The Fire This Time

God gave Noah the rainbow sign

No more water, the fire next time!

Traditional

JAMES ARTHUR BALDWIN was born in Harlem in 1924. The out of wedlock child of a mother from the South, he was adopted by her husband, a store-front Pentecostal minister who raised him along with their children as his own. Baldwin distinguished himself early on as a precocious writer, and also as a child minister. His crisis of faith, which led to his abandoning the pulpit in high school, became the basis for much of his adult writing.

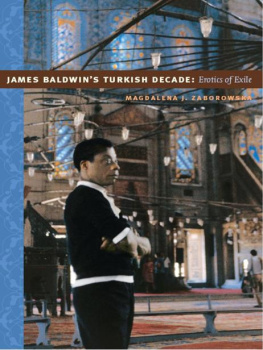

After spending two years living in Greenwich Village and trying to make a living as a reviewer and writer by taking odd jobs along the Northeastern Corridor, Baldwin decided to flee the country of his birth, hoping for a better racial climate and a place where he could concentrate on his writing. In 1948 he settled in post-World War II France, but found the situation only slightly better in terms of bias against racial minorities, and it was even more difficult to make a living. Through the kindness of friends, especially his lover, the Swiss Lucien Happersberger, Baldwin eventually finished his first novel in a small village in Switzerland. After a time he found an American publisher in Alfred A. Knopf, and in 1953 that novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was hailed as a critical success and as the debut of an important new voice. Baldwins next novel, 1956s Giovannis Room, whose main characters were white men and whose theme was homosexual love, was considered highly controversial. Knopf refused to take the book, but, by and by, it found a home first with a British publisher and then with the Dial Press, and was widely admired for its daring.

During this period the self-exiled Baldwin began to visit his home country to cover the accelerating civil rights movement in Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia, and other places. His writings were collected in 1955 as Notes of a Native Son, which was considered one of the most articulate accounts not only of the freedom movement but of the state of African Americans in American Society.

The New Yorker commissioned Baldwin to write an article about the Honorable Elijah Muhammad in 1962. The mentor of Malcolm X and the founder of the fast-growing and important Nation of Islam, the religious leader agreed to meet with Baldwin in his Chicago mansion. The resulting account became the basis of the article Down at the Cross: A Letter from a Region of My Mind and later the major part of the book The Fire Next Time. This 1963 work became an instant best-seller; Baldwin graced the cover of Time magazine, and the event marked a significant turning point both in the life of Baldwin and for the civil rights movement.

In the ensuing years Baldwin became a prolific author, publishing four novelsAnother Country (1962), Tell Me How Long the Train Has Been Gone (1968), If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), Just Above My Head (1979)four nonfiction worksNobody Knows My Name (1961), No Name in the Street (1972), The Devil Finds Work (1976), and The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1986)and many plays and short stories. He became recognized as a major voice of Black America and was much in demand as a speaker and lecturer. He became acquainted with such leaders as Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Robert F. Kennedy, and with many of the renowned writers, musicians, and actors of his day.

After years of traveling back and forth between America, France, and Turkey, he settled in the south of France, in an estate in Saint Paul-de-Vence, where he lived until his death in 1987.

Baldwins prose is marked by Biblical rhetoric and a love for nineteenth-century writers, and his elaborate sentences and formal tone gave him a singular style among African American writers. His themes also arose from both agape (unselfish love) and a Protestant belief in the power of redemptiona redemption that he hoped would come to his homeland. He held himself to a high standard of truth-tellinghard truths, difficult truths, truths about raceand he admitted that, in a sense, he had never really left the pulpit.

At the end of his seminal essay Notes of a Native Son, he wrote:

It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in ones own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all ones strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair.

A Change is Gonna Come: A Letter to My Godson

One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us. But white Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them. And this is also why the presence of the Negro in this country can bring about its destruction. It is the responsibility of free men to trust and to celebrate what is constantbirth, struggle, and death are constants, and so is love, though we may not always think soand to apprehend the nature of change, to be able to be willing to change. I speak of change not on the surface but in the depthschange in the sense of renewal.

The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin

Dearest Jailen,

Nine months before you were born, your grandfather, Mr. John Wallace Brown, died.

In every aspect but one, he was my father. I first met him when I was five years old, visiting your grandmothers home in Harlem, USA. He took a shine to me straightaway. Recordings exist of me asking him silly questions (Can you eat a thousand biscuits?). He took the entire family to Chinatown, I remember, and he took me to his gym. Your grandfather had been a boxer, but by the time I met him, in his late thirties, he had become a trainer of other boxers. The gym was in uptown Manhattan in the 150s, a dankish, run-down place, smelling of sweat and blood and smelling salts, but it held my fascination for decades. (A few years before he died, I casually mentioned to your mothers father that I had read that the great jazz trumpeter Miles Davis liked to box. Your grandfather said, Of course, he knew that. Davis used the same gym. You saw him, he told me.)