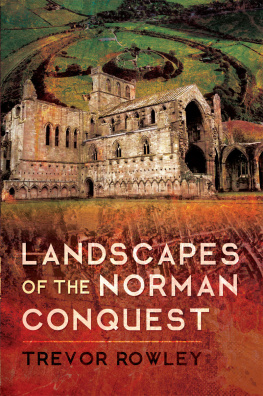

THE WOMEN WHO SAVED THE ENGLISH COUNTRYSIDE

Copyright 2022 Matthew Kelly

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

All reasonable efforts have been made to provide accurate sources for all images that appear in this book. Any discrepancies or omissions will be rectified in future editions.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022930463

e-ISBN 978-0-300-26530-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Chapter opener illustrations by Sarah Young.

Plates

Maps

).

).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the many people who have helped this book come together. To friends and colleagues at Northumbria for their support and inspiration, especially Charlotte Alston, Lilian Armour, David Gleeson, Kay Howell, Daniel Laqua, Tom Lawson, James McConnel, Brian Ward, and the members of our ever-expanding Environmental Humanities Research Group. To Ben Anderson, Jeremy Burchardt, Katrina Navickas, Gale Pettifer, Paul Readman, Linda Ross, Ian Waites, and all the contributors to the Rural Modernism, Decommissioning the Twentieth Century, and Changing Landscapes, Changing Lives projects, from whom I learn so much. To my PhD students Louis Holland Bonnet, Ciaran Johnson, and Nick Pepper, for keeping the day job so exciting and rewarding. To Dagmar Schfer, Director of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, and Wilko Graf von Hardenberg: I wish other pressures had allowed me to take up a longer fellowship. To Clare Alexander, my inestimable agent, to Julian Loose, for his faith and editorial direction, and to all at Yale, from the marketing team to Frazer Martin and Lucy Buchan, who patiently kept me on track as the book went into production. To Neil Gower, for the charming yet clever cover, to Sarah Young for the lovely chapter openers, to Jenny Roberts, a peerless copyeditor who mostly managed to save me from myself, and to Amanda Speake for the meticulous index. To Bethany Hamblen at Balliol and Alexandra Healey at Newcastle for giving so generously of their time and enabling access to archival material during the Covid-19 lockdown. To the National Trust for allowing me to quote from the Octavia Hill and Beatrix Potter letters. To Robin and Frances Dower, without whose kindness and generosity this book would have been so much less, and to Kate Ashbrook, who talked with me about Sylvia Sayer, shared images, and deserves her own chapter. To Martin Conway, Roy and Aisling Foster, Ultn Gillen, Neil Gregor, Leonie Hicks, Ian McBride, James McConnel, Caoimhe Nic Dhibhid, Colin Reid, Katie Ritson, and William Whyte for their long service in the field. Special thanks to Josie McLellan, the most astute and energising of confidantes these past 25 years. And, finally, to Katarzyna Kosior, to whom this book is dedicated. She lived this project for as long as I did, enduring months of lockdown and online teaching, and yet still brings such joy to all we do together.

MK, Tynedale

January 2022

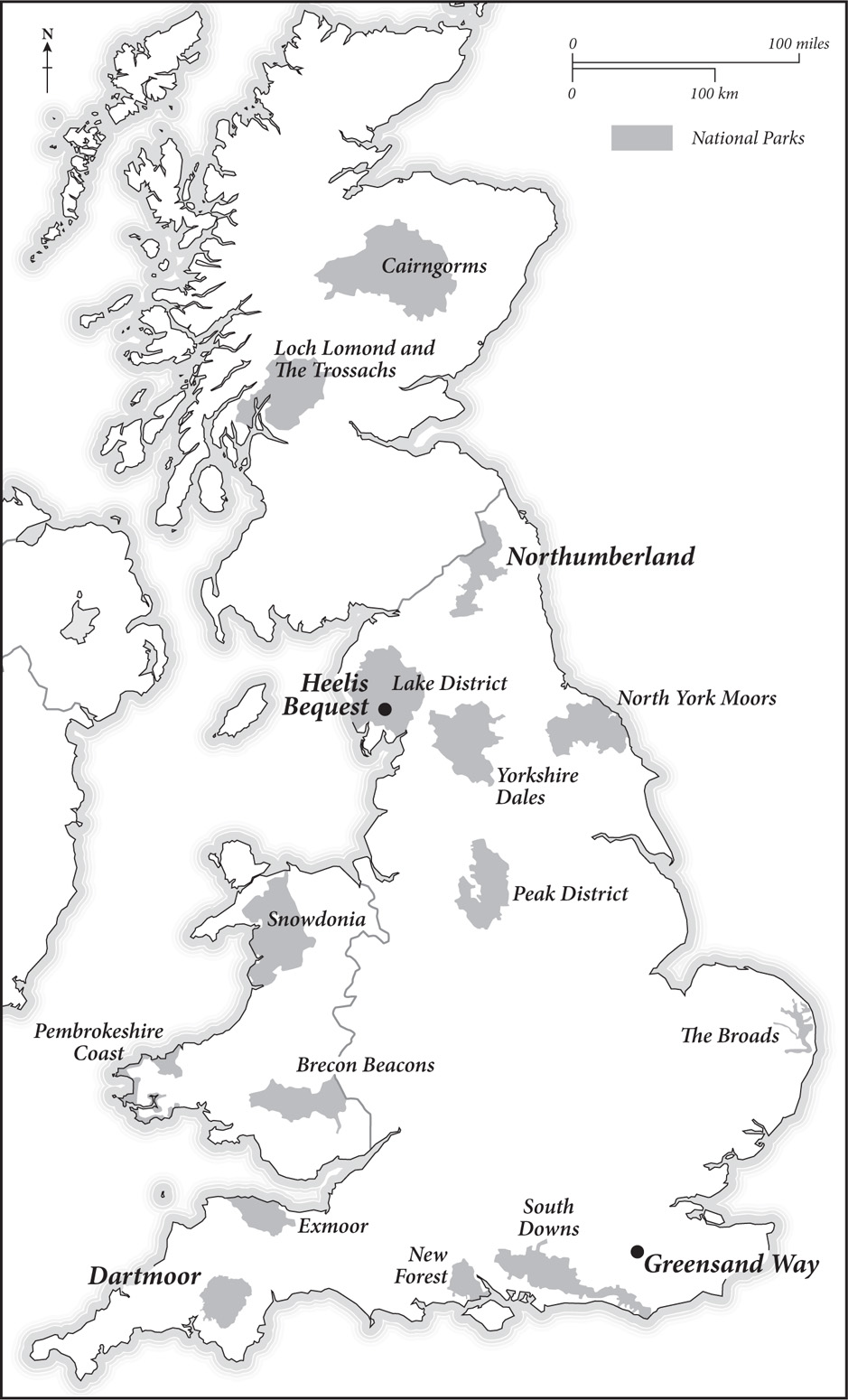

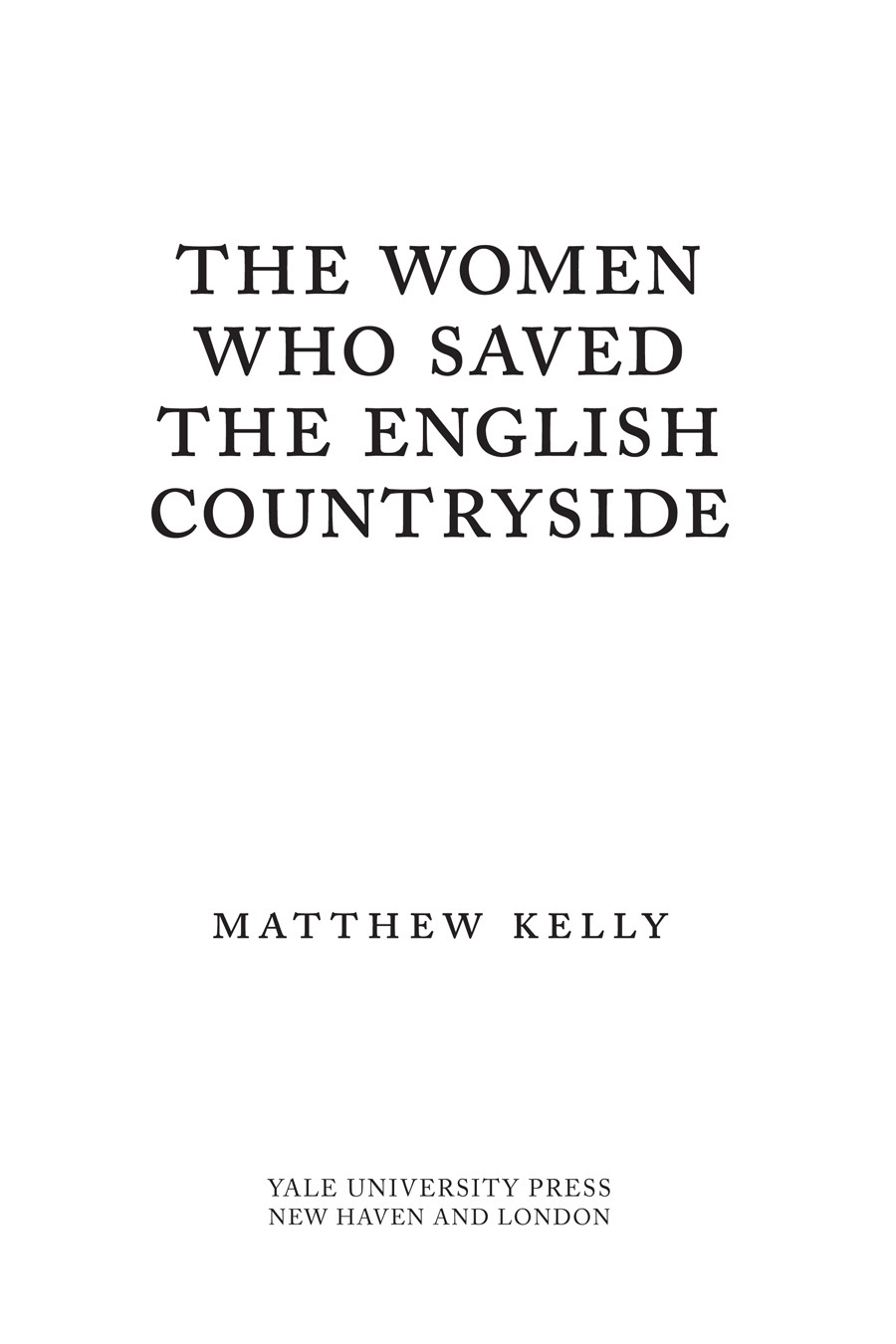

Britains National Park system and key locations examined in this book.

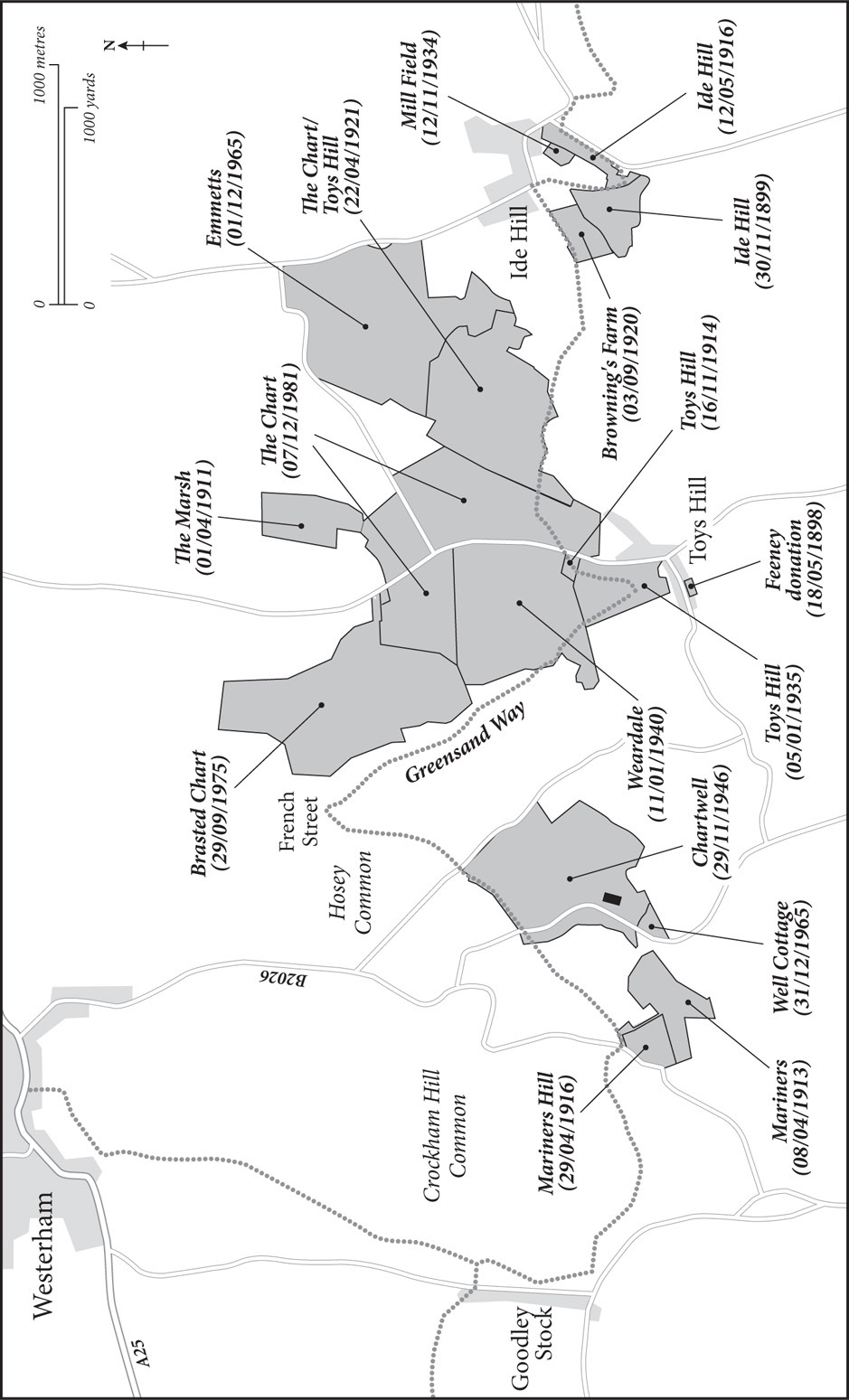

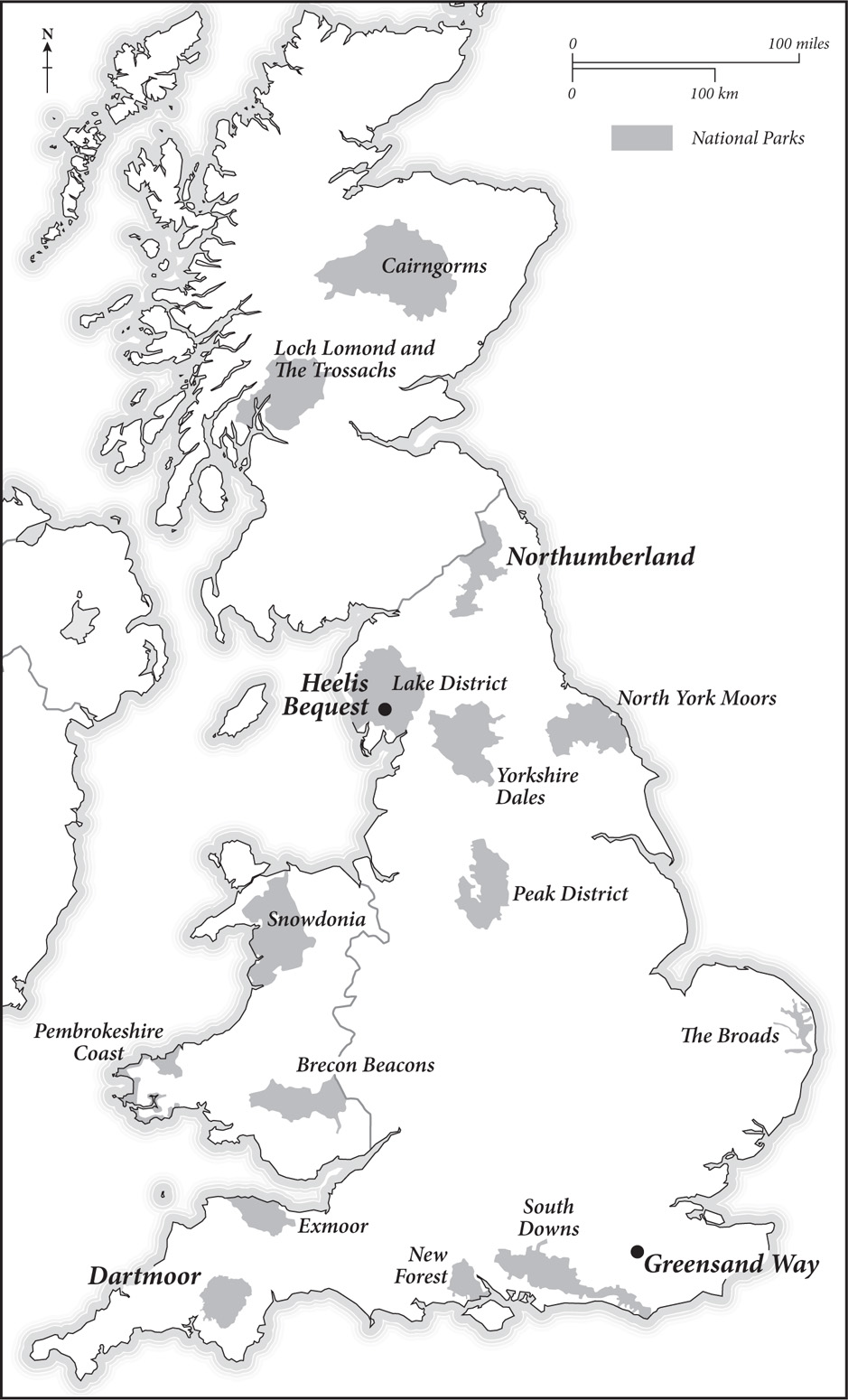

National Trust acquisitions along a section of the Greensand Way in Kent.

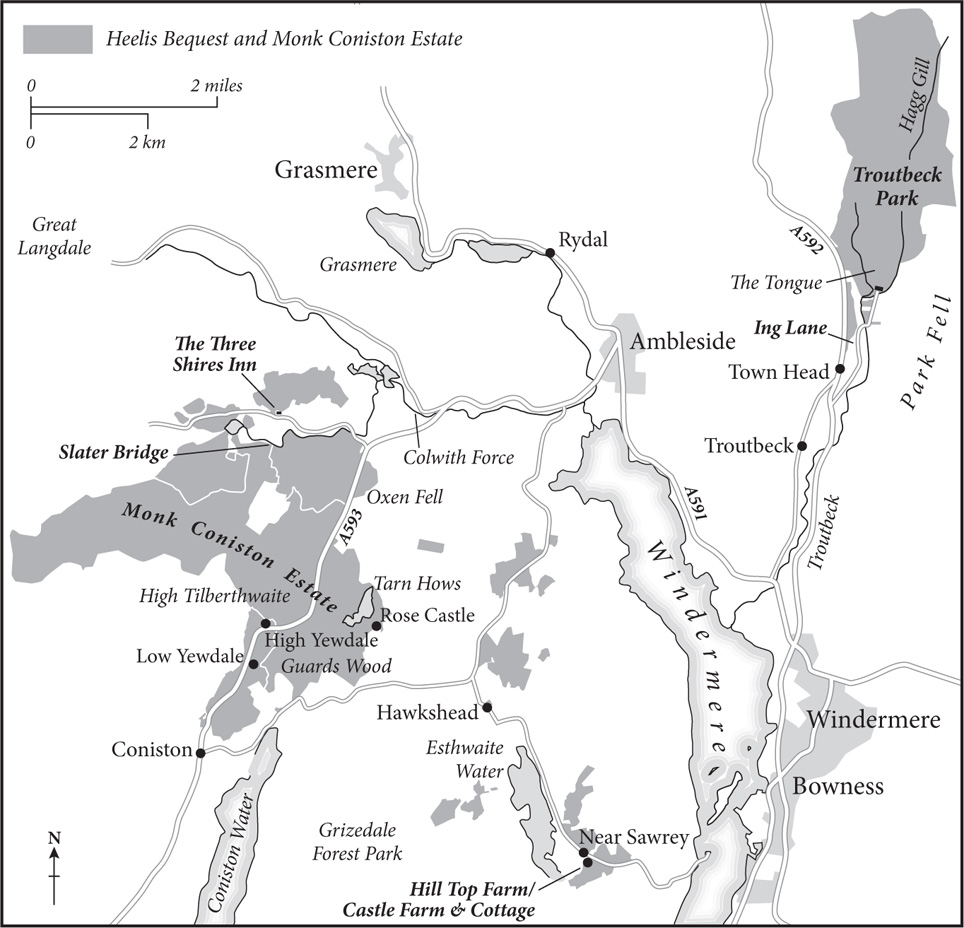

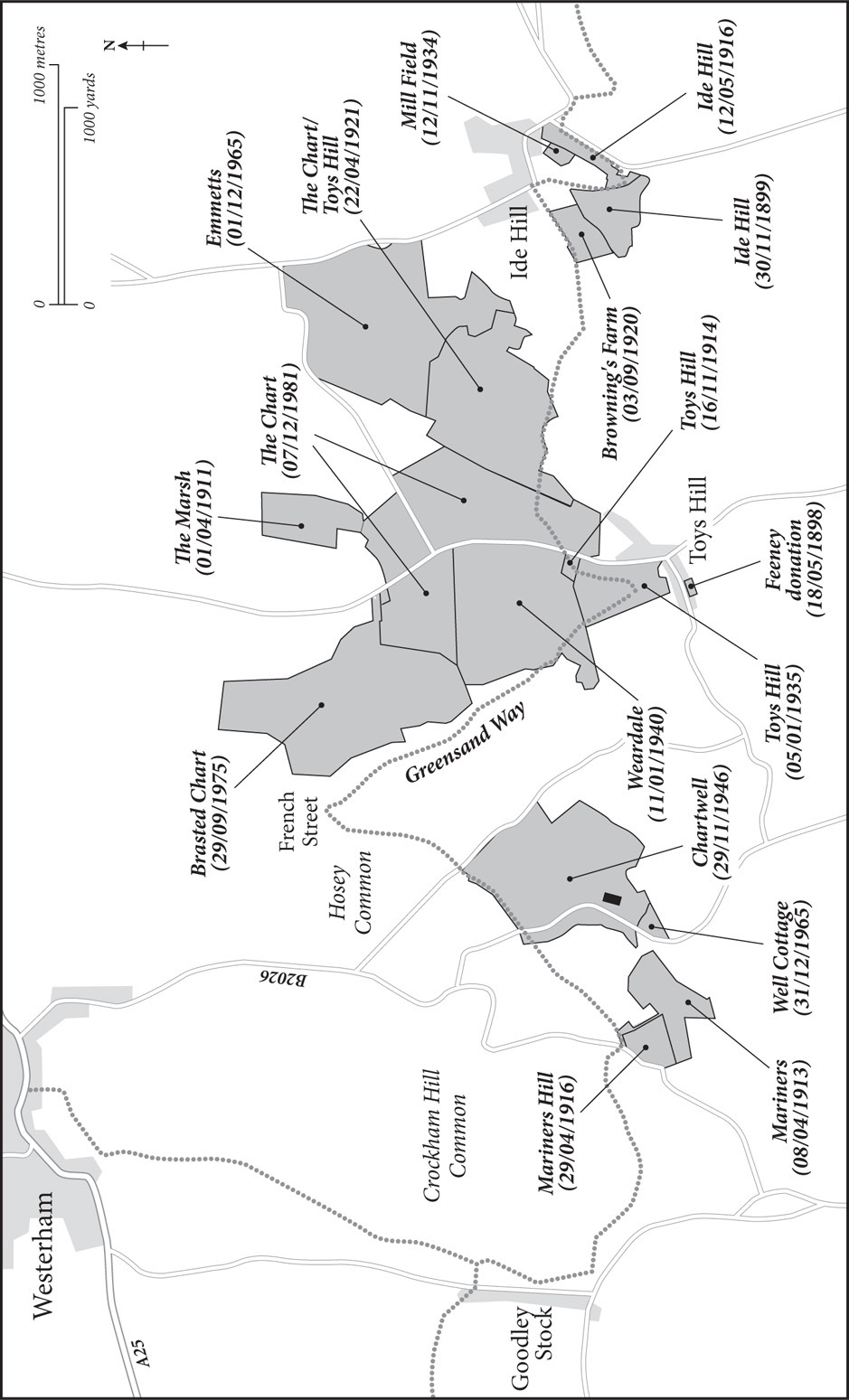

Map showing much of the land Beatrix Potter bequeathed to the National Trust or purchased on its behalf.

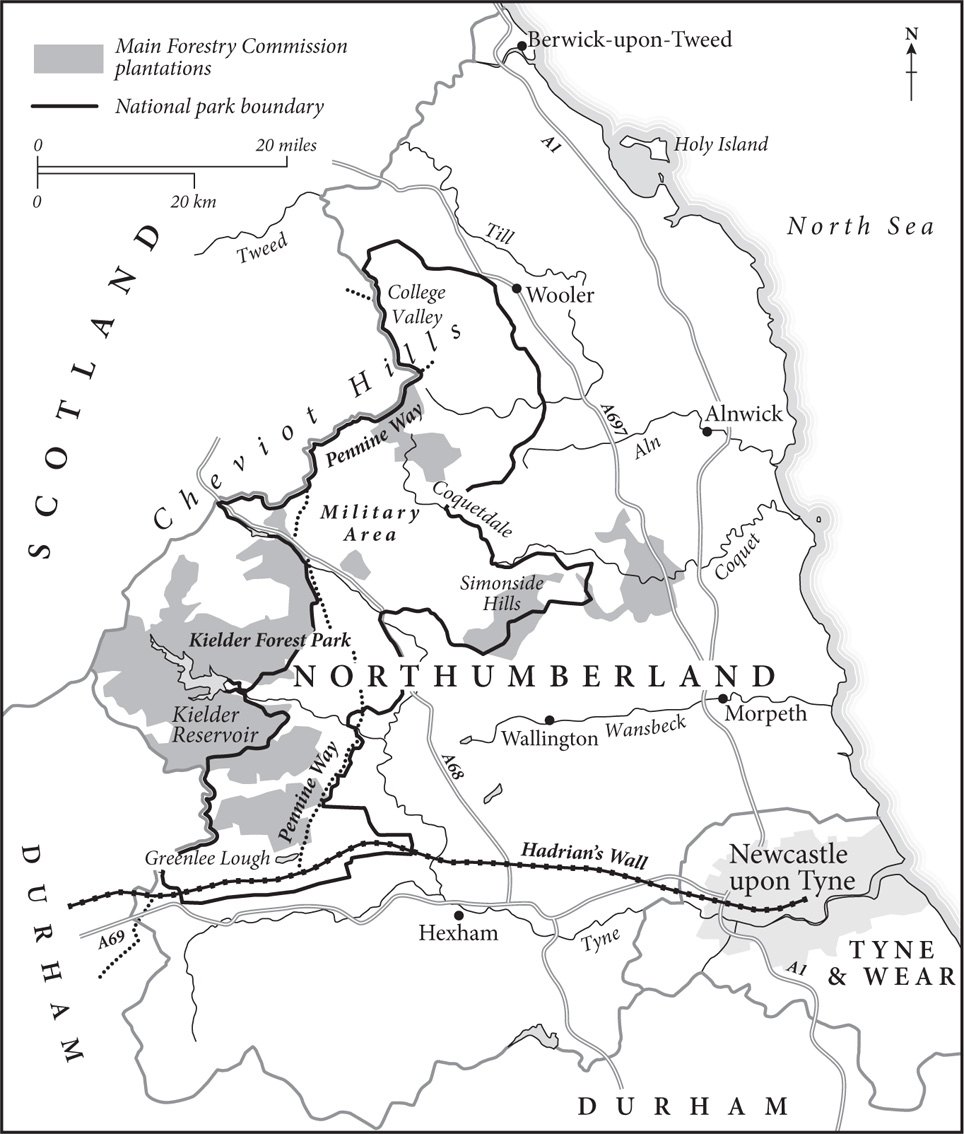

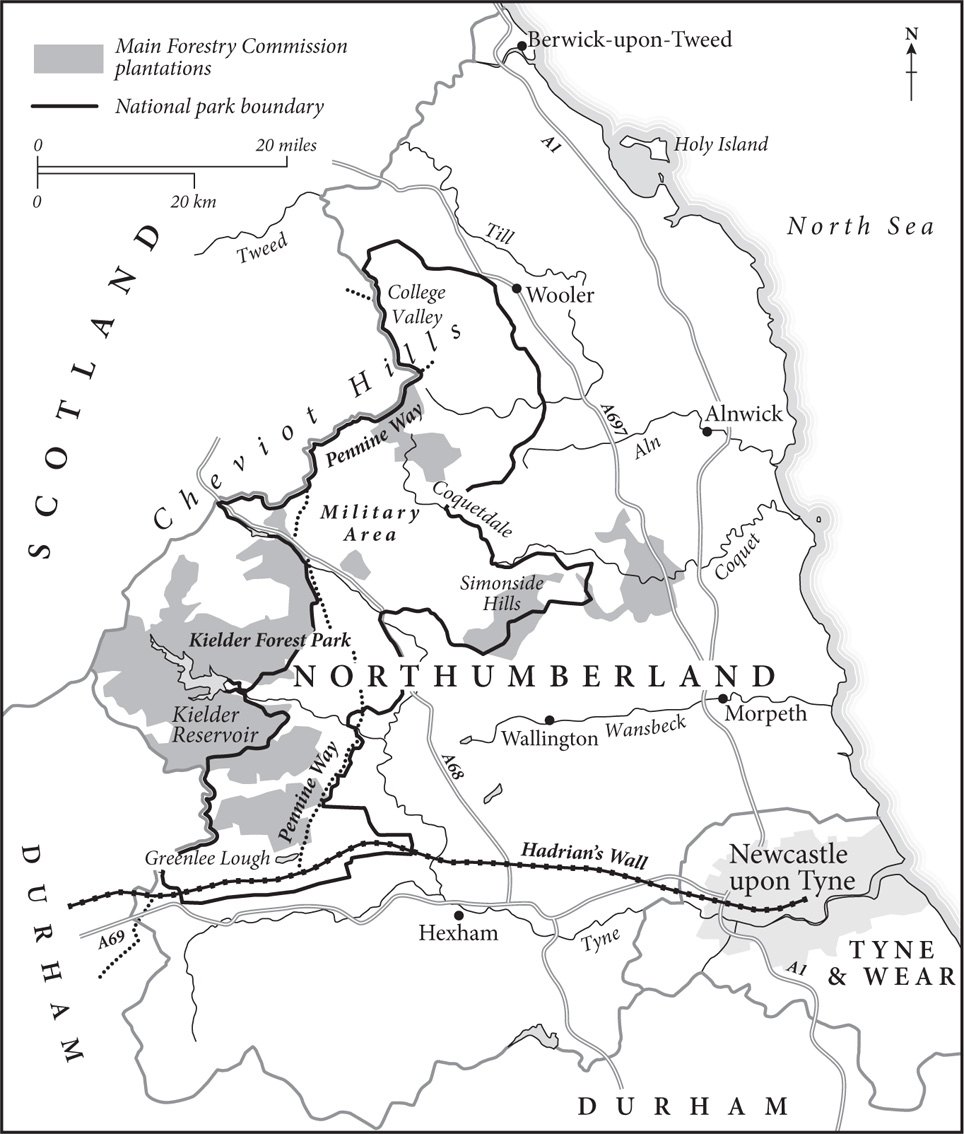

Map of Northumberland showing the boundaries of Northumberland National Park and other key locations mentioned in the text.

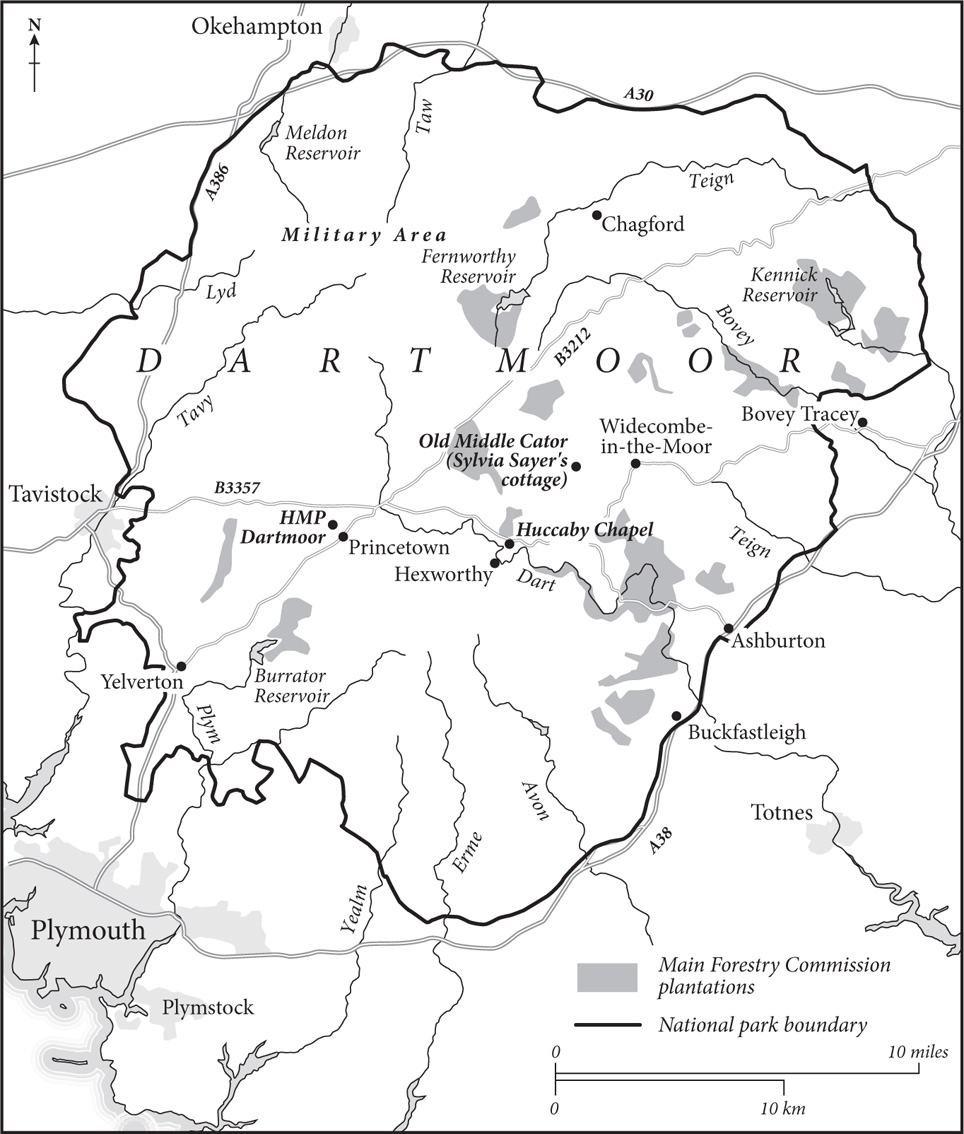

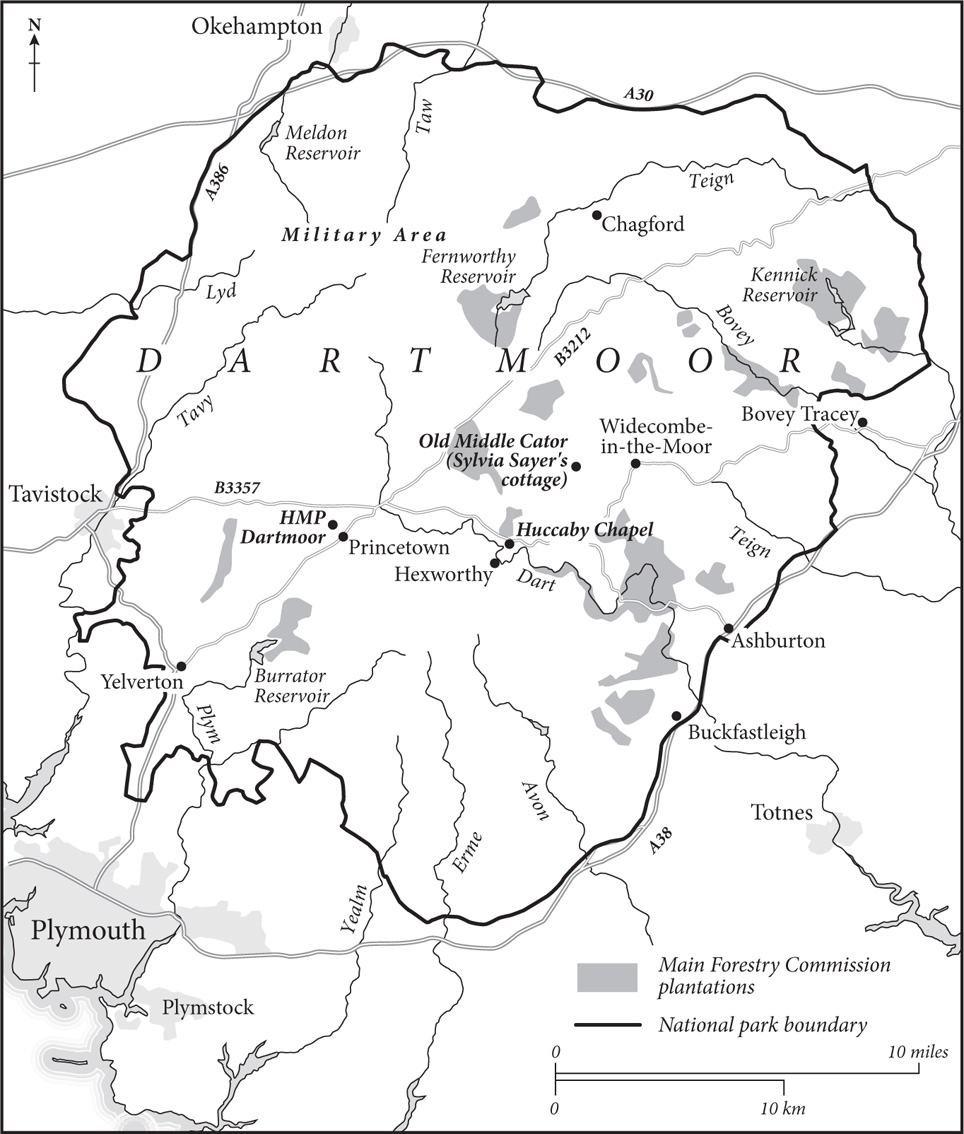

Map showing the boundaries of Dartmoor National Park and some of the key locations associated with Sylvia Sayer and her activism.

Introduction

The Four

O n 22 February 1967, the front page of The Times was dominated by an image of a woman taking a photograph of a helicopter winching an artillery piece. An apparently unconcerned soldier stands in the background; bleak, open moorland recedes towards the distant horizon. This was Ringmoor Down on Dartmoor. The noise and menace of the military helicopter contrasts with the poise and composure of the civilian woman. First published in the Western Morning News, the photograph later migrated to the annual report of the Countryside Commission.

The Times captioned the photograph Woman on the warpath at Dartmoor, but its subject was not an anonymous individual captured by an enterprising press photographer. This was a photo op, likely staged, but no less affective for that. The woman was Sylvia Sayer. That day, she exercised her right to access common land in protest at the use of Dartmoor National Park by the Ministry of Defence as a training ground. Her action highlighted how the military did not have the authority to prevent her from walking across the down. Ordinary people, she insisted, should not be inhibited from exercising their rights by the militarys intrusive and intimidating presence. Sayers attention-seeking action, entirely peaceful, was typical of her long tenure as chair of the Dartmoor Preservation Association. An ardent proponent of national park principles, she believed the militarys use of the parks should be subject to closer controls. Ideally, it should be expelled altogether. Only then could the qualities of the landscape be preserved from further harm and public rights of access guaranteed. This was but one apparently harmful use of the moors that exercised this most determined of campaigners.

By the early 1960s, Sayer was familiar to government ministers and Whitehall civil servants. Regular appearances at contentious planning inquiries and in the letter pages of the broadsheet newspapers had made her a figure of note. Her lucid, hand-written letters, sometimes accompanied by photographs evidencing her complaints, could not be ignored. She was equally the bane of senior army officers, Forestry Commission officials and water authority managers. Their every move on Dartmoor was subject to her scrutiny. If she opposed their plans, and she frequently did, she knew how to deploy the tools at her disposal to disrupt their smooth implementation. Equally, she could align her work with the priorities of the national park authorities, national or regional, chivvying them along, but she readily expressed her displeasure when they failed to live up to their purposes, as she thought they frequently did. From her stone cottage in a tiny Dartmoor hamlet, she orchestrated numerous campaigns that combined her verbal eloquence, combativeness and grasp of legal statute and planning processes, placing her among the most effective post-war environmental campaigners and lobbyists.

Next page