first to find someone still alive, and later simply needing to better understand what had happened to loved ones who had been murdered. And it was difficult for most people to believe that six decades after the end of World War II, the democratic governments on the International Commission, nine from Europe plus the United States and Israel, were responsible for keeping this documentation out of the reach of survivors (and everyone else), and appeared ready, as the twenty-first century began, to see the last remnant of the survivor generation disappear without giving survivors access to records that contained precious information about themselves and their families, and without providing them with the comfort of knowing that the documentary record of what happened to them would not be conveniently kept under wraps, swept under the rug, as one pained Holocaust survivor expressed it to me one day in my office at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), once the survivors were gone.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.