NEW AFRICAN HISTORIES

SERIES EDITORS: JEAN ALLMAN, ALLEN ISAACMAN, AND DEREK R. PETERSON

David William Cohen and E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, The Risks of Knowledge

Belinda Bozzoli, Theatres of Struggle and the End of Apartheid

Gary Kynoch, We Are Fighting the World Stephanie Newell, The Forgers Tale

Jacob A. Tropp, Natures of Colonial Change

Jan Bender Shetler, Imagining Serengeti

Cheikh Anta Babou, Fighting the Greater Jihad

Marc Epprecht, Heterosexual Africa?

Marissa J. Moorman, Intonations

Karen E. Flint, Healing Traditions

Derek R. Peterson and Giacomo Macola, editors, Recasting the Past

Moses E. Ochonu, Colonial Meltdown

Emily S. Burrill, Richard L. Roberts, and Elizabeth Thornberry, editors, Domestic Violence and the Law in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa

Daniel R. Magaziner, The Law and the Prophets

Emily Lynn Osborn, Our New Husbands Are Here

Robert Trent Vinson, The Americans Are Coming!

James R. Brennan, Taifa

Benjamin N. Lawrance and Richard L. Roberts, editors, Trafficking in Slaverys Wake

David M. Gordon, Invisible Agents

Allen F. Isaacman and Barbara S. Isaacman, Dams, Displacement, and the Delusion of Development

Stephanie Newell, The Power to Name

Gibril R. Cole, The Krio of West Africa

Matthew M. Heaton, Black Skin, White Coats

Meredith Terretta, Nation of Outlaws, State of Violence

Paolo Israel, In Step with the Times

Michelle R. Moyd, Violent Intermediaries

Abosede A. George, Making Modern Girls

Alicia C. Decker, In Idi Amins Shadow Rachel Jean-Baptiste, Conjugal Rights

Shobana Shankar, Who Shall Enter Paradise?

Emily S. Burrill, States of Marriage

Todd Cleveland, Diamonds in the Rough

Carina E. Ray, Crossing the Color Line

Sarah Van Beurden, Authentically African

Giacomo Macola, The Gun in Central Africa

Lynn Schler, Nation on Board

Julie MacArthur, Cartography and the Political Imagination

Abou B. Bamba, African Miracle, African Mirage

Daniel Magaziner, The Art of Life in South Africa

Paul Ocobock, An Uncertain Age

Keren Weitzberg, We Do Not Have Borders

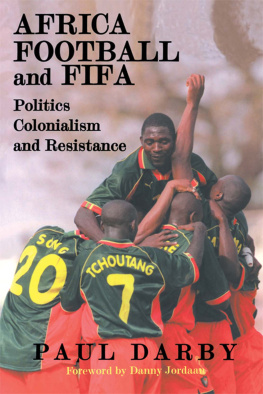

Nuno Domingos, Football and Colonialism

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

ohioswallow.com

2017 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

A substantially different version was published in Portuguese as Futebol e colonialismo: Corpo e cultura popular em Moambique by Imprensa de Cincias Sociais of the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon, 2012.

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Domingos, Nuno, 1976 author.

Title: Football and colonialism : body and popular culture in urban Mozambique / Nuno Domingos ; foreword by Harry G. West.

Description: Athens : Ohio University Press, [2017] | Series: New African histories | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017018181| ISBN 9780821422618 (hc : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780821422625 (pb : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780821445976 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: SoccerMozambiqueHistory. | SoccerSocial aspectsMozambique. | SoccerPolitical aspectsMozambique. | MozambiqueSocial life and customs.

Classification: LCC GV944.M85 D6613 2017 | DDC 796.33409679dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018181

Foreword

The bigger picture is sometimes best seen in the littlest details. According to Thomas Hylland Eriksen, the importance of anthropology lies precisely in its ability to examine large issues in small places. That is exactly what Nuno Domingos accomplishes in Football and Colonialism: Body and Popular Culture in Urban Mozambique.

At first glance, the work is about football as it was played in Loureno Marquesthe largest city and administrative center of the Portuguese colony of Mozambiquein the first half of the twentieth century. The work charts the development of the game from the founding of the first football clubs by British expatriates, to the establishment of satellites of Portuguese metropolitan clubs such as Sporting and Benfica, to the opening up of these clubs to African players including mostly elites of mixed racial heritage, to the eventual creation of an African Football Association whose players were mostly working-class Africans living in the poorer periphery of the city where their matches were mostly played.

Historians of football will, of course, be interested to learn more of the sporting context that produced such talents as Mrio Coluna and Eusbio, both of whom made their mark in European football in the mid-twentieth century. And footballs claim to be aif not theworld sport will only be strengthened by accounts of the enthusiasm with which urban Mozambicans of varied backgrounds embraced the game so long ago. Domingoss work is, however, far more than a historical account of the spread of a European (if only in its modern form) game to an African colony. The bigger picture with which this work engages is the relationship between colonized and colonizer, seen through the lens of that game.

As such, this account builds upon and extends a social science tradition that has produced rich results in African studies in recent decades, namely the study of popular culture. To date, studies of African popular culture have mostly focused on the arts, including sculpture, painting, music, dance, literature, cinema, and theater. Such work has rendered visible the dynamic interaction of tradition and modernity on the African continent, highlighting the ways in which African forms of expression have engaged with the lived experience of historical processes connecting the continent to a larger world, from colonialism, to revolutionary nationalism, to socialism, to neoliberalism. In the mix, Africans have adopted and adapted European genres of expression to their own ends and, as this body of work has shown, contributed profoundly to the global trajectories of these various forms.

Domingos himself adopts and adapts the popular culture approach to his ends in this study. He extends the approach to a realm too often ignored by historians and social scientists, namely sport. By seeing how football was played in urban Mozambique through the conceptual framework of genre, he dispenses with the assumption that a gamedefined as it is by a set of rulestravels unchanged from one social context to another. Like the arts, he shows us, football has been transformed by those who have played it in places like colonial Mozambique. But it is not the transformation of the game itself that most interests Domingos in this work. He is instead most interested in the larger issues of how the game of football did or did not transform those who played it in colonial Mozambique, as well as how they were or were not able to use the game to transform the world in which they lived.