International Standard Book Number: 0226559904

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79103932

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1970 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved

Published 1970

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-226-55990-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-226-55992-6 (e-book)

PIONEERS FOR PROFIT

Foreign Entrepreneurship and Russian Industrialization, 18851913

John P. McKay

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO & LONDON

To Jo Ann

MAPS

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN FOOTNOTES

A.E., Brussels | Archives du Ministre des Affaires Etrangres, Brussels |

A.E., Paris | Archives du Ministre des Affaires Etrangres, Paris |

A.N. | Archives Nationales, Paris |

B.U.P. | Archives de la Banque de lUnion Parisienne, Paris |

C.C. | Correspondance Commerciale (commercial series of the French consular correspondence) |

C.I.C. | Crdit Industriel et Commercial, Paris |

C.L. | Archives du Crdit Lyonnais, Paris |

C.N.E.P. | Comptoir National dEscompte de Paris, Paris |

E.M. | Archives de lEcole des Mines, Paris |

P.R. MSS | Company records of the Forges de la Providence Russe, Marchienne-au-Pont, Belgium |

Note: All dates are given in the order of day-month-year; thus 351897 means 3 May 1897.

PREFACE

This study investigates the role of foreign entrepreneurship in Russian industrialization between 1885 and 1913. My purpose is to go beyond work on the statistical dimensions of large external investment in Russian industry and to understand the actual processes, mechanisms, and contributions of active foreign entrepreneurship. In doing so I have focused on three distinct problems: the pattern of enterprise and investment as practiced by business leaders of the advanced countries of western Europe before the First World War; the pattern of foreign participation in Russian industry and its influence on accelerated Russian growth in this period; and finally the nature of relations that existed between economically advanced foreigners and relatively backward Russians during development. All of these are related to vexing contemporary problems, and therefore I have gladly run the risks of didactic history.

My work is based largely upon previously unutilized private business archives in western Europe, and of course public archives as well. These archival materials are discussed in the bibliography. They permitted me to study a large number of French, Belgian, and German firms operating in Russia. Published Russian material has proved to be less valuable, but it has been carefully examined and important on occasion. There are two obvious omissions which are connectedmost English entrepreneurs and the petroleum industry. Originally I had intended to analyze the petroleum industry, which was dominated by foreigners, and particularly Englishmen. Finally it seemed best to examine the rapid rise of the entire Tsarist petroleum industry in a separate study. I hope to do this at a later date.

are thus meant to reinforce each other and sharpen our understanding of the performance of the representative foreign entrepreneur.

A word of explanation concerning the problems of Russian proper names and transliterations is necessary. Within the text I have generally used the accepted English spelling for place names, and I have transliterated proper names according to the Library of Congress system with slight modifications. To aid the reader in identifying different enterprises, I have added an appendix of major firms discussed. This appendix gives the original titles of firms in either French or Russian as well as the firms English equivalent as found in the text.

In researching and writing this study I have been aided and encouraged in many ways by many people. Although it is impossible to do justice to this support, a few acknowledgements may express my gratitude. I would like to thank: the staff of the Interlibrary Loan Service at the University of California, Berkeley, for tracking down many obscure volumes; various archivists and directors in Europe, and especially those of the Crdit Lyonnais and the Banque de lUnion Parisienne; and the Foreign Area Fellowship Program and Dr. James Gould, for generously supporting my work in this country and abroad. An earlier version of chapter nine first appeared in Business History Review, whose editors kindly granted me permission to use it here. In the academic world I wish to single out for their aid: Professor Olga Crisp of London, my colleagues Professors Ralph Fisher and Benjamin Uroff, Professor Gerald Feldman of Berkeley, and Professor David Landes, my thesis advisor, who gave me invaluable aid and criticism, as did Professor Henry Rosovsky. Professors Landes and Rosovsky first stimulated and then channeled my interest in economic history. They may rightly claim a large measure of whatever credit this study deserves, without, of course, being in any way responsible for its shortcomings. Lastly, I am very grateful for Jo Anns constant help and encouragement.

Part I

Dimensions of Entrepreneurship

INTRODUCTION

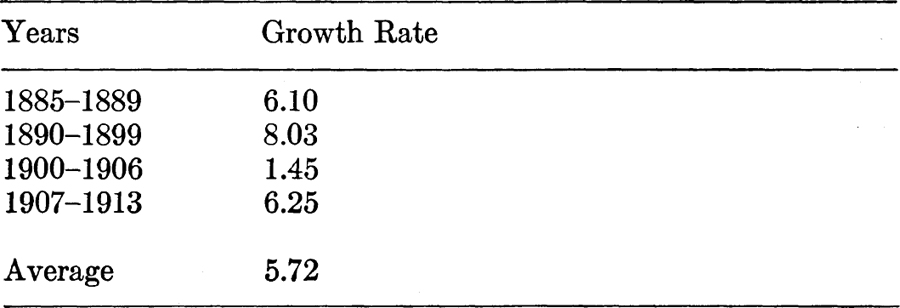

In the latter part of the nineteenth century the ever widening waves of the Industrial Revolution launched in Great Britain a century earlier broke upon economically backward agrarian Russia with great force. Military defeats and economic stagnation in the 1850s had forced a hesitant feudal society to begin in earnest the arduous task of modernization and industrialization. Then in the 1860s and early 1870s a whole series of developmentssuch as the emancipation of the serfs, the real beginnings of a railroad system, an expanding internal market, and the creation of a considerable banking systemhelped establish the preconditions of modern economic growth. The initial overall effect of these changes was limited, however, and it was a generation before the tempo of industrial progress quickened to revolutionary proportions in the 1890s. After the Russian industrial revolution of that decade (or big spurt or take-off, to use somewhat analogous current terminology), the pace of industrial development marked time during the serious depression from 1900 to about 1908. But it recovered impressively and was probably self-sustaining in the second surge, which lasted from 1909 to the outbreak of World War I. The pattern of two great booms broken by a long depression may be seen in .

The rate of growth for Russian industrial production shows.

Table 1

ANNUAL GROWTH RATES OF RUSSIAN INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION, 18851913

(In Percent)

SOURCE: Alexander Gerschenkron, The Rate of Growth of Industrial Production in Russia Since 1885, Journal of Economic History 7 Supplement (1947): 149.

NOTE: For the years 189499 the growth rate was approximately 9 percent; for 191013, approximately 7.5 percent.

At the same time the weight of the large and backward agrarian sector, the rapid rate of population increase, and the very low level of industrial development in 1860 (or 1890 for that matter) meant that Russia remained far behind other industrial nations in 1913 in all per capita comparisons of income or consumption in spite of its industrial achievement after 1885. In 1913 per capita income in Russia was only 101.4 rubles, as opposed to the equivalents of 300.4 rubles in Germany, 460.6 rubles in Great Britain, and 682.3 rubles in the United That rapid growth left Russia poor in absolute and comparative terms probably helps account for the great divergency of judgments concerning the nature of the Russian economy on the eve of the First World War and related historical what-might-have-beens. Those drawing an essentially optimistic interpretation stress (among other things) the relatively high and sustained