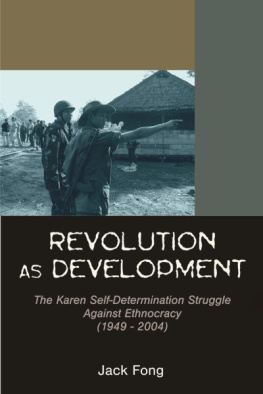

Revolution as Development: The Karen Self-Determination Struggle against Ethnocracy (1949-2004)

Jack Fong

Universal Publishers

Boca Raton, Florida

Revolution as Development: The Karen Self-Determination Struggle against

Ethnocracy (1949-2004)

Copyright 2008 Jack Fong

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

Universal Publishers

Boca Raton, Florida USA

2008

ISBN-10: 1-59942-994-2 ( paper )

ISBN-13: 978-1-59942-994-6 ( paper )

ISBN-10: 1-61233-007-X ( ePub )

ISBN-13: 978-1-61233-007-5 ( ePub )

www.universal-publishers.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fong, Jack, 1970-

Revolution as development: the Karen self-determination struggle against ethnocracy (1949-2004) / Jack Fong. -- 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59942-994-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-59942-994-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Ethnic conflict--Burma. 2. Karen (Southeast Asian people)--Burma. 3. Conflict management--Burma. 4. Burma--Politics and government--1988- 5. Burma--Social conditions--1988- I. Title.

HN670.7.S62F66 2008

305.895--dc22

2008003104

Table of Contents

..

The Epic

The Journey

Overview of Text

Development Perspectives in a Historical Context

a. 1950s

b. 1960s

c. 1970s

d. The 1980s and 1990s: Neoliberal Development

e. Criticisms of the Neoliberal Model

Beyond Neoliberal Development: Alternative Development

Definitions of Ethnicity

Theories and Debates on Ethnicity

a. Ethnicity as a Primordial Entity

b. The Social Construction of the Ethnicity

c. Ethnicity as Political Instrument

d. Ethnicity as Rational Choice

The Function of Ethnicity and Systemic

Crisis in Ethnodevelopment

Ethnodevelopment

Critique of Stavenhagen

First Phase: Ba U Gyi and the Four Principles

of the Karen Revolution

Second Phase: Ideological Strain between

Mahn Ba Zan and Hunter Tha Hmwe

Third Phase: Bo Mya and the Nationalist

KNU in the 1980s

a. Internal Colonization through the Four Cuts

b. The 1988 Democracy Crackdown:

Effects on the KNU

c. Problems with the CPB

1990 General Elections Results

Bo Mya and the KNU in the 1990s: New Challenges

a. DKBA and the Fall of Manerplaw

b. Ceasefires

c. The Mae Tha Waw Hta Agreement:

Hopes and Consequences

The Four Cuts upon the KNLA

The Four Cuts upon Civilian Karen

a. Effects upon Villagers and Villages

b. Effects of Forced Labor upon Villagers

c. The Rape of Karen Women

d. Internally Displaced Peoples (IDPs)

e. Refugees

f. The Destruction of the Karen Regional

Political Economy

The Karen National Union

The Karen National Liberation Army

The Forestry Department

a. Kaser Doo Wildlife Sanctuary

b. The Significance of Teak

Health and Welfare Department

Education Department

Thailand

Logging

China

Additional Players

Petropolitics

a. Consequences

b. Justifications Used by the Oil TNCs

National Day, January 31, 2004

a. Bo Mya Talks with International Journalists

b. Colonel Nerdah Mya Grants Interview to

Australian Journalist

c. Interviewing Pastor Lah Thaw

Interview of General Bo Mya by

Mizzima News: February 20, 2004

Additional Ceasefire Issues

The Future of Karen Liberation Ethnodevelopment

a. The Transcommunal KNU

b. Transnational Self-determination

c. Self-determination on the

Information Highway

d. A Role for the United Nations?

Karen Liberation Ethnodevelopment as a Form of Nationalism

a. Democratic Politics or Ethnodemocratic Politics?

b. The Future of Military-rule in Burma

Implications of the Karen Struggle for

Understanding a Materialist Ethnicity

a. Ethnicity Disentangled from Class Dynamics

b. Ethnicity during Systemic Crisis

c. Ethnicity during Political Maneuverings

Sociological Implications of Ethnodevelopment

Development Studies

Acknowledgements

Before we begin, I want to express my deepest gratitude to all the kind people abroad and at home that have supported this project. At the University of California, Santa Cruz, I begin by first thanking my mentors: historian of South Asia Dr. Dilip Basu, ethnic and indigenous scholar Dr. John Brown Childs, development scholar Dr. Ben Crow, jurisprudence scholar Dr. Hiroshi Fukurai, political sociologist Dr. Craig Reinarman and Dr. Guillermo Delgado from the Latin American and Latino Studies Department. They challenged me with very profound questions regarding the Karenmany of which I hope were answered in this work.

My gratitude also goes to Stephen McNeil, Regional Director of Peacebuilding and Relief Work for the American Friends Service Committee based out of San Francisco, California. Stephen was kind enough to take time from his busy schedule to meet with me as well as provide for me insight into the world of Karen refugees. I would also like to thank Dr. Rodolfo Stavenhagen, whose brief correspondence with me through email regarding ethnodevelopment has helped me immeasurably. My application and readjustment of Dr. Stavenhagens ideas represent the core of my work.

In Thailand, I also cannot overemphasize my gratitude to my childhood friends, Jane Ritdejawong and Owen Silpachai. It is absolutely no exaggeration to say that this research would not have materialized were it not for Janes assistance. As an accomplished television journalist and producer, Jane visited the Karen State of Kawthoolei after the 1995 fall of its capital, Manerplaw. She thus had first-hand experience with the suffering experienced by the Karen. Because of Jane, I see an important role journalists can play with field researchers conducting ethnographic research in the context of systemic crisis. Owen, also a childhood friend, was gracious enough to provide for me one of his dwellings in Bangkoks Silom District. Being situated in this part of the city allowed me to be close to important venues for publishing/printing, internet use, money exchange, and public transportation. I was able to finish the rudimentary sections of my research in his Silom condominium. Logistically, Owens assistance was priceless.

In Kawthoolei, I have to thank Colonel San Htay (pseudonym) for taking time out from his extremely busy schedule to meet with me. From the day we crossed the Moei River to arrive at Mu Aye Pu, until my last meeting with him in Bangkok prior to my return to the United States, I have always felt a deep sense of respect for his courage in navigating an epic struggle against oppression. I am also very thankful for Col. San Htays assistants, also pseudonymously referred to Tha Doh, Maung Baw, Hope, and Roni who were kind enough to assist me at Mu Aye Pu and beyond Mu Aye Pu. Much gratitude also goes to the KNLAs Captain Tony who, on leave from the frontlines, enthusiastically shared with me his views on the Karen struggle.