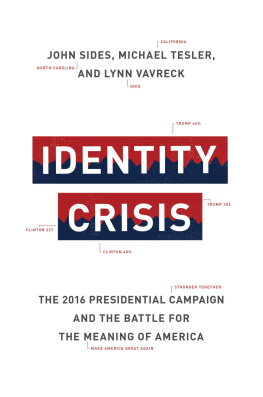

John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck

IDENTITY CRISIS

The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018947736

ISBN 978-0-691-17419-8

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Jacket design by Faceout Studio, Lindy Martin

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Ideal Sans

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

To Henry Brady, Jack Citrin, Dick Fenno, and David Sears:

Without them, there is no us.

CONTENTS

FIGURES AND TABLES

CHAPTER 1

Fayetteville

Rakeem Jones didnt see the punch coming.

He had been part of a group protesting at a rally for presidential candidate Donald Trump in Fayetteville, North Carolina. It was March 9, 2016, and Trump was leading the race for the Republican presidential nomination. After Trump began speaking, one of the group started shouting at Trump. A Trump supporter screamed at the group, You need to get the fuck out of here! The group was soon surrounded by sheriffs deputies, who began to escort them out. Jones gave the audience the finger. Another member of the group, Ronnie Rouse, said that someone shouted, Go home, niggers! (Both Rouse and Jones are black.)

As police led Jones out, seventy-eight-year-old John McGraw, who uses the nickname Quick Draw McGraw, moved to the end of his row and sucker-punched Jones as he walked past. Jones was then tackled by the deputies, who said they had not seen McGraws punch. McGraw, who is white, was able to leave the event and was interviewed afterward by a reporter from the program Inside Edition . When asked if he liked the rally, he said, You bet I liked it. When asked what he liked, McGraw said, Knocking the hell out of that big mouth. Then he said, We dont know who he is, but we know hes not acting like an American. The next time we see him, we might have to kill him. The day after, McGraw was identified, arrested, and charged with assault and battery and disorderly conduct.

The incident went viral. One reason was Rouses cell phone footage of the attack. Another was Trumps reaction. In his speech in Fayetteville, Trump

The attack on Rakeem Jones was just one of several violent incidents involving protesters and attendees at Trump rallies. Two days after the Fayetteville rally, the Trump campaign canceled a rally planned for the University of Illinois at Chicago when violence erupted between Trump supporters and protesters. And Trumps reaction to the attack on Jones was just one of many times when he condoned violence against protesters. After a Black Lives Matter activist was attacked and called nigger at a November 2015 rally in Birmingham, Trump said, Maybe he should have been roughed up because it was absolutely disgusting what he was doing. On other occasions, referring to protesters, he said, Knock the crap out of them and Id like to punch him in the face and Ill beat the crap out of you.

What happened in Fayetteville, Birmingham, and other places revealed something else about the election. McGraws comment We know hes not acting like an American distills what the election was fundamentally about: a debate about not only what would, as Trump put it, make America great again, but who is Americaand Americanin the first place. It was a debate about whether the president himself, Barack Obama, was an American. It was a debate about how many immigrants to admit to the country. It was a debate about how much of a threat was posed by Muslims living in or traveling to the United States. It was a debate about whether innocent blacks were being systematically victimized by police forces. It was a debate about whether white Americans were being unfairly left behind in an increasingly diverse country.

What these issues shared was the centrality of identity . How people felt about these issues depended on which groups they identified with and how they felt about other groups. Of course, group identities have mattered in previous elections, much as they have in American politics overall. But the question is always which identities come to the fore. In 2016, the important groups were defined by the characteristics that have long divided Americans: race, ethnicity, religion, gender, nationality, and, ultimately, partisanship.

What made this election distinctive was how much those identities mattered to voters. During Trumps unexpected rise to the nomination, support for Trump or one of his many rivals was strongly linked to how Republican voters felt about blacks, immigrants, and Muslims, and to how much discrimination Republican voters believed that whites themselves faced. This had not been true in the 2008 or 2012 Republican primaries. These same factors helped voters choose between Trump or Hillary Clinton in the general electionand, again, these factors mattered even more in 2016 than they had in recent presidential elections. More strikingly still, group identities came to matter even on issues that did not have to be about identity, such as the simple question of whether one was doing okay economically.

In short, these identities became the lens through which so much of the campaign was refracted. This book is the story of how that happened and what it means for the future of a nation whose own identity is fundamentally in question.

The Political Power of Identity

That identity matters in politics is a truism. Getting beyond truisms means answering more important questions: which identities, what they mean, and when and how they become politically relevant. The answers to these questions point to the features of the 2016 election that made group identities so potent.

People can be categorized in many groups based on their place of birth, place of residence, ethnicity, religion, gender, occupation, and so on. But simply being a member of a group is not the same thing as identifying or sympathizing with that group. The key is whether people feel a psychological attachment to a group. That attachment binds individuals to the group and helps it develop cohesion and shared values.

The existence, content, and power of group identitiesincluding their relevance to politicsdepends on context. One part of the context is the possibility of gains and losses for the group. Gains and losses can be tangible, such as money or territory, or they can be symbolic, such as psychological status. Moreover, gains and losses do not even need to be realized. Mere threats, such as the possibility of losses, can be enough. When gains, losses, or threats become salient, group identities develop and strengthen. Groups become more unified and more likely to develop goals and grievances, which are the components of a politicized group consciousness.

Another and arguably even more important element of the context is political actors. They help articulate the content of a group identity, or what it means to be part of a group. Political actors also identify, and sometimes exaggerate or even invent, threats to a group. Political actors can then make group identities and attitudes more salient and elevate them as criteria for decision-making.

A Changing America

The social science of group identity points directly to why these identities mattered in 2016. First, the context of the election was conducive. The demographics of the United States were changing. The dominant majority of the twentieth centurywhite Christianswas shrinking. The country was becoming more ethnically diverse and less religious. Although the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, no longer dominated the nations consciousness, there were other terrorist attacks in the United States and elsewhere. The civil rights of African Americans were newly salient, as the Black Lives Matter movement coalesced to protest the deaths of unarmed blacks at the hands of police. Indeed, several high-profile incidents between the police and communities of color made Americans more pessimistic about race relations than they had been in decades. Moreover, there was no recession or major war, either of which tends to dominate an election-year landscape, as the Great Recession and financial crisis did in 2008 and the Iraq War did in 2004. This created more room for different issues to matter.

Next page