This book was published with the generous assistance of the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation and the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation.

2010 THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

All rights reserved. Designed by Kimberly Bryant and set in Arno Pro by Tseng Information

Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America

Change Comes Knocking: The Story of the NC Fund (DVD) 2009 Video Dialog Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Korstad, Robert Rodgers.

To right these wrongs : the North Carolina Fund and the battle to end poverty and inequality in 1960s America / Robert R. Korstad and James L. Leloudis ; with photographs by Billy E. Barnes.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isbn 978-0-8078-3379-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8078-7114-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. North Carolina FundHistory. 2. Economic assistance, DomesticNorth Carolina

History. 3. PovertyGovernment policyNorth CarolinaHistory. I. Leloudis, James L.

II. Barnes, Billy E. III. Title.

HC107.N83P634 2010

362.580975609046dc22

2009052890

cloth 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

paper 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

I still think today as yesterday that the color line is a great problem of this century. But today I see more clearly than yesterday that back of the problem of race and color, lies a greater problem which both obscures and implements it: and that is the fact that so many civilized persons are willing to live in comfort even if the price of this is poverty, ignorance, and disease of the majority of their fellowmen.

w. e. b. du bois,

The Souls of Black Folk (1953)

If it may be said of the slavery era that the white man took the world and gave the Negro Jesus, then it may be said of the Reconstruction era that the southern aristocracy took the world and gave the poor white man Jim Crow.... And when his wrinkled stomach cried out for the food that his empty pockets could not provide, he ate Jim Crow, a psychological bird that told him that no matter how bad off he was, at least he was a white man, better than the black man.... And when his undernourished children cried out for the necessities that his low wages could not provide, he showed them the Jim Crow signs on the buses and in the stores, on the streets and in the public buildings. And his children, too, learned to feed upon Jim Crow.

martin luther king jr.,

Our God Is Marching On! (1965)

There can be no question but that in the South in general (or in the nation as a whole, of course) only an interracial movement of the poor can dig deeply into the root causes of poverty and exert the pressure necessary to alleviate and cure these causesand develop a genuinely democratic society.

john salter ,

community organizer in northeastern

North Carolina, 1968

Introduction

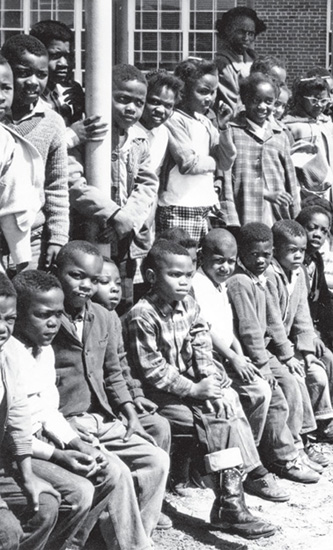

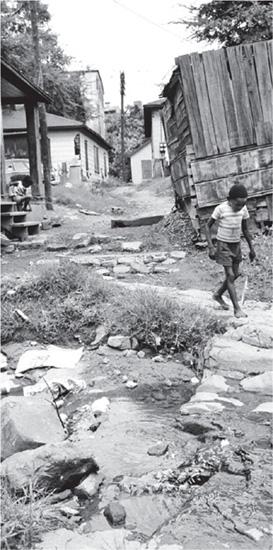

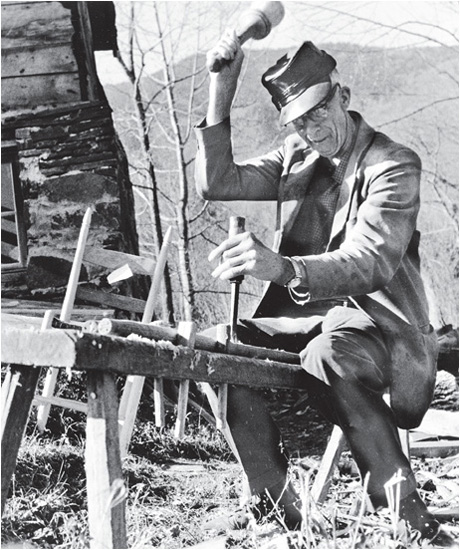

This book is about the politics of race and poverty in America. It tells the story of the North Carolina Fund, a pioneer effort to improve the lives of the neglected and forgotten poor in a nation that celebrated itself as an affluent society. Governor Terry Sanford created the Fund in 1963, at a time when the United States stood at a crossroads. A decade of civil rights activism had challenged the country to fulfill its promise of equality and opportunity. Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction had reformers raised such fundamental questions about the political and social foundations of the republic. But it was by no means clear how Americans would answer. Alabama governor George C. Wallace spoke for one possibility. In his inaugural address, delivered on the steps of the Alabama statehouse in January 1963, he pledged to defend Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever! Those words made Wallace the point man for a politics of fear and resentment, which eventually spread to communities across the land.

In North Carolina, Governor Terry Sanford offered a dramatic alternative. On July 18, six months after Wallaces swearing-in, Sanford announced the establishment of the North Carolina Fund, a unique five-year effort to stamp out the twin scourges of discrimination and economic deprivation. In North Carolina there remain tens of thousands whose family income is so low that daily subsistence is always in doubt, he explained. There are tens of thousands who go to bed hungry.... There are tens of thousands whose dreams will die. That anguish cried out for institutional, political, economic, and social change designed to bring about a functioning, democratic society. This, the governor proclaimed, is what the North Carolina Fund is all about. With those words, Sanford positioned the private nonprofit corporation and the state as the advance guard in what would soon become a national, federally funded war on poverty.

The Fund was overseen by a board of directors that included civic leadersmen and women, black and whitefrom across the state. It began its work with $2.5 million in financial backing from two local philanthropies, the Z. Smith Reynolds and Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundations, both of which were tied to influential banking and tobacco interests. The Ford Foundation, which had been investing in projects of social reconstruction in urban America, gave an additional $7 million. After passage of the Economic Opportunity Act and creation of the Office of Economic Opportunity ( oec ) in 1964, the Fund also became the primary conduit for the flow of federal antipoverty dollars into North Carolina. By 1968, it had received just over $7 million from the oeo and the Departments of Labor; Housing and Urban Development; and Health, Education, and Welfare. The Funds total five-year budget of $16.5 million roughly equaled the state of North Carolinas average annual expenditure for public welfare during the mid-1960s.

The Funds reliance on a combination of private and federal dollars was a calculated political tactic designed to ensure its independence. It allowed Sanford and his allies to bypass conservative state lawmakers and challenge the entrenched local interests that nourished Jim Crow, perpetuated one-party politics, and protected an economy built on cheap labor and racial antagonism. The Funds purpose, explained executive director George Esser, was to