Table of Contents

ALSO BY JOSEPH MAIOLO

Joseph Maiolo, Kirsten Schulze, Jussi Hanhimaki and Antony Best,

An International History of the Twentieth Century

(2nd ed. rev. 2008)

Joseph Maiolo and Robert Boyce, eds.,

The Origins of World War Two:

The Debate Continues (2003)

Joseph Maiolo,

The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany, 1933-1939:

Appeasement and the Origins of

the Second World War in Europe (1998)

To my teacher

Donald Cameron Watt

Cry Havoc, and let slip the dogs of war...

MARK ANTONY,

in Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene 1

Our Legions are brim-full, our cause is ripe.

The enemy increaseth every day;

We, at the height, are ready to decline.

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea we now afloat,

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

MARCUS BRUTUS,

in Julius Caesar, Act IV, Scene 3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks first and foremost to my literary agent, Peter Robinson, without whose constant encouragement and guidance I would not have written this book. At Basic Books I am indebted to Lara Heimert, Norman MacAfee, Robert Kimzey, Kay Mariea, Alex Littlefield and Ross Curley.

I am deeply grateful to Rolf Tamnes, the Director of the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies, who invited me to spend the 2005-6 academic year in Oslo to work on the book, and to the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom, which awarded me a research leave grant in 2008-9 to finish it. I also benefited from the enthusiastic help of three terrific librarians: Irene Kulblik of the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies, Anne C. Kjelling of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, and Geoffrey Bellringer of Kings College London.

Peter Jackson, Antony Best, James Harris, Sven Holtsmark, Massimiliano Fiore, Marcus Faulkner and Steve Casey generously shared their time, expertise and collections of documents with me. John Gooch and Adam Tooze graciously allowed me to read their draft manuscripts. Bob Davies, Robert Self and Evan Mawdsley helpfully answered my questions. I am indebted to Barrie Paskins and Anthony Best for reading the chapters as I wrote them, and to Beatrice Heuser, David Stevenson and Philip Bell for reading the final draft. I am also extremely grateful to Catherine Keen, Mary Keen, Julia Davinskaya, Peter Busch, Alan James, Sam Copeland, Caroline Martin, Stafford Ward, Talbot Imlay, Ksenia Gerasimova, Ksenia Skvortsova, Murielle Cozette, Vivienne Jabri, Helen Fisher, Richard Mason, David Wardle, Martin Collins, Douglas Matthews, Ian Paten, Bernard Dive, Caroline Westmore, Jeffrey Ward, Therese Klingstedt and Alessio Patalano. Last but not least I am grateful to my students over the years at Kings College London for sharpening my ideas.

Finally a note on the text. For the sake of readability I have generally avoided using foreign terms. For Japanese and Chinese names, I have followed the practice of those cultures and placed the family name first. I have not distinguished between grades of senior military ranks: thus, rear admirals and brigadier generals are simply admirals and generals. Fascism refers to the Italian political movement, and fascism for the political phenomenon in general. To devote my time and energy to less accessible sources, where an adequate translation of a source was available (Cianos diary, for instance), I have quoted from it.

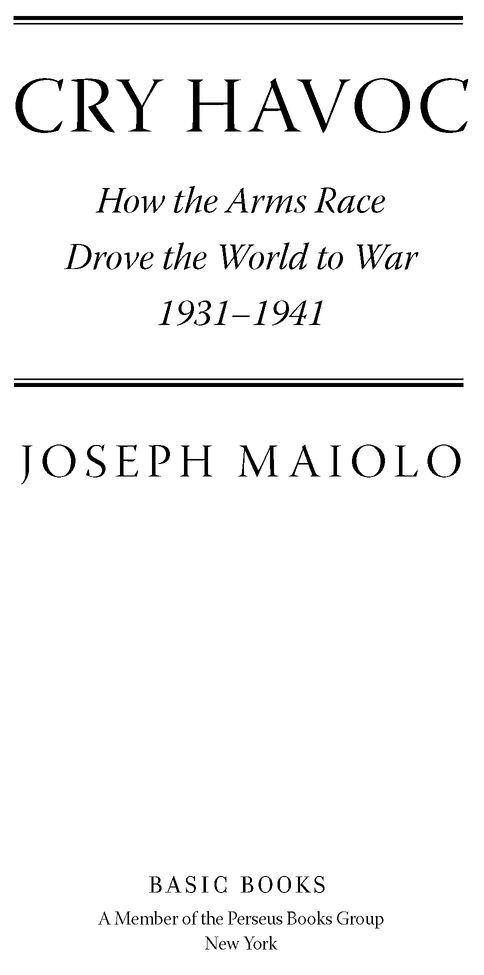

THE GREAT POWERS, 1936

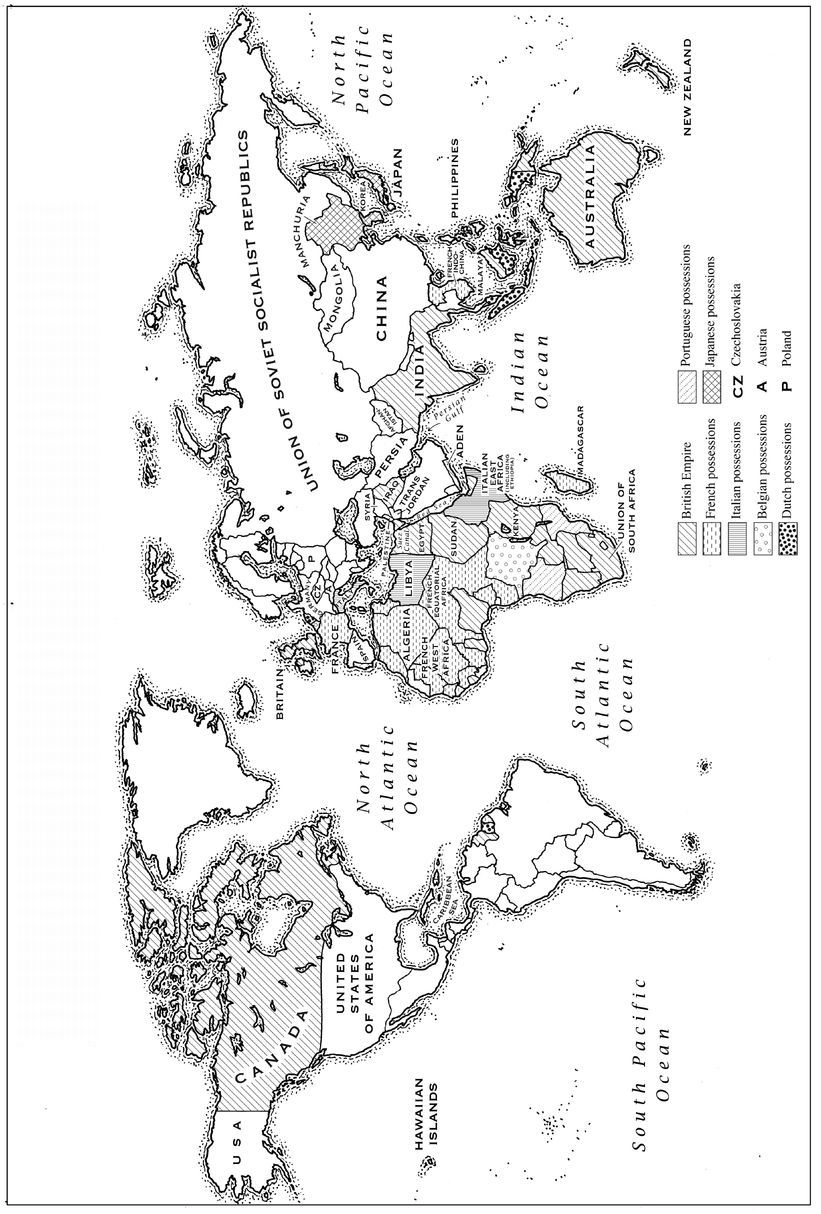

CENTRAL EUROPE, 1933-1939

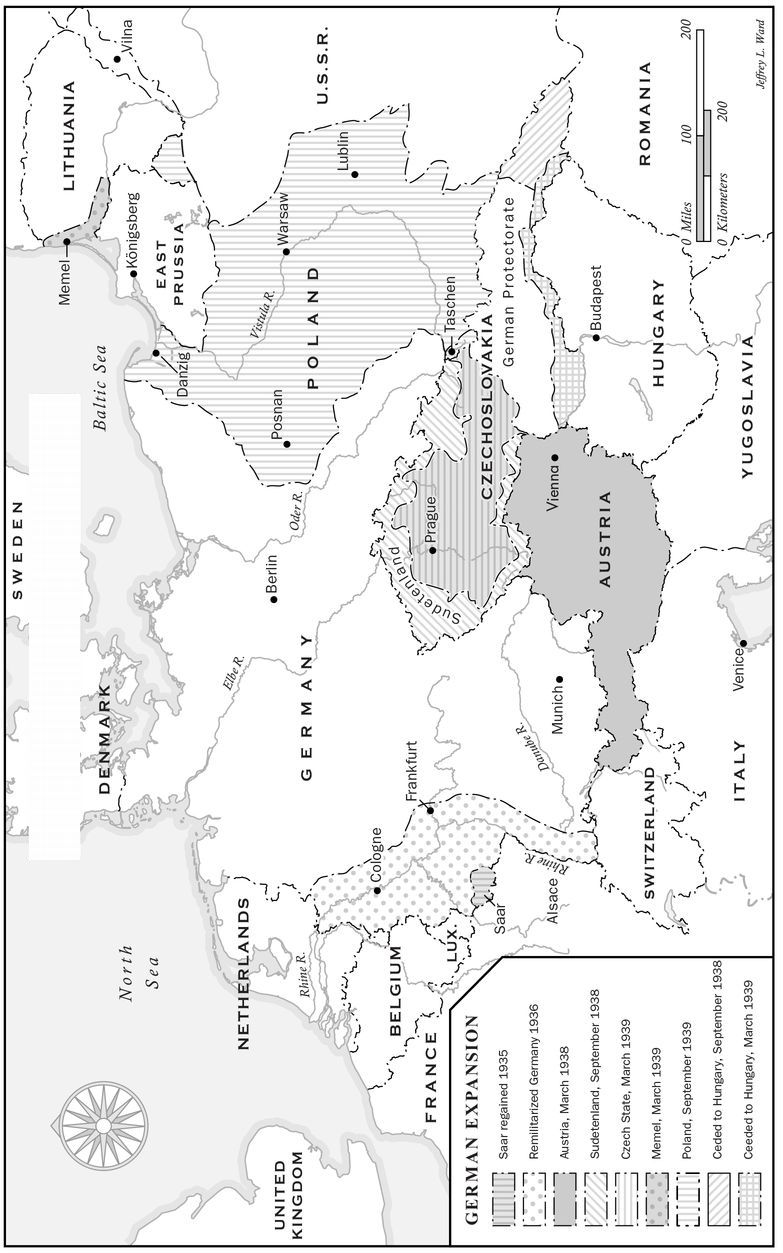

SOVIET-JAPANESE FRONTIER CLASHES IN THE 1930S

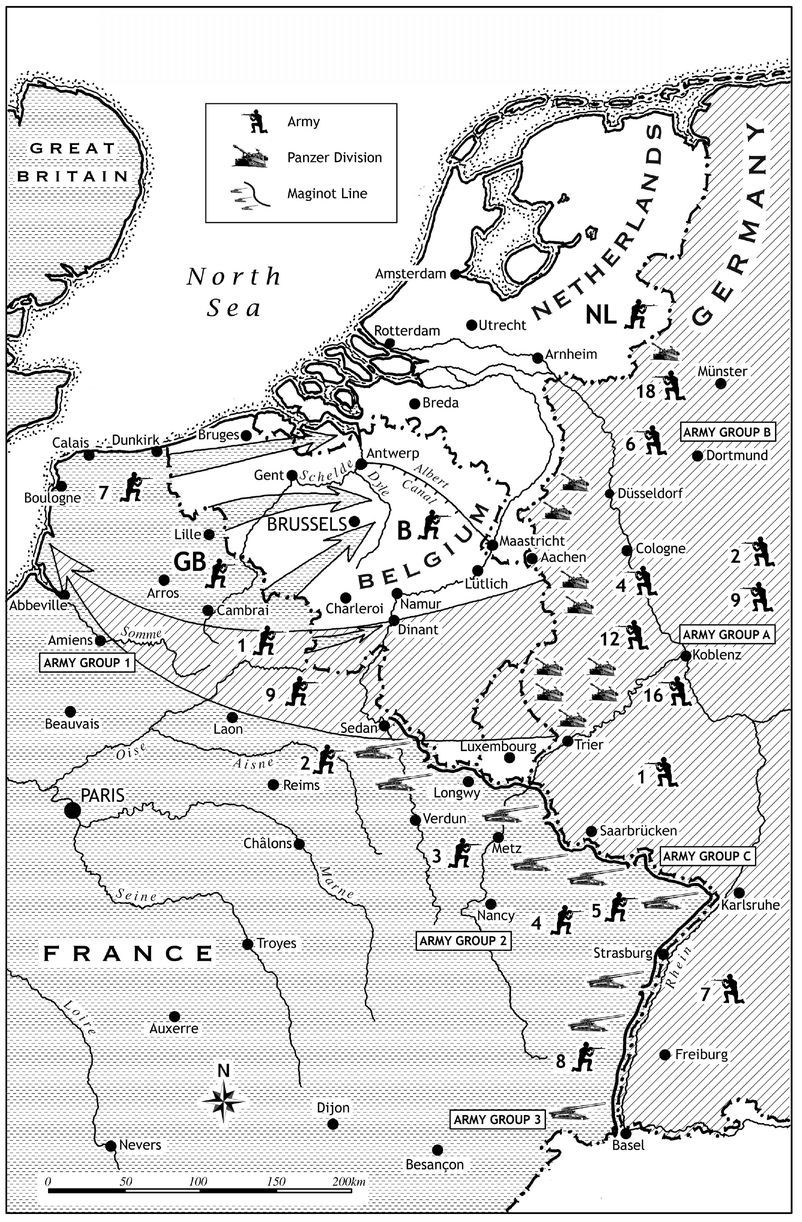

THE GERMAN AND ALLIED OPERATIONAL PLANS, MAY 1940

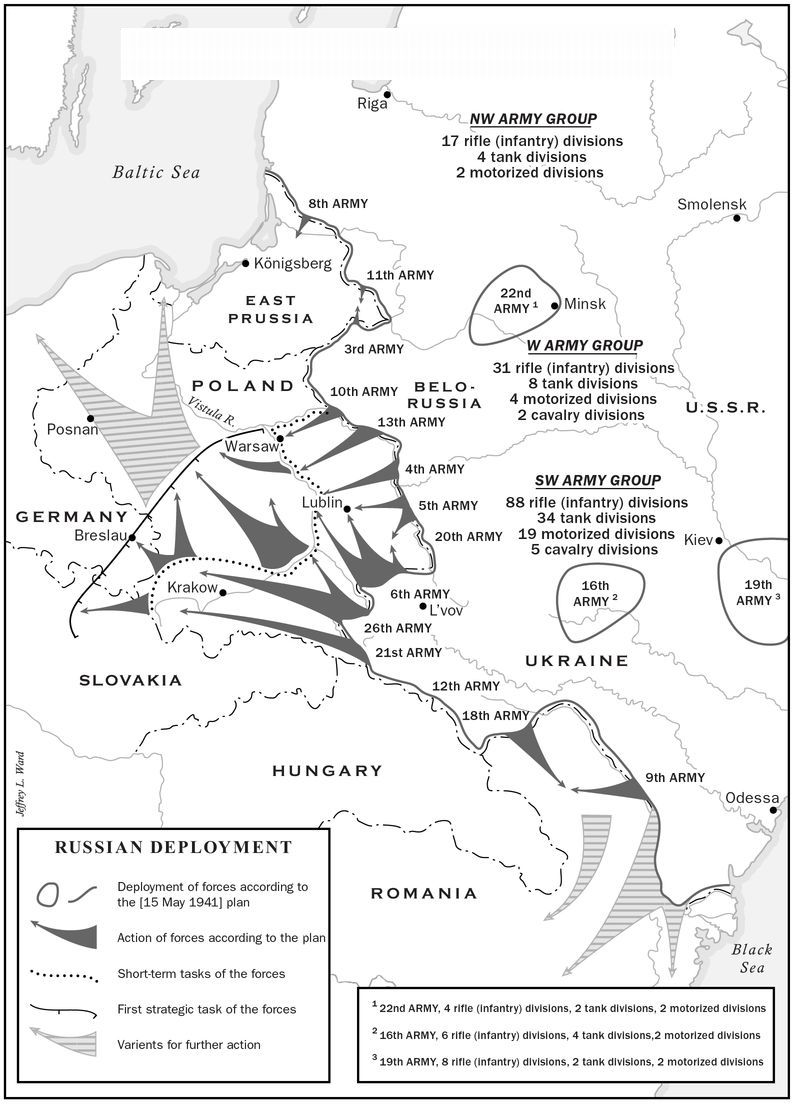

ZHUKOVS 15 MAY 1941 WAR PLAN

INTRODUCTION

In the summer of 1914, the major European powers plunged into war with offensive plans for quick victories. By the winter those plans had come to naught. The elusive short war of maneuver turned into a long one of trenches and grinding industrial attrition. During 1915, Europes political leaders and general staffs soon discovered that they lacked the deep reserves of men and munitions to wage what would be called total war.

As the battles raged on, governments scrambled to turn whole economies and societies into gigantic war machines. Raising the vast quantities of men, money and munitions demanded industrial and popular regimentation on an unprecedented scale. Peacetime government structures creaked and groaned under the mounting pressure. Existing bureaucracies swelled, and new hydra-like mobilization agencies sprang up as powerful emergency instruments of state control and central planning. While wartime leaders diverted ever larger percentages of national resources into producing war materiel, prewar patterns of trade and financial practices became distorted and market forces were curbed. Those who lived through the war experienced it as a titanic siege fought between economies and societies racing toward all-out mobilization.

Naturally, the cataclysm made an indelible imprint on the minds of those who survived it and who came of age after it. For many officials, soldiers, statesmen, scholars and industrialists of all political shades, the war had opened up the awe-inspiring possibility that in the future technocratic elites could rationally plan and manage entire industrial economies and societies to realize grand political aspirations. In the years just after the conflict, however, the overwhelming political impulse among the victors was not to perfect the wartime practices of centralized state control but to put into reverse the political, economic and social distortions generated by total war.

During the 1920s one of the major feats of this demobilization project was the restoration of the pre-1914 mechanism of international currency stabilization and exchange known as the gold standard. By adhering to the gold standard, all the capitalist states not only promoted the smooth flow of trade and capital across frontiers but also locked themselves into a strict budgetary discipline that would inhibit massive arms build-ups. Among the major capitalist nations, the onset of the Great Depression from 1929 onward broke the trend toward demobilization. The industrial slump, the spectacular failure of markets to self-correct and the breakdown of the gold-standard system helped to propel into positions of power many cohorts of eager scholars, bureaucrats, soldiers and politicians who dreamed of salvation through the exercise of advocated state control over aspects of national life, especially markets.