Contents

DEFIANT BRACEROS

THE DAVID J. WEBER SERIES IN THE NEW BORDERLANDS HISTORY

Andrew R. Graybill and Benjamin H. Johnson, editors

Editorial Board

Juliana Barr

Sarah Carter

Kelly Lytle Hernandez

Cynthia Radding

Samuel Truett

The study of borderlandsplaces where different peoples meet and no one polity reigns supremeis undergoing a renaissance. The David J. Weber Series in the New Borderlands History publishes works from both established and emerging scholars that examine borderlands from the precontact era to the present. The series explores contested boundaries and the intercultural dynamics surrounding them and includes projects covering a wide range of time and space within North America and beyond, including both Atlantic and Pacific worlds.

Published with support provided by the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed and set in Miller and Caecilia by Rebecca Evans

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

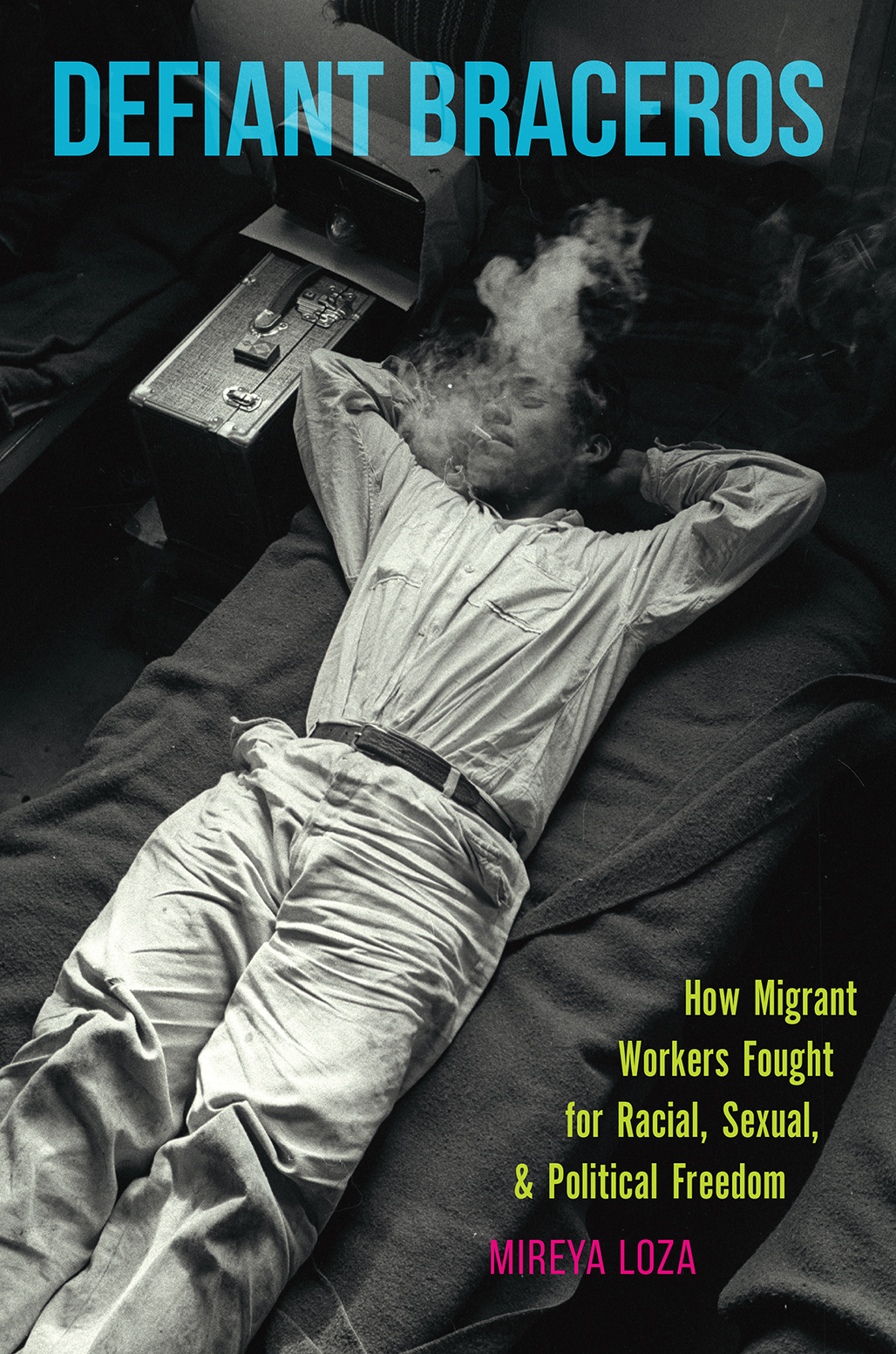

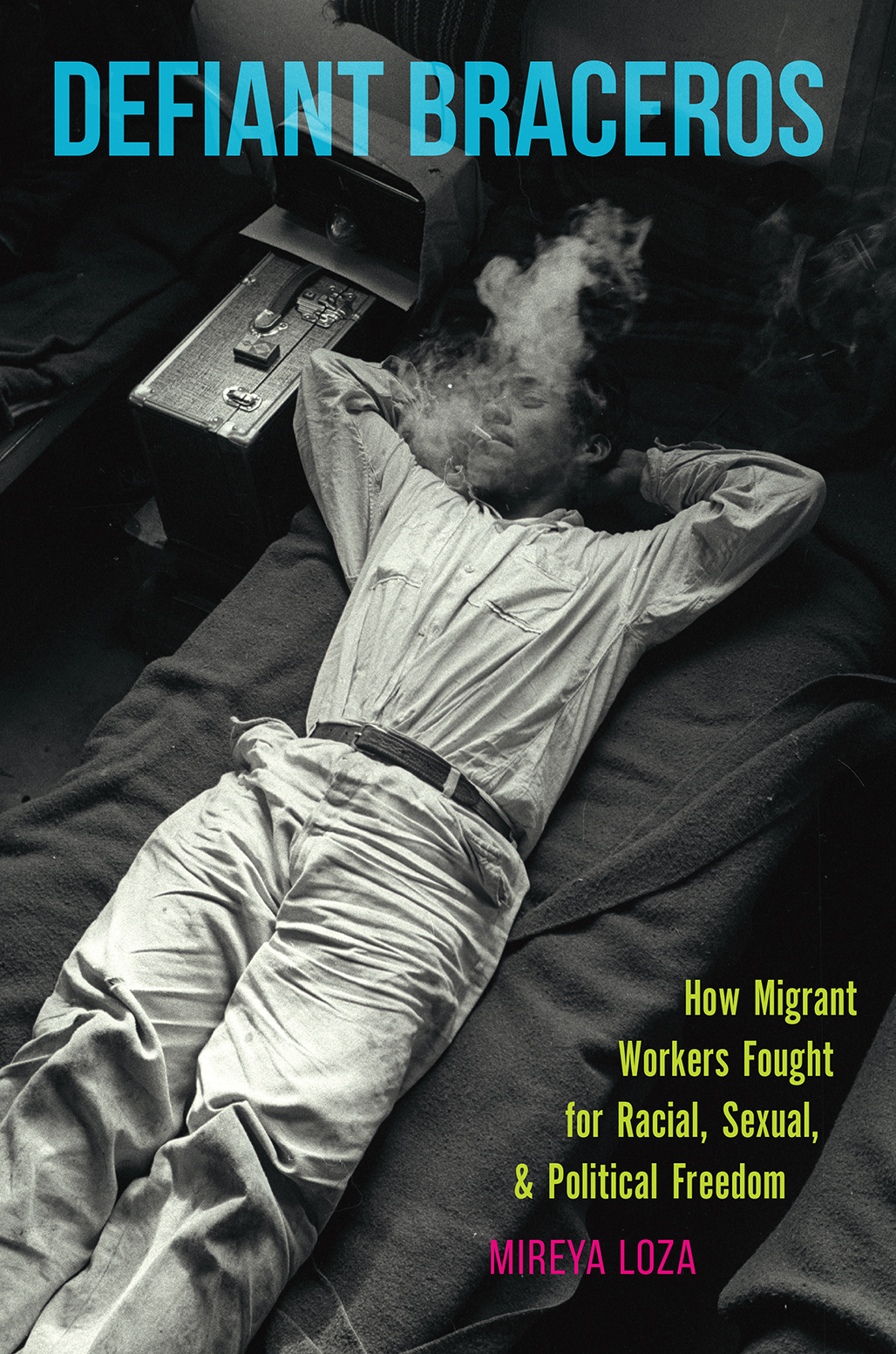

Cover illustration: Leonard Nadel, A Bracero Lies in Bed and Smokes in a Living Quarter at a Californian Camp. Item #2470, Leonard Nadel Bracero Photographs, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Loza, Mireya, author.

Title: Defiant braceros : how migrant workers fought for racial, sexual, and political freedom / Mireya Loza.

Other titles: David J. Weber series in the new borderlands history.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2016] |

Series: The David J. Weber series in the new borderlands history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016009978 | ISBN 9781469629759 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469629766 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469629773 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Foreign workers, MexicanUnited StatesHistory. | MexicansRace identityUnited States. | Foreign workers, MexicanPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory. | Foreign workers, MexicanUnited StatesSocial conditionsHistory. | Foreign workers, MexicanUnited StatesEconomic conditionsHistory. | Seasonal Farm Laborers Program.

Classification: LCC HD 8081. M 6 L 67 2016 | DDC 331.5/440973dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016009978

Sections of chapter 3 previously appeared as Alianza de Braceros Nacionales de Mexico en los Estados Unidos, 19431964, in Que Fronteras? Mexican Braceros and a Re-examination of the Legacy of Migration, ed. Paul Lopez (Dubuque: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2010), and will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal Diagolo.

For Marcelina, Pedro, Rosalba, and Juan Loza

Contents

Making Braceros

Race, Modernity, and the Transformational Politics of Transnational Labor

Intimate Economies in the Bracero Program

Alianza de Braceros Nacionales de Mxico en los Estados Unidos

Creating the Bracero Justice Movement

Representing Memory: Braceros in the Archive and Museum

Illustrations

1 Hoy, June 16, 1951

2 Salto Mortal, by Arias Bernal, Siempre! Presencia de Mexico, January 23, 1954

3 Boots and Sandals in Agricultural Life

4 Isaias Snchezs identification as an experienced date worker

5 Julio Valentn May-Mays bracero identification, front side, June 19, 1962

6 La Union Es Nuestra Fuerza

7 Miguel Estrada Ortizs Alliance of National Workers of Mexico in the United States of America identification, June 21, 1960

8 Ventura Gutirrez holding a microphone protesting with ex-braceros, Mexico City, April 7, 2003

9 Medical examinations circa 1943, originally published in Snapshots in a Farm Labor Tradition, by Howard R. Rosenberg, Labor Management Decisions 3, no. 1 (1993)

10 Manuel de Jess Roman Gaxiolas Alianza Bracero Proa identification card

11 Leonard Nadel, Braceros Playing Cards

12 Leonard Nadel, Short Handle Hoe

13 Bittersweet Harvest exhibition entry

14 Bittersweet Harvest exhibition exit

Acknowledgments

This book was written with the support of many communities. As an undergraduate, I was fortunate enough to take a class with someone who would change the course of my life. Matt Garcia introduced me to bracero history in an academic setting, and I owe him a debt of gratitude for all of the time and energy he spent preparing me to write this book. Vicki Ruizs generous guidance broadened my scholarship. Kristin Hoganson and Adrian Burgos provided thoughtful edits, feedback, and, most of all, unwavering mentorship. Natalia Molina, Jason Ruiz, Jos Alamillo, and Anitra Grisales engaged in my ideas and helped map out new terrains. Stephen Pitti and George Sanchez graciously transformed this project. Near and dear to my heart is my University of Texas community: Gilberto Rosas, Korinta Maldonado, Isabella Seong Leong Quintana, Pablo Gonzlez, Nancy Rios, Fernanda Soto, Jamahn Lee, Jennifer Njera, and Peggy Brunache. At Brown University, I was also fortunate to receive amazing guidance from Evelyn Hu-Dehart, Ralph Rodriguez, Steven Lubar, Elliot Gorn, and Susan Smulyan. Felicia Salinas, Marcia Chatelain, Matt Delmont, Jessica Johnson, Monica Martinez, Monica Pelayo, and Eric Larson made my time on the East Coast memorable. Sarah Wald was a great virtual writing partner, checking in and keeping me focused. My colleagues at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign created an environment of open support: Ricky Rodriguez, Fiona Ngo, Lisa Cacho, David Coyoca, Isabel Molina, Soo Ah Kwon, Jonathan Inda, Julie Dowling, Alejandro Lugo, Edna Viruell-Fuentes, and Sandra Ruiz. Andrew Eisen and Veronica Mendez worked hard to digitize documents, track down footnotes, and secure copyrights. University of Illinois graduate students Raquel Escobar, Carolina Ortega, and Juan Mora and undergraduate Emmanuel Salazar kept me on my toes. Many others helped me with advice and support: Bill Johnson-Gonzlez, Simeon Man, Julie Weise, Geraldo Cadava, Kathleen Belew, Michael Innis-Jimnez, Lori A. Flores, and Perla Guerrero. This project was funded by the University of Illinois, the Ford Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Formby Research Fellowship at Texas Tech University, Historical Society of Southern California, Smithsonian Institution, the Mexico-North Research Network, and Brown University.

None of this would be possible without the Bracero History Project and the collective effort it took to get it up and running, from folks at George Mason Universitys Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and the University of Texas at El Pasos Institute of Oral History to Brown Universitys Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. Amazing people came together to document extraordinary experiences, and I was fortunate enough to work alongside Kristine Navarro, Steve Velasquez, Peter Liebhold, Anais Acosta, Sharon Leon, and Alma Carrillo. Their commitment to public history continues to inspire me. I am also indebted to every person who collaborated with the project and recognized that these oral histories are important. I also want to thank every community member, undergraduate student, and graduate student who was committed to this endeavor and pressed the record button, asked great questions, and captured these oral histories. Most of all, the Bracero History Project thrived because of individuals who shared their stories and went on record to make sure this history was remembered.