A VERY CAPITALIST CONDITION

A History and Politics of Disability

Roddy Slorach

Roddy Slorach is a longstanding socialist based in east London who works as a disability adviser in Higher Education.

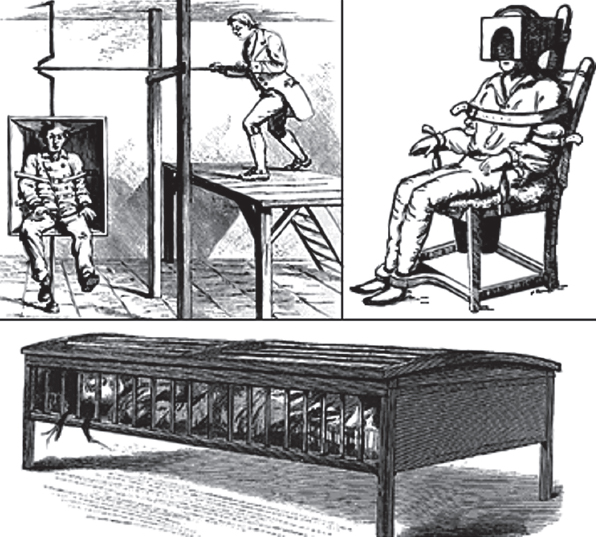

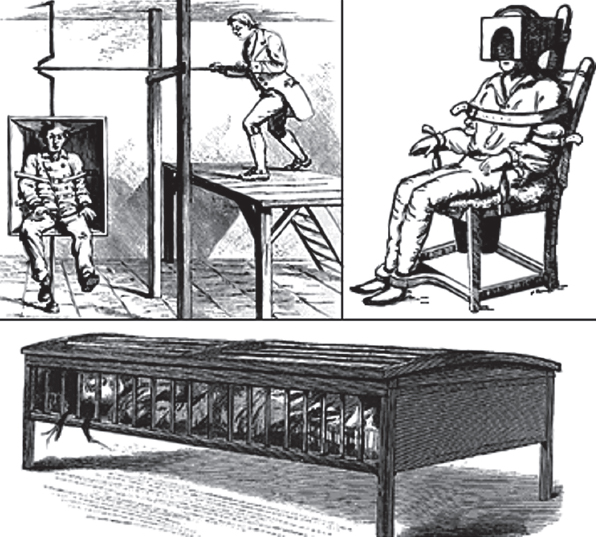

Treatment for mental distress: crude devices used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did not offer any real relief. Depressed patients were spun at high speeds in the circulating swing (top left). The Tranquilizing Chair (top right)was invented in 1769 as treatment for mania, by US doctor Benjamin Rush, considered the father of modern psychiatry. The crib (bottom) was widely used to restrain violent patients. (Image from http://bipolarworld.net/Bipolar20%Disorder/History/hist12.htm)

Shell-shocked British soldier in the trenches of the First World War.

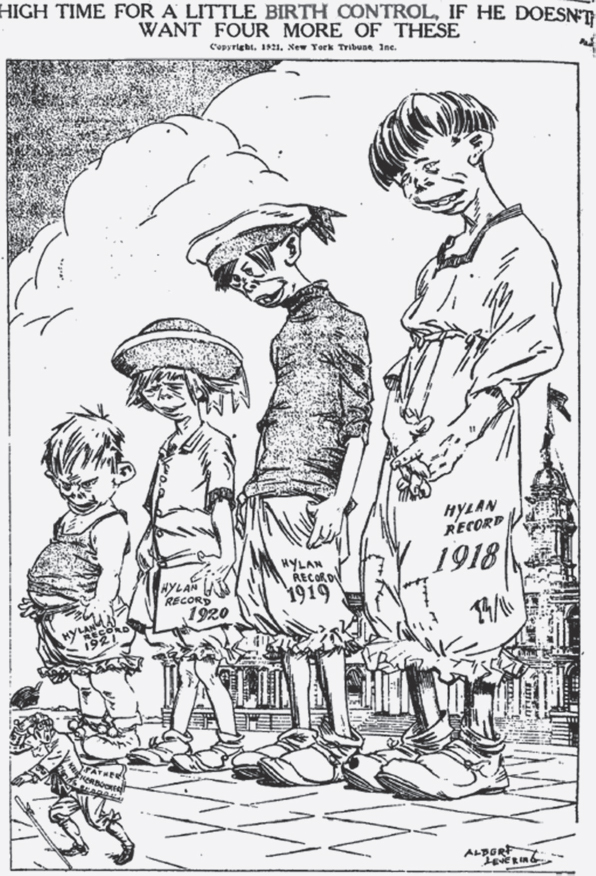

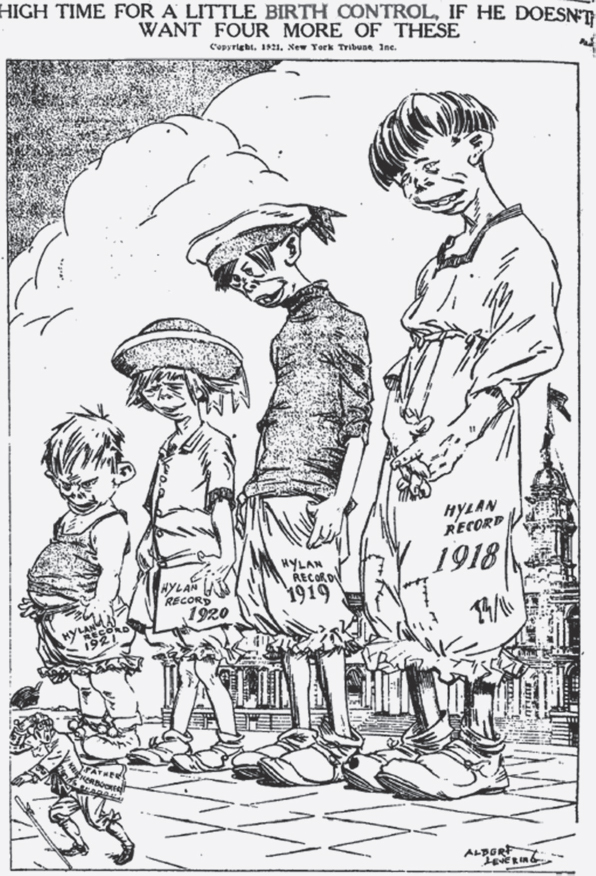

Eugenics was mainstream in US culture: cartoon from New York Tribune, 10 November 1921.

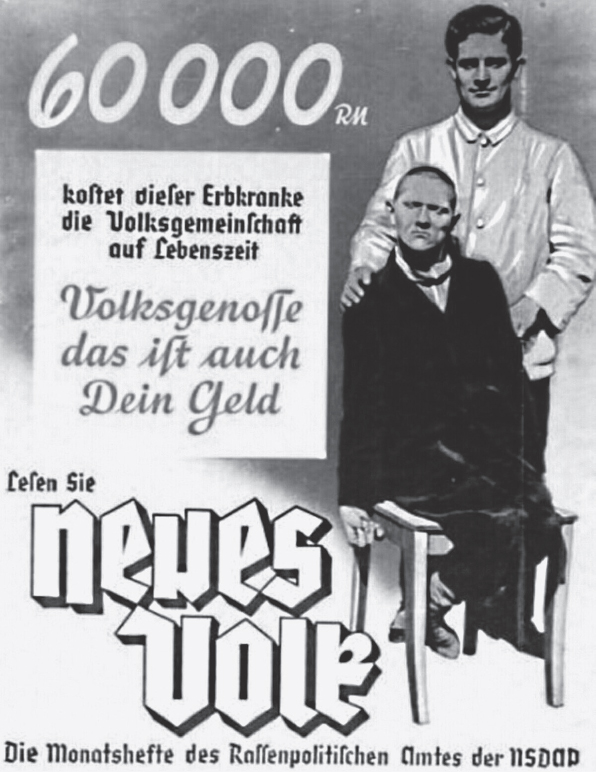

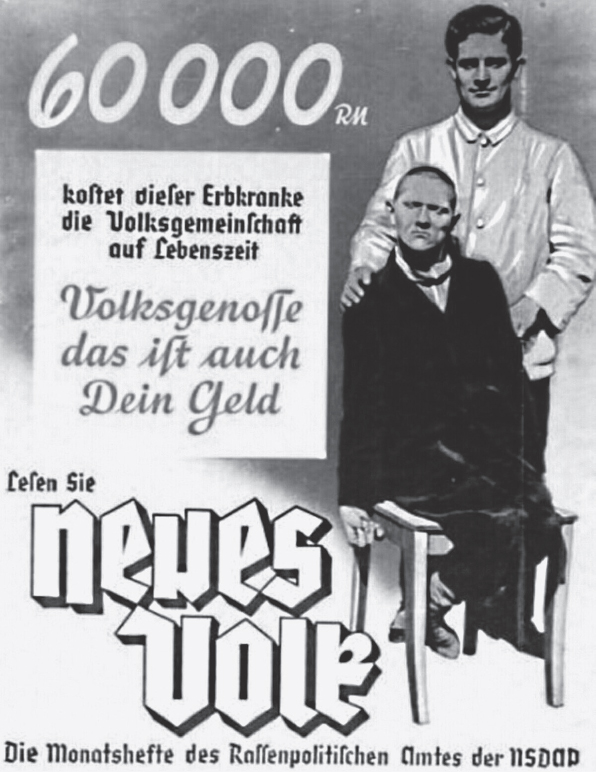

Nazi eugenics propaganda poster. Text reads: This person suffering from hereditary defects costs the community 60,000 Reichsmarks during his lifetime. Fellow German that is your money too.

Hitler greets disabled veterans, Berlin, March 1939.

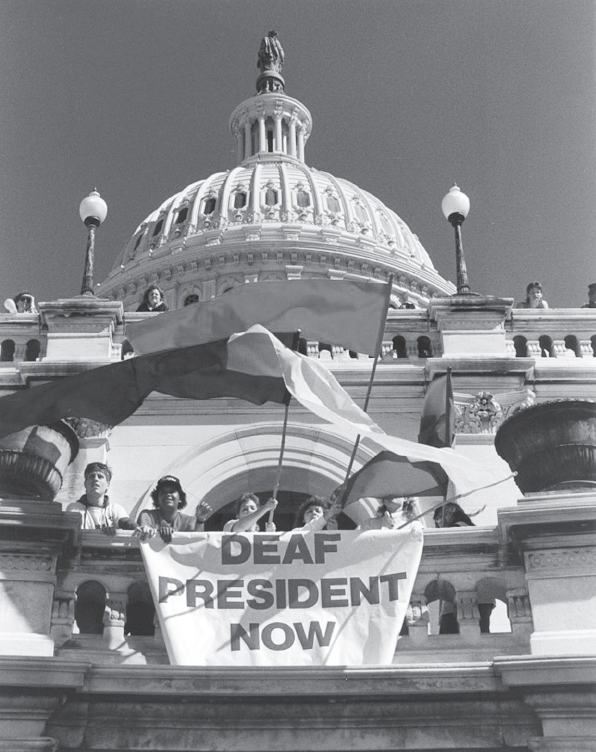

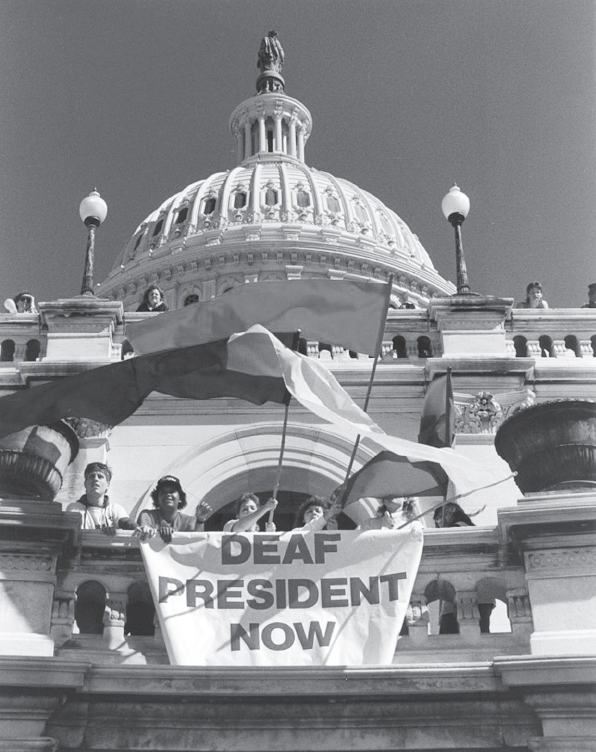

Deaf students at the Capitol building during their occupation at Gallaudet University, Washington DC, March 1988.

A VERY CAPITALIST

CONDITION

A History and Politics

of Disability

Roddy Slorach

A Very Capitalist Condition: A History and Politics of Disability

By Roddy Slorach

Published 2016 by Bookmarks Publications

c/o 1 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3QE

Bookmarks Publications

Typeset by Peter Robinson

Cover by Esther Neslen

Printed by The Russell Press

ISBN 978 1 910885 01 7 (pbk)

978 1 910885 02 4 (Kindle)

978 1 910885 03 1 (ePub)

978 1 910885 04 8 (PDF)

Contents

Acknowledgements

I owe a debt to many people for their help in writing this book. It would certainly not have been possible without Mike Oliver and Vic Finkelstein, whose development of the social model comprised the first Marxist understanding of disability. Any criticisms I have of their work has benefited from the several decades of wide-ranging debate it inspired.

Some research was particularly helpful in turning a vague idea into a clearer plan, particularly Martha Roses book on ancient Greece and Irina Metzlers work on feudalism. Chris Stringer suggested key sources on the earliest human societies. Thanks to Martin Empson for comments on an early draft of .

More generally, several sections of the book benefited from discussion with Nicki Martin, Rob Murthwaite and Ellen Clifford. I owe greatest thanks to Lee Humber, who gave me sound advice on the books content and structure, and to Sheila McGregor and Gareth Jenkins, who both provided invaluable comments on an advanced draft. Thanks too to Esther Neslen for the great cover design, and to Peter Robinson, Carol Williams, Eileen Short and Lina Nicolli for their work on the production.

Last but certainly not least, thanks to Daniela for all her patience and support.

Responsibility for the final text, including any mistakes or wrong judgments or arguments, is of course mine alone, particularly as I did not always follow the advice offered.

I dedicate this book to my mother.

1.

Introduction

Disability in contemporary society is a complex and widely misunderstood issue. Two contradictory trends in recent years illustrate this well.

The first global report on disability, published by the World Health Organisation in 2011, identified 1 billion disabled people 15 percent of the global population. As a proportion of the total, this figure is expected to continue rising for the foreseeable future. Since its adoption in December 2006, over 150 countries have ratified the United Nations (UN) Convention on Rights for People with Disabilities. Thanks largely to pressure from the worlds most influential disability movements, Britain and the US adopted antidiscrimination laws championed by the UN as models of best practice. Many other states have adopted similar legislation, with others likely to follow in the near future. As an international political issue, the profile of disability rights has in many respects never been higher.

Another side to disability, however, is better known to many more people. Today, the media and governments in Britain and the US routinely allege fraud by benefit scroungers or fakers to justify drastic cuts in disability-related benefits and services. In a climate of escalating austerity and protracted economic crisis, this pattern is increasingly being emulated elsewhere. In Britain, definitions have been altered to reduce the number of those deemed to be genuinely disabled, and therefore (supposedly) deserving of support. The drastic nature of these welfare reforms is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that, in the summer of 2015, disabled activists succeeded in persuading the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to investigate alleged violations of disabled peoples human rights in the UK; the findings of the confidential investigation are due to be published in 2017. Another aspect of this more negative side to disability is the remarkable fact that the vast majority of those still officially classified as disabled neither disclose this to employers nor identify as such to anyone else.

What explains these contradictory trends? What, indeed, is disability in the first place? This book sets out to answer these questions by examining the social and historical roots of the nature of disability discrimination.

Disability was first identified as a particular form of discrimination at the end of the 19th century. The modern disability movement, however, only emerged in the decades after the Second World War. Referred to by one author as the last civil rights movement, disability activism only began to peak after others, such as those of women, black people and gays and lesbians had already passed into decline. In Britain the disability movement has recently revived after an absence of almost 20 years in response to government cuts in disability-related benefits and services.

Most writing about disability falls into one of three categories. First, there are personal stories, mainly of overcoming adversity or the tragedy of living with impairment. Although tending to reinforce stereotypical notions of heroic superhumans, these may often provide important insights into the lives of individual disabled people. Second, there are accounts by and for health care or social service professionals. Finally, most discussion in the academic discipline of Disability Studies takes place in expensive specialist journals, the language of which is often impenetrable and the content of questionable relevance. The aim of this book is to build on the scattered handful of historical accounts of disability and disabled people, to provide a wider history that is also accessible to a broader audience.

Next page