The views and opinions expressed in this book do not necessarily express those of the United States government, past or present.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Jenn Bennett

Marketing by Kate McDonnell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Outsmarting apartheid : an oral history of South Africas cultural and educational exchange with the United States, 19601999 / edited with an introduction by Daniel Whitman ; with assistance from Kari Jaksa.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5121-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Anti-apartheid movementsSouth AfricaHistory. 2. Anti-apartheid movementsUnited StatesHistory. 3. Educational exchangesSouth AfricaHistory20th century. 4. Educational exchangesUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. South AfricaRelationsUnited States. 6. United StatesRelationsSouth Africa. I. Whitman, Daniel, editor of compilation.

DT1757.O87 2014

305.80096809045dc23

2013021458

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

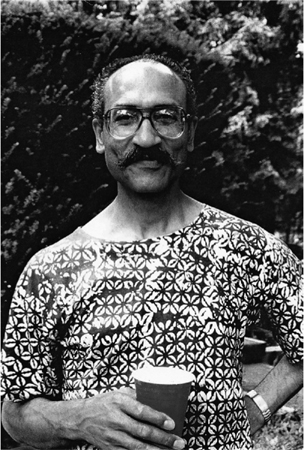

Outsmarting Apartheid is inspired by, and dedicated to,

the memory of

Bart Rousseve (19411994)

Bart Rousseve

Introduction

I first met South Africans in the summer of 1978. As interpreter for francophone Africans visiting the United States with Operation Crossroads Africa, I found them mixed in with groups of young African leaders brought in from twenty to thirty countries at a time.

Traveling across the wilds of northern New Jersey from JFK airport to the Princeton campus for orientation, one collared South African clergyman made quick eye contact with me in the airport shuttle and undertook to explain his bizarre country: Brother! he said with deep belly laughs. You cant imagine how strange my country is. So strange, that the penalty for a black man sleeping with a white woman is a year in prison!

I knew apartheid South Africa had peculiar rules and restrictions, but wasnt yet versed in the particulars.

Well, Brother, let me tell you, the clergyman continued. It was worth it, every minute of it! He laughed even harder.

There was something exceptional about the South African visitors to the United States in those daysmost but not all of them black and colored, to use the South African nomenclature. Cloistered but worldly, committed to social and political changes that seemed unlikely at the time, they persevered through minefields of distrust laid by Africans of other countries. Surely, if they were allowed by the apartheid regime to travel to international fora, they must be stooges, or worse: spies.

I interpreted French through tense and arduous hastily arranged meetings long into the night in the Princeton dorms. I tried to keep a neutral tone because I was the uninvited but necessary guest to get the messages across. I tried to convey them without interpretative body language or innuendo, as Malians, Nigerians, Ivoirians, Liberians, and others subjected South Africans to harsh scrutiny. Opponents at home to their own system at personal risk and cost, the South Africans weathered the suspicions of the others, in tranquil Princeton, that they were in fact the regimes patsies. Eventually they gained the others trust. It wasnt easy.

Profound change in South Africa was imminent, but no one knew it then. Coinciding in time with events and efforts that corroded communist dictatorships in Eastern Europe to the breaking point, similar patterns played out in South Africa. Along with others, the United States Embassy pushed the envelope of transformation, hastening a painful process and short-circuiting the violence everyone expected. U.S. diplomats and their South African local employees in Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town, and Pretoria engaged daily in brinksmanship with police, ministry officials, and educators of the apartheid regime. They managed to get majority South African students and professionals to the United States in significant numbers, cracking open the seemingly unshakeable clouded glass ceilings. In effect they outsmarted apartheid every day for a twenty-year period.

Sharpeville 1960. The Soweto Uprising 1976. Constructive engagement, military and economic boycotts, debates on American campusesthe brew was volatile. A countrys wealth, talent, and beauty lay largely unrealized, while tantalizing information began to circulate within the country about the vibrant changes on the outside, in the United States and other dynamic societies, overtaking South Africa in most forms of development.

Even as few could have predicted the events in Berlin of 1989, likewise few could foresee that apartheid in South Africa might yield a more normal society, short of the bloodbath many expected with or without change. A just society, with economic and social outlets for all South Africans, and basic parity in a country of income extremes seemed unattainable goals. Even the movements of the privileged within the systemmany of whom sought justice in their societywere blocked overseas, where they were mistrusted and shunned. They left in waves of emigration in the 1970s and 1980s.

The work of U.S. officials and their employees during that period richly deserves recognition for their contribution to the outcome two decades later. Their story is largely untold outside their own circles. This volume gives voice to a number of the witnesses: officials, local employees, and South African grantees of all races who made it to the United States during turbulent times and later took up the reins of leadership in the new South Africa of the 1990s.