Copyright 2014 , Chris Benjamin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, Yonge Street, Suite 1900 , Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5 .

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3731 Mackintosh St, Halifax, NS B3K 5A5

() - 4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

NB1077

Interior design: John van der Woude Designs

Cover design: Heather Bryan

Cover photograph: Sisters of Charity, Halifax, Congregational Archives

I Lost My Talk by Rita Joe, from Songs of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mikmaw Poet reprinted courtesy of Breton Books.

Images on pages 37 and 41 Copyright Government of Canada. Reprinted with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada (2013).

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Benjamin, Chris, 1975-, author

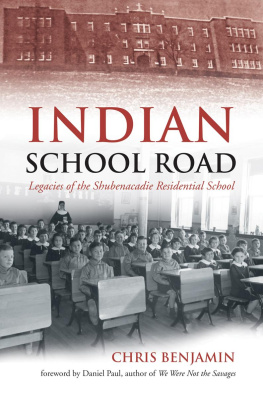

Indian school road : legacies of the Shubenacadie Residential

School / Chris Benjamin.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77108-213-6 (pbk.).ISBN 978-1-77108-214-3 (mobi).ISBN 978-1-77108-215-0 (html)

1. Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. 2. Micmac Indians

Nova ScotiaResidential schools. 3. Abused Indian childrenNova

ScotiaShubenacadie. 4. Indians of North AmericaNova Scotia

ShubenacadieResidential schools. I. Title.

E96.6.S58B45 2014 371.82997343071635 C2014-903184-X

C2014-903185-8

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund ( CBF ) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through Film & Creative Industries Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with Film & Creative Industries Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

This is for my children. Because even at its ugliest,

the truth is less repulsive than lies.

I Lost My Talk

I lost my talk

The talk you took away

When I was a little girl

At Shubenacadie school.

You snatched it away;

I speak like you

I think like you

I create like you

The scrambled ballad, about my word.

Two ways I talk

Both ways I say,

Your way is more powerful.

So gently I offer my hand and ask,

Let me find my talk

So I can teach you about me.

Rita Joe

Contents

Foreword

BY DANIEL PAUL, AUTHOR OF

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES

When despotic Caucasian aristocrats ruled over most European nations to maintain their positions, they used terrorism to keep their citizens controlled, which was paramount for their very existence. Thus, when their representatives discovered non-white civilizations where the people ruled it was in their best interests to destroy such civilizations before their democratic ideals spread to their own populations. To make the eradication seem really desirable among their subjects, they undertook steps to dehumanize the populations of such democracies by demonizationimplanting in the minds of their subjects a picture of bloodthirsty, mindless savages. Such practices were used brilliantly in the Americas; so thoroughly implanted was the white supremacist propaganda that the grotesque negative effects are still being felt by Canadas First Peoples today.

To refute the aforementioned propaganda, Ill simply relate some of what the Mikmaq Nation didnt have and what it did have. Five hundred years ago the Mikmaq did not burn people at the stake, did not use humans as work-animals, did not have bedlams and poor houses for their sick and disadvantaged, did not castrate young boys so that their sweet voices could be heard by the elite for a longer period, did not have debtors prisons, did not practice any kind of intolerance, and so on. They did have democracy. There was no poverty among them, divorces were available and a female was not beheaded to dissolve a marriage, there were no dictators and no elite: the people ruled, freedom and justice for all, and so on. Ill leave it to the reader to decide which was the most desirable civilization.

In the early stages of the European invasion of the Americas, out-and-out genocidal practices were liberally used to exterminate indigenous populations, for instance the Beothuk were wiped out and proclamations for the scalps of Mikmaw men, women, and children were issued by Massachusetts governor William Shirley ( 1744 ) and Nova Scotia governor Edward Cornwallis ( 1749 ).

By the time Canada was created in 1867 , such barbarous practices had been replaced with a gentler methodology: severe malnutrition was permitted to be quite common among the tribes and medical assistance was minuscule. Thus, even minor illnesses more often than not proved fatal. This neglect worked toward the goal of eliminating what Caucasian politicians, bureaucrats, and citizens deemed the Indian Problem. Indian Commissioner Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott in 1920 stated, I want to get rid of the Indian problem...Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.... But progress was slow.

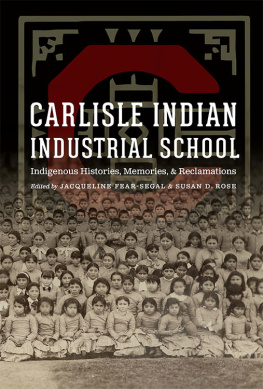

In the late 1800 s new tools to expedite the process were devised: Indian residential and day schools. The sole reason for their establishment was to take the Indian out of the Indian. This story by Chris Benjamin about the Shubenacadie residential school is your story, not ours. It reveals a sin that is to Canadas everlasting shame, an attempt to exterminate its Indigenous peoples by assimilation. Not even South Africas apartheid rivals the effort: apartheid was invented to separate the races; Canadas assimilation policies were implemented to exterminate.

Chriss book reveals the pain that white supremacist racism can inflict upon a people of colour. It demonstrates vividly that the wounds and scars accumulated by the incarcerated children will not heal in their lifetimes.

Introduction: Why and How

Oppressors always expect the oppressed to extend to them

the same understanding so lacking in themselves.

Audre Lorde

Unsettling

Here is what I found first: a recurring nightmare. Me wandering the black and white halls of the old building, as seen only in photographs, pristine but steeped in an old rotten stench. The facts playing hide-and-seek within the walls. Finding only a sense of lurking, dishonest evil. What fools mission was this? What right did I have to come here?

Dorothy Moore lived here as a girl. Sister Dorothy Moore shes now called, a well-known Mikmaw Elder who once said to a luncheon at St. Marys University that white people owe First Nations people an explanation for residential schools. Now, a couple decades after she said it, most of the creators of the system and its schools are dead or very, very old. But Im alive, and fairly young. I have questions about residential schools, particularly the one that ran in my home province of Nova Scotia. The big one is: what the hell were we thinking?

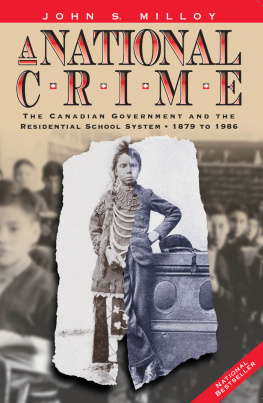

In her probing book, Unsettling the Settler Within, Paulette Regan wonders why, with all the talk of the Aboriginal peoples need for healing, arent more of us looking at what it means to be a colonizer and our own need to heal and decolonize. European-Canadians committed what John S. Milloy, a Canadian Studies professor at Trent University, calls a national crime, in his book of the same name. He quotes a residential school survivor who told researchers in 1966 , This is not my story but yours. Milloy adds, It is