W ait, what? Japan? What does Japan have to teach us about happiness?

A lot, as it turns out, and thats something that took me years to figure out, and Im still puzzled and trying to make sense of it all. Key matters led me astray from the way I was brought up to think about happiness.

In Japan, happiness isnt a private experience. And happiness isnt really a goal. Acceptance is the goal.

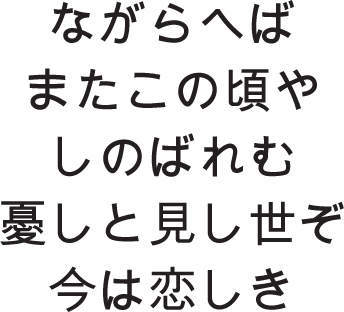

W hat Japan does at its best, and what we can learn from its culture, is how to ward off the pain of being alone in the world. Accepting reality, past and present, and embracing things that dont last are fundamental to life in Japan. Spending time in Japan, studying its culture, and trying hard to figure out how people there go about planning, organizing, loving, and seeing themselves and nature have changed how I see and deal with stress.

Not everyone succeeds at being part of the multitude of groups in Japan, and isolation is a famous problem, as it is in the West with the elderly, the marginalized, and those with chronic mental illness.

But there are huge differences. Options exist for inclusion in Japan, from communal bathing to safe public parks to huge shrines and temples throughout the country that are open to all. A lot of mingling goes on (since the Taisho era, 19121926, but not before), thanks in part to Westernization that broke down barriers and hegemonies. Groups are central to existence from very early ages with kids all dressing the same and eating the exact same school lunches. Expectations are so obvious and widespread that a lot goes unspoken: you know how you are supposed to behave in Japan at home, in school, in shops, in restaurants, and at workand these expectations dont vary much from person to person (although biases about gender and age and homogeneity are embedded and inhibiting).

Most of all, who you are as a human being in Japan, your self-identity, is formed as much by your group affiliations as by your quirks, opinions, and likes and dislikes.

Growing up in the United States, I adhere to our broad cultural opportunities: the can do spirit, the message of Yes, I can, the extraordinary openness and creativity, the willingness to try new approaches to get things done, the ferocity of individualism.

This is where Japan comes in.

Observation, listening, being silent, taking things in, considering problems as challenges, being far less reactive, and, above all, practicing acceptance: these are at the pinnacle of how you relate to yourself and others. While these behaviors all exist elsewhere, of course, as they are characteristic of our species, in Japan they are the cornerstones of institutional and systemic development.

Knowing that who I am has a lot to do with who am I with is liberating. The road to self-analysis and self-satisfaction is endless, ironically confining, and peculiarly isolating.

Who needs privilege when you can have affiliation?

No place has added greater balance to my life, calm, patience, respect for silence and observation, and acceptance of how community and nature matter more than ones needs. The individualism we prize in the West is supplemented by an awareness that lifes greatest pleasures come from satisfying others.

W hen others suffer, and we are empathic, our well-being is diminished. By this I mean: when we exercise our empathy, it implies absorbing the pain of others. As a clinician, when I hear, for example, terrifying narratives of loss, shame, and isolation, my well-being is diminished. This explains, in large part, why those suffering in ways evident to others are often shunned, blamed, or feared. The more we empathize with the pain of others, the more we recognize that their condition is part of our identity.

Think of it in the most pragmatic ways: if your child, spouse, parent, or dear friend is suffering, your well-being, because you feel part of them, and because they are in your heart and consciousness, is diminished. If my son or daughter or wife is suffering, I cant think about being happy.

Quite capable of creating my own stress, rather skilled at it, in fact, and coming from a family where stress was wholly normalized, I have had a tendency to repeat the same familiar mistakes.

And its not just the personal. It never ishow could it be?

When I interview people at my job three mornings a week at the Department of Transitional Assistance in Dudley Square, Roxbury, Massachusetts, doing disability evaluations among the homeless or impoverished or abused or recently incarcerated, and then drive back to my tony neighborhood, which is only five miles away, I can see in very stark relief that achievement and safety have far less to do with personal drive than with race, gender, and economics.