Billaud - Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence)

Here you can read online Billaud - Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc., genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Billaud: author's other books

Who wrote Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence)? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Kabul Carnival

THE ETHNOGRAPHY OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE

Tobias Kelly, Series Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

KABUL CARNIVAL

Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan

Julie Billaud

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2015 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Billaud, Julie, author.

Kabul carnival : gender politics in postwar Afghanistan / Julie Billaud.

pages cm (The ethnography of political violence)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4696-4 (alk. paper)

1. WomenAfghanistanSocial conditionsHistory21st century. 2. Nationalism and feminismReligious aspectsIslamHistory21st century. 3. Postwar reconstructionAfghanistan. 4. Public spacesAfghanistanHistory21st century. 5. Violence against womenAfghanistanHistory21st century. I. Title. II. Series: Ethnography of political violence.

HQ1735.6.B55 2015

305.409581dc23

2014040354

Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the worlds revival and renewal, in which all take part. Such is the essence of carnival, vividly felt by all its participants.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

If Only You Were Born a Boy

As I grew up, my mother constantly repeated to me: if only you were born a boy. So I eventually became one. This is the pragmatic way in which eighteen-year-old Zahra explains how she became Zia. Zahra rents a small room in a family house located next to Kabul Polytechnic University. When, a couple of years ago, her parents divorced and remarried, none of them wanted her around anymore. Mistreated by her stepfather, neglected by her mother, and with no relatives to take care of her, she set out to take her future into her own hands and not to rely on anyone. Because of the fact that as a girl she could not enjoy this level of autonomy, she cut her hair short, purchased boys clothes, changed her gender identity, and found herself a job in a small cultural organization. With her big hazel eyes, her confident appearance, and her direct way of staring at people, Zahrawho becomes Zia as soon as she steps outside the houseeasily passes herself off as a handsome young man.

I met Zahra through my friend Fawzia who boards at the National Womens Dormitory. Fawzia befriended Zahra at the self-defense class they both attend once a week at Bagh-e Zanana, the womens park. The walls of Zahras bedroom are covered with posters of Jackie Chan and Bollywood movie stars. As she casually lights up a cigarette, tipping her head back to blow away large clouds of blue smoke, she comments: Now, I can do whatever I want. I can ride a bike, do the shopping, go to work. I can even be mahram [an unmanageable kinsman; a woman must be accompanied by such an escort outside her house] for my girlfriends! I will never go back!

You see, Julie, she is a bacha posh [girl dressed like a boy]! She even thinks like a boy! Deep inside, she is a boy and a beautiful one! says Fawzia, and then she leans forward to whisper in my ear: I love Zahra! Zahra is my boyfriend! and she bursts into laughter.

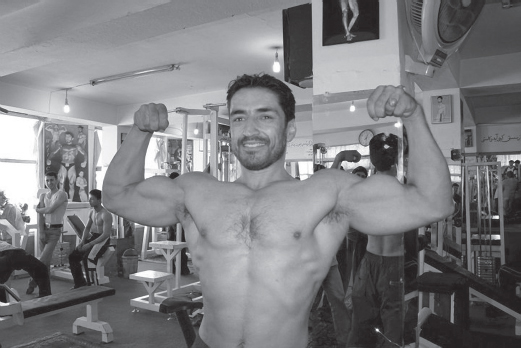

Figure 1. Man showing his muscles in a body-building club in Kabul. Photo by Mlanie De Segundo.

Before I met Zahra, Fawzia had told me about her new friendship with great excitement, recounting in a highly colorful manner how Zahra sometimes engaged in fights with boys and the respect with which her colleagues at work treated her. Since they had met, Fawzia and Zahra had started to call and send text messages to each other several times a day, exchanging sweet words and pieces of poetry like lovers sometimes do. On that day, Fawzia had brought Zahra a nazarband (lucky charm), a necklace meant to protect her against cheshme bad (the evil eye).

Zahra immediately captured my attention. I wondered if bacha posh in Afghanistan enjoyed some kind of social recognition as do the third gender hijras of India and Pakistan. It was apparently not the case and Zahra took great risks masquerading as a boy in the streets of Kabul. If she was discovered she could be beaten up or even arrested by the police. Raised as a girl, she had had to train herself hard to adopt the manners of a boy. Now, I cannot be shy anymore! I have to be tough, tough like a boy! she said, rolling up her sleeves to show me her muscular but rather thin arm. I am lucky, I dont have much here, she said pointing at her flat breasts.

When I asked friends around me if they knew some bacha posh , I was surprised to discover that many of them knew families who had turned one of their daughters into a boy. The cross-dressing of little girls is an option sometimes chosen by parents to cope with the social pressure to have a boy and the economic need to have a child able to work outside of the house. Parents who fail to produce a son sometimes decide to make one up, usually by cutting the hair of a daughter and dressing her in typical Afghan mens clothing. There is no law, religious or otherwise, prohibiting the practice even though it remains a taboo and families tend to keep their secret well hidden. In most cases, young women return to womanhood once they reach puberty.

Some prominent Afghan women politicians have once been bacha posh . This is, for instance, the case of Azita Rafaat, a member of the Afghan parliament, who returned to her original gender when she reached the age of marriage and was compelled to become the second wife of her cousin. After several failed attempts at producing boys, which provoked constant disputes between her and her in-laws, she decided to turn one of her daughters, Mehran, into a boy too. She considered her own experience as a bacha posh a positive one: it had increased her self-confidence and made her able to better understand the situation of women in the country. She is now a fervent advocate for womens rights at the Afghan National Assembly. Another famous case is Bibi Hakmeena, a councillor from Khost Province who dresses only like a man. Unlike other women, she wears a loose peran tomban (knee-length shirt and large trousers) and a black turban. Dressed in such a manner she is barely distinguishable from the men with whom she mixes. Bibi Hakmeena became a man at the age of ten when the Red Army invaded Afghanistan. With her one brother sent to study in Kabul and her younger brother too young to take up arms, the family lacked masculine protection. To get around the problem her father dressed her up as a boy and made her responsible for protecting her mother and younger siblings. He also took her to pol itical meetings and made her participate in the armed struggle against the Russians. Now in her forties, she never returned to womanhood when she reached puberty. Bibi Hakmeena, who never goes out without a Kalashnikov, explains that she never felt like a woman. A highly respected figure within her constituency, she is nicknamed king of the women because of her sensitivity to womens conditions (Hasrat-Nazimi 2011).

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence)»

Look at similar books to Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Kabul Carnival (The Ethnography of Political Violence) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.