Oceans of Grain is the best work of history I have read in a very long time. Witty and wise, it reveals how conspirators and heads of state, workers and entrepreneurs, and philosophers and economists turned the human struggle for daily bread into wars and empires, revolutions and conquests, feasts and famines. It takes readers from the granaries and ancient trade pathways of Europe to the US Civil War and the overthrow of slavery, the founding of empires, the slaughterhouses of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, and, finally, to our contemporary, interconnected, and profoundly unequal world. Along the way, Scott Reynolds Nelson introduces us to the individuals who made and remade this world. Some are welcome new acquaintances and otherslike Abraham Lincoln and Vladimir Leninare shown in such new light that it feels as if we are meeting them for the first time.

Angela Zimmerman, George Washington University

Copyright 2022 by Scott Reynolds Nelson

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images h.yegho / Shutterstock.com; Universal History Archive/UIG / Bridgeman Images

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: February 2022

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nelson, Scott Reynolds, author.

Title: Oceans of grain : how American wheat remade the world / Scott Reynolds Nelson.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021032198 | ISBN 9781541646469 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541646452 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Wheat tradeUnited StatesHistory. | Wheat tradeHistory. | World history.

Classification: LCC HD9049.W5 .U66 2022 | DDC 338.7/61664722dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021032198

ISBNs: 9781541646469 (print), 9781541646452 (ebook)

E3-20220121-JV-NF-ORI

To my grandmother, Mildred (Mimi) Lofquist Brown (19122009), whose grandparents Mormor and Morfar left Sweden in 1887 after living through what she called the real Great Depression. She taught me to darn a sock, hem a torn pocket, and save a jam jar for the next depression.

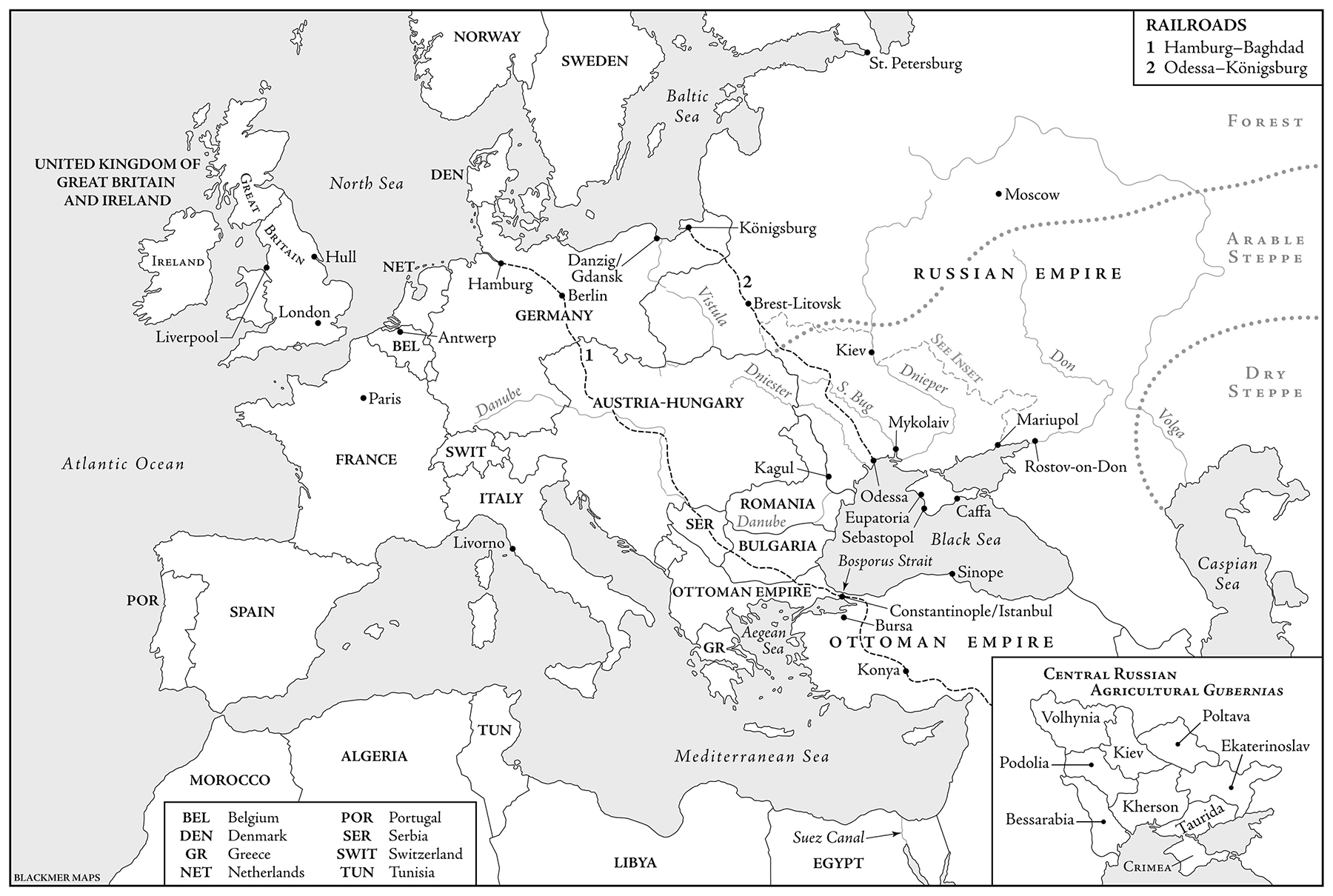

Oceans of Grain: The region that is sometimes called Europe on the left, its Black Sea breadbasket on the right, and the vital pinch point on the Bosporus Strait, c. 1912

Kate Blackmer

I N THE SPRING of 2011, I first flew into Odessa to research an international financial crisis, but not the one you have probably heard about. Two and a half years earlier, on October 1, 2008, I had written an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education predicting that problems with the mortgage market suggested a deeper problem with international trade that could hinder bank lending and lead to a global depression. I knew this, I wrote, because I saw similarities between modern problems with mortgage banking and my obsession: the panic of 1873. My editor asked me to conclude with a few paragraphs about what might happen if 1873 were similar to 2008. I predicted a steep decline in trade, widespread unemployment, hoarding of cash by financial firms, shifts in the currency used for international trade, scapegoating of immigrants, and finally a surge of nationalism and tariffs. Newspapers all over the world translated and reprinted my article even as the stock market began to plunge.

By 2011 I had finished a book about the American origins of financial panics, which I argued had much to do with drastic changes in commodity prices. Newspaper reporters were flying to the Arab world because of protests there, but as a historian I was heading to Odessa. Egyptian protesters called for bread, freedom, and social justice in 2011. I was thinking about calls for bread, freedom, and justice in the French Revolution of 1789, the downfall of Sultan Selim III in 1807, the European Revolutions of 1848, the Young Turk Revolution in 1910, and the Russian Revolution in 1917. Wars and revolutions now, just as in the past, have much to do with wheat. That is the topic of this book.

Taking off from Budapest on an antique commuter plane, a dozen Hungarian tourists and I headed south over the Eurasian steppes. Through my window, I could see endless wheat fields laid out below like a massive Tetris game, with interlocking squares and rectangles of land straddling the main highways. The railways and roads that sliced through the black soil followed a straight path southward to the Black Sea. Neither the Russian Revolution nor the Second World War nor the Orange Revolution of the 2000s had erased those sharp grid lines laid down in the nineteenth century.

Ukraine has what may be the richest soil in the world. Called chernozem, it is a dark, beautifully aerated loam that allows worms and bacteria to thrive. In 1768, the tsarina Catherine II sent more than a hundred thousand Russian troops through this region and across the Black Sea to capture it. She had an audacious plan to build the Russian Empire by borrowing food, seizing the steppe, planting wheat here, and then feeding all of Europe. Five thousand miles away, American colonists had a similar plan, and both seemed utterly utopian. Then a revolution in Paris over the price of bread, the rise of Napoleon, and the burning of thousands of wheat fields in Europe changed all that. Odessa became a grain-exporting boomtown and made the tsars who followed Catherine and their landowning nobility rich. Wheat grown in those black rectangles traveled by oxcart to Odessa, where workers loaded the sacks onto Greek-owned ships bound for Livorno, London, and Liverpool to feed European cities at war. Wealth poured into Russias newly built port. In a few decades, French migr architects, refugees from the Revolution, had designed the Vorontsov Palace, along with Alexander Square, the Odessa Opera House, and the majestic summer dachas of southern Russias moneyed estate owners and grain traders. The most beautiful dachas surrounded the imperial botanical gardens.

After Napoleons defeat, these vast fields of Russian wheat did not delight European landlords. They faced what is called Ricardos paradox, in which rents drop when food gets cheap. For forty years taxes on foreign grain slowed cheap sacks of Russian Azima and Ghirka wheat. But then a water mold, unknowingly carried in from America, killed potatoes and brought food insecurity that forced European states to open the trading floodgates to wheat again in 1846. A century-long contest emerged between the wheat fields of Russia and the wheat fields of America to feed Europes working class.