Contents

Guide

Page List

Contents

ancient history

out and about

the watery world

geography

using and abusing nature

extreme earth

the planet in peril

the final frontier

foreword

by Chris Packham

I remember the joy of being able to sit in the front of our Ford Anglia, I remember the red leatherette cover and the weight of the book on my lap and running my fingers around the gold-embossed letters that read Road Atlas of Great Britain. I was The Navigator, like Henry the Navigator, like Magellan, Drake, or Frobisher, like a navigator in a Lancaster bomber. I had the very serious responsibility of getting the Packham family from A to B and back using the best, most efficient route. I studied the key, the scale, and the complex matrix of features and memorized all the symbols because I was not allowed to fail. Our lives, or at least the peace and cordiality in our lives, depended upon me and my maps.

You see, my dad didnt get lost. That was unthinkable, impossible, so I couldnt let him get lost on the tarmac ribbons of England, Scotland, or Wales. But there were two things I didnt yet realize in 1967: One, my dad knew exactly where he was going irrespective of my critical deliberations and directions, because he had all the maps in his head already; and two, I would soon manifest the uncanny ability to go somewhere once, anywhere in the world, and then go straight back there without deviation or hesitation, whether I was sitting in the front and paying attention, or walking or cycling, basically connecting with my surroundings. That is surely down to the way my Aspergers mind works with visual information, but probably also down to this formative training in transcribing it into a geo/topographical context using the template of drawn maps. Because I loved maps, I loved memorizing maps, imagining maps, drawing my own maps of imaginary places. Most of all, I loved the Atlas.

The Atlas was the world on paper, the whole wide world spread over pages, spread out on my tiny bedroom floor. I was here, the jungles of the Congo were there, the altiplano was over there, the desolate outback was on . Thats where the gorillas were, the vicuas were, and the Tasmanian tiger might still be. I looked at the map and saw the spaces and places where all the denizens of my animal encyclopedias roamed, and that gave me something I needed: context.

We now live in an age of information. Many people have forsaken knowledge because they can instantly access information. They dont memorize maps because they have satellite navigation, they dont remember facts because they can find them in seconds if they need to. But without knowing things, there is no ability to build context, the structure that links facts together and explains how they coexist, how they relate and lead to one another, because nothing exists in isolationeven on maps of the outback there is no road to nowhere. Like facts, all roads lead somewhere. I would say they go via knowledge to wisdom.

So as much as I will use satellite navigationits certainly safer than driving with an atlas balanced on your kneesI dont want to permanently rely on such technology because it will ultimately shrink my world. I like technology to expand the world I know, and when it comes to the study of the environment and the natural world, contemporary technology means we are learning a lot more and a lot more quickly than ever before. And that is irrepressibly exciting. But, and its a sad but, we are discovering all these things when so many of the things we are discovering things about are disappearing. So our new knowledge needs to be rapidly, efficiently, and clearly transcribed into a communicable form, so it can be known and shared more widely. In short, this information needs to be made beautiful, and one way of achieving that is through the universal language of maps.

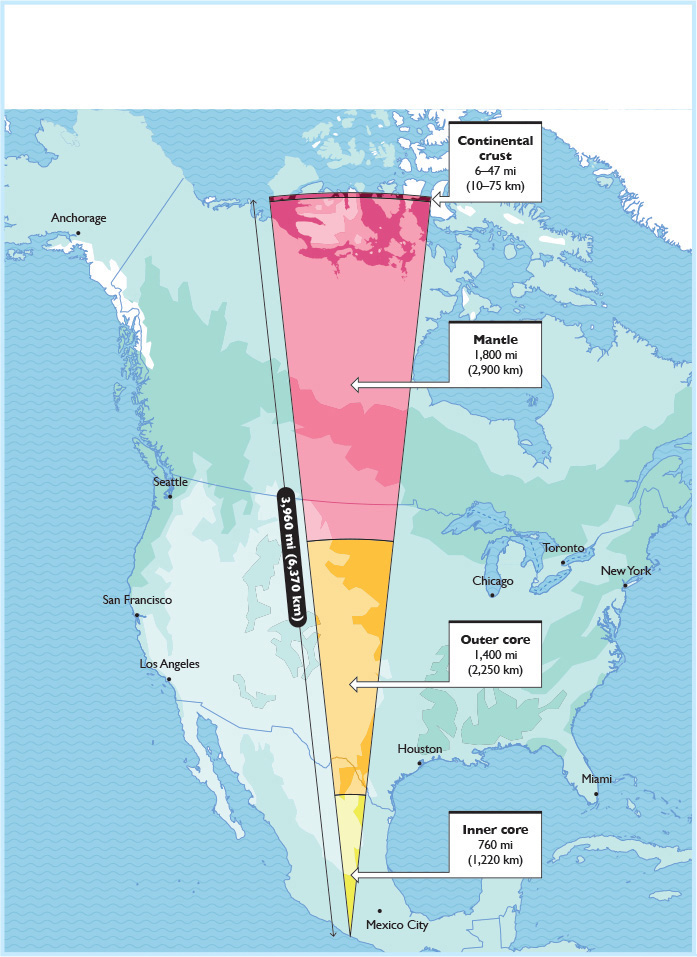

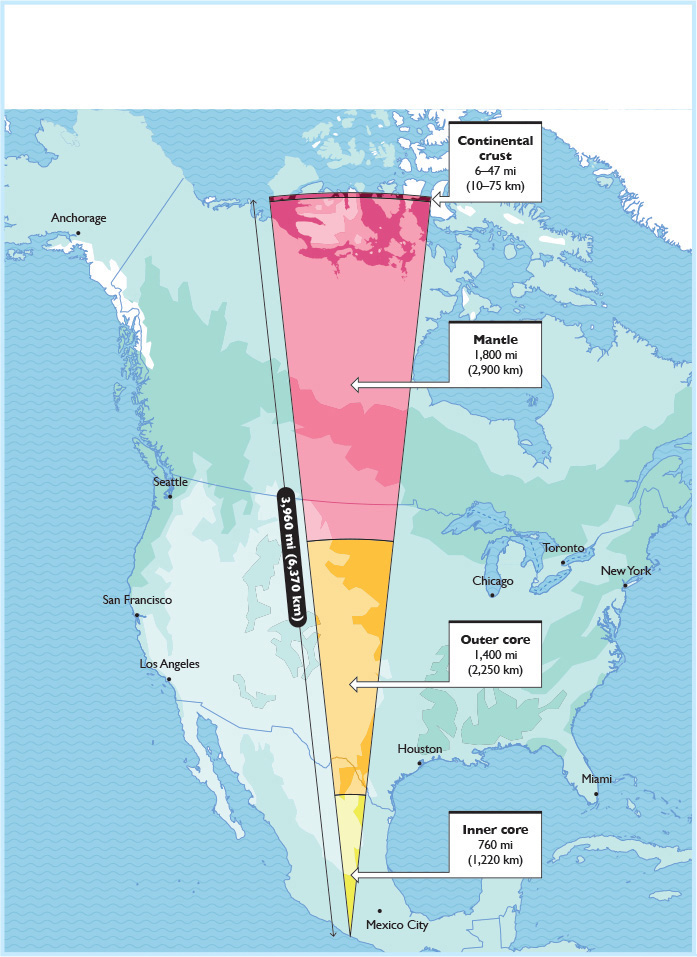

How deep is the Earth?

The maps in this book illustrate a very broad range of facts, but they fall into three or four main categories. Many are interesting: The How deep is the Earth? map () show some real solutions to our problems.

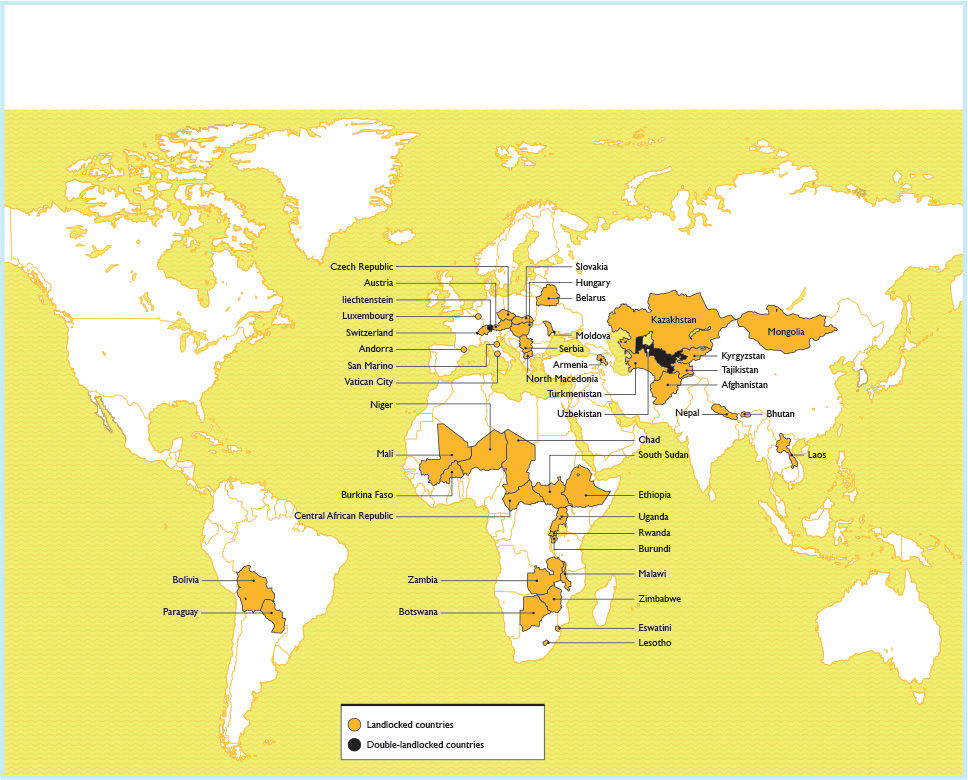

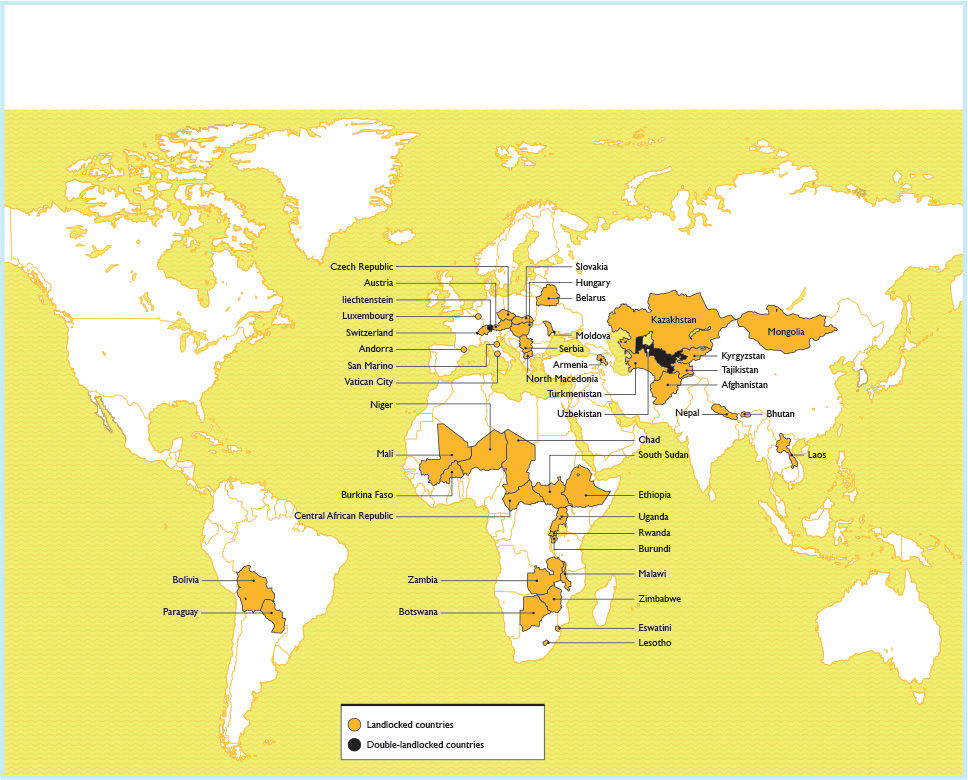

The nations with no sea view

If I had the tough job of picking a favorite it would be the The nations with no sea view (), because its the sort of thing my dad and I would have loved learning on those journeys in the long-gone Ford Anglia. Knowledge, you just cant beat it.

Chris Packham is one of the UKs top television naturalists and an award-winning conservationist, photographer, and author.

Introduction

W e often hear that we live in a globalized world. Perhaps thats why we increasingly turn to maps of the world to better understand the planet and its occupants. Ian Wrights Brilliant Maps for Curious Minds, as well as Matthew Bucklan and Victor Cizeks North American Maps for Curious Mindsthe predecessors to Wild Maps in this seriesdelightfully showed that there was little that couldnt be presented in map form. You might not have thought you needed to know which country has produced the most Miss World winners or where the planets heavy metal bands are concentrated, but its pleasing that someone else did and created those maps (India and Finland, respectively, by the wayand there are 198 other equally intriguing maps in the Maps for Curious Minds series, so do take a look if you havent already). Both previous books in this series had chapters called Nature (my favorite nature map: Countries with no rivers). Those chapters offered the obvious starting point for Wild Maps for Curious Minds, showing us new ways to see the natural worldand how the human race is part of it, for better or worse.

So began the happy search for the 100 maps of this book, strikingly illustrated by Manuel Bortoletti. Some we created ourselves, but many existed already, made by academics, bloggers, professional mapmakers, researchers, campaigners, and institutions. The process of contacting the original creators of these maps was one of the joys of making this book. A community of generous and talented mapmakers out there was willing to grant Manuel and me the opportunity to re-present their work here. John Nelson (Imagine all the oceans as a single body of water; ) are deceptively simple, but built on the expertise of the HydroSHEDS and HydroLAKES projects.

The increasing availability of powerful and affordable digital mapping technology has led to a boom in interactive online tools that helped us create at least two maps: Sam Learners wonderful website River Runner is behind The tiny creek that connects the Atlantic and Pacific () a bit trickier without Chris Yangs interactive creation, Countries Mapped onto Solar System Bodies.