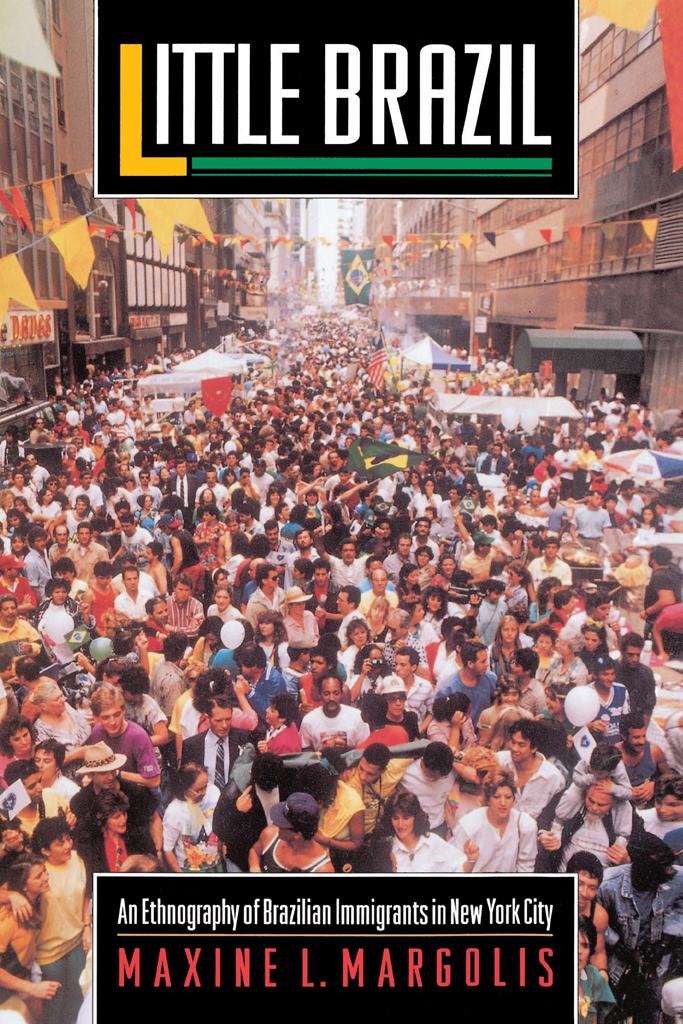

Copyright 1994 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Margolis, Maxine L., 1942-

Little Brazil : an ethnography of Brazilian immigrants in New York City / Maxine L. Margolis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-03348-X (cl.)

ISBN 0-691-00056-5 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-1-40085-175-1 (ebook)

1. Brazilian AmericansNew York (N.Y.)Social life and

customs. 2. New York (N.Y.)Social life and customs.

I. Title.

F128.9.B68M37 1993

974.7'1004698dc 93-13699 CIP

R0

IN MEMORY OF CHARLES WAGLEY

Student of Brazilian culture,

mentor extraordinaire,

and dear friend

No saiam do Brasil, fiquem aqui, me ajudem.

Dont leave Brazil, stay here and help me.

FERNANDO COLLOR DE MELLO,

in a televised address three days before being sworn in as President of Brazil, March 1990

PREFACE

Migration has a dual economic function: from the standpoint of capital, it is the means to fulfill labor demand at different points of the system; from the standpoint of labor, it is the means to take advantage of opportunities distributed unequally in space.

ALEJANDRO PORTES AND ROBERT BACH, Latin Journey

B RAZILIAN immigration to New York City and elsewhere abroad is not an isolated phenomenon. It is part of a global process in which emigrants from newly industrializing and less industrialized nations become strangers at the gate of the industrialized countries, seeking employment. With the globalization of international migration, Poles, Czechs, Albanians, and other Eastern Europeans are joining Turks and North Africans in the trek to Western Europe. Brazilians and Peruvians of Japanese descent are flocking to the land of their ancestors for jobs. Citizens of nearly every nation in South and Central America and the Caribbean are heading for the United States in search of work. There they encounter thousands more from India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Senegal, the Philippines, China, Korea, and coming full circle, Eastern Europe, all travelers pursuing a bit of the American economic dream.

The traditional push-pull explanations of international migration have proved inadequate in accounting for a worldwide phenomenon of such magnitude. Push-pull theorists assert that the catalyst for international migration is the imbalance in labor supply and labor demand in migrant-sending and migrant-receiving countries. But they tend to ignore macrostructural factors that enmesh these global movements, such as rising expectations in sending countries brought on by increased levels of education and media exposure to consumer patterns in advanced industrial states. Such macrostructural factors help explain why, as in the case of Brazil, international migrants are not generally from the most impoverished countries or from the poorest sections of sending nations, as pushpull theories would predict.

Proponents of push-pull scenarios for international migration generally emphasize individualistic responses, while structural analysts look to macroeconomic trade and investment flows between countries. To be sure, these approaches are not mutually exclusive, and both are useful, albeit at different levels of analysis. Structural factors shed light on the direction of large-scale migratory flows between nations and between different parts of the world, while push-pull factors and social network analyses are useful in explaining which individuals actually migrate, the distance they travel, and their specific destinations.

The movement of peoples from newly industrializing to industrialized states is in part fomented by what Alejandro Portes and Robert Bach call an invidious comparison between [industrialized countries] lifestyles and consumption patterns and those of sending countries. But more significant yet is the safety valve feature of international migration: its role in diffusing extremely difficult internal problems of migrant-sending nations. For example, capital-intensive industrial and agricultural development have created labor surpluses in many Latin American and other newly industrializing economies. These labor surpluses and structural adjustment measurescurrency devaluation, for example, and cuts in government servicesspur migration from these countries because they increase unemployment and depress wages and living standards, including those of the middle class.

Contrary to the stereotype of international migrants as people driven from their homes by poverty and despair, in recent years middle-class migrants from the industrializing world also have become major players in these global movements. One reason is that international migration helps ameliorate the problem of the overqualified in many sending nations. This problem arises when large numbers of professionals are trained and educated, but although their skills may be sorely needed at home, insufficent jobs are available in their fields at wages they deem adequate compensation for their many years of schooling. Brazil, once again, is an apt example. Given the realities of the labor markets in many developing nations, higher education and professional training have led to shattered expectations for social mobility. International migration takes some of the heat off the problem by siphoning off many of the disgruntled over-qualified.

But the global movement of these migrantswe might call them the educated surplusserves another purpose as well. Granted the low wages and underemployment that plague many newly industrializing nations, the remittance money that migrants send home from their jobs abroad helps subsidize the lifestyle of the middle class back home. Moreover, through the buttress of overseas migrants remittances, the state is relieved of some of the political pressure that it would inevitably face from a populace dissatisfied with low wages and limited economic opportunities. Just how important remittances are to the economies of some industrializing nations is evident from the figures for the Dominican Republic. An estimated $300 to $600 million a year is sent there by Dominican migrants living in New York City, a sum that makes remittances the countrys second largest industry.

International migration, however, is always a two-way street, and however much the powers that be in industrial countries loudly protest the waves of immigrants flooding their shores, their complaints serve to obfuscate an underlying reality: receiving nations also stand to benefit from these global currents. The industrial states, the primary destination of international migrant flows, are, after all, in the enviable position of having a nearly limitless supply of inexpensive labor clamoring at their gates. And in recent years advanced industrial countries such as the United States have been attracting skilled, highly motivated immigrants for even the most menial jobs. Moreover, through legislation and selective enforcement of immigration law, the state can not only create a profitable supply of cheap but powerless labor, but can partially regulate who passes through its portals.